AEI-Insights - AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ASIA-EUROPE RELATIONS

(ISSN: 2289-800X); JANUARY, 2017; Volume 3, Number 1

Andreas Stoffers1+ and Benno Fuchs2

University of Applied Languages / SDI Munich, Germany

1andreas.stoffers@sdi-muenchen.de; 2fuchs.sdi@web.de

+Corresponding Author

With its enormous economic growth rate of an average 6% p.a. over the last 15 years, ASEAN has emerged to be one of the most vibrant and promising regions in the world. Long before the inauguration of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) in 2015, the European Union’s economy in general and Germany’s in particular, has realized the potential of Southeast Asia as an outlet, trading partner, and production base. Besides bilateral relations, regional economic zones like ASEAN, EU and NAFTA as well as multinational agreements like TPP and TTIP are gaining ground. At the same time, the hunger for energy is rising in line with the economic boom, even exceeding the latter rates. In order to meet the rising demand ASEAN will be increasingly focused on sustainable energy. In this article, the opportunities for sustainable energy supply in ASEAN are assessed, based on the example of Germany and Vietnam and the background of global and regional economic integration. Due to the limited space in this article, the authors focus on the positive aspects of the German-Vietnamese cooperation being well aware that there are also other bilateral relationships worthwhile to investigate. Furthermore, there is the need to have in mind that there are also pitfalls and alternatives, which needs to be discussed in a follow-up article.

Keywords

ASEAN, EU, Globalization, Bilateral Cooperation, Energy Efficiency, Sustainable Development, Green Building, Photovoltaic, Renewable Energy, Bio Mass, FTA, FDI, German-Vietnamese Relations

“In the 21st century global economy, the United States’ prosperity is directly tied to our ability to sell American goods and services to the 95% of consumers who live beyond our borders”, wrote Penny Pritzker, commenting on the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) in April 2016(Trans-Pacific Partnership Opportunities by Markets, 2016). Pritzker is not alone with this statement. The TPP, which was signed recently, comprises 12 Pacific Rim countries (Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, Vietnam and the USA). It will account for 40% of global GDP and is expected to have a major effect on the global economy. TPP’s impact is even bigger as the member countries are also involved in other economic blocs like ASEAN (Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam) or NAFTA (Canada, Mexico, USA) or MERCOSUR (as associated countries: Chile, Japan, Peru), which partly follow the principles of free trade. Moreover, other FTAs exist between TPP-members and other countries and blocs (e.g. Vietnam-EU FTA, signed in 2015, but not yet ratified), or between the latter economic blocs and other countries (e.g. ASEAN and China, South Korea and India). This variety of FTA in the APEC region is commonly referred to as “noodle bowl” of arrangements with numerous, partly overlapping agreements, which is on the one hand increasing the complexity to do business in the region, on the other hand an opportunity to match the interests of nations bilaterally (Dent, 2016) .

As far as the North Atlantic is concerned, the TTIP is still in the making, in spite of some severe resistance from European groups and citizens as well as from US-American circles, including the 2017 Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump. Negotiations are difficult and it is still not sure, whether an acceptable agreement will be possible at all. Regardless of setbacks such as the Asian Crisis in 1997, the Financial Crisis in the late 2000s or the EU Crisis along with the persisting problems in Greece and the Brexit, the thrift towards liberalization and FTAs is gaining ground in a globalized and well-connected world.

After the failure of Bretton Woods in 1971 and the end of the convertibility of the US dollar to gold, it seemed for many years that the idea of liberalism and free trade was losing ground. In fact, the efforts to continue building a world based on free exchange of goods and services never lost momentum. However, the effort to reach a worldwide agreement along with WTO (since 1995) or GATT (1947-1994) proved to be unsuccessful, as it was too difficult to define generally accepted rules for all nations. Bilateral agreements (e.g. EU-Singapore FTA) and regional cooperative efforts (e.g. ASEAN Economic Community AEC 2015) stood for new approaches in global trade. And – in many aspects – they proved to be successful. Moreover, new players have entered the stage. Besides the existing economic blocs and international organizations like IMF and the World Bank, China is demanding a more decisive role in international business. The China-dominated Asia Infrastructure and Investment Bank AIIB, which was founded in 2014/2015, is part of the “new-world order”, as China understands it(McDowel, 2015). (AIIB).

FTA, economic blocs, international institutions and development banks are part of the new cosmos of global business and trade. Economic survival in the globalized world depends on facing new challenges and acting cautiously in an environment based on tactical and careful negotiations on the one hand and each national economy’s orientation toward international competition and global markets on the other hand. In line with the growing number of FTAs, tariffs and quota will lose their relevance. But technical barriers, incentives for local producers, and non-tariff-barriers still remain a source of limitation to free trade. This will make detailed and careful negotiations, clarifications and agreements, a factor for success.

For many companies, ASEAN is an attractive trading partner and FDI destination. Founded on 8th August 1967 in Bangkok with the signing of the “Bangkok Declaration”, ASEAN was a “child of the Cold War” at first. It was initially meant to stabilize and safeguard the connectivity of the anti-communist countries Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand in order to contain the expansion of communism. Brunei was the next to join on 7th January 1984. The Membership of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (28th July 1995) was the visible sign that the initial political target had turned into a close regional cooperation beyond ideology as the Cold War was over. In the subsequent years, Laos, Myanmar (both on 23rd July 1997) and Cambodia (on 30th April 1999) joined, making up the current ten members of ASEAN as it is today.

Based on mutual respect for the independence, sovereignty, equality, territorial integrity, and national identity of all nations, the 10 ASEAN nations agreed in 1997 on “The ASEAN Vision 2020” as a shared vision of ASEAN’s future. Sixteen years later, at the 9th ASEAN Summit in 2003, the ASEAN leaders committed themselves to the goal to establish the ASEAN Community. In the Cebu Declaration, which was inked at the 12th ASEAN Summit in January 2007, the target was set to finally establish the ASEAN Community by 2015. To do so, the three pillars of the ASEAN Community were defined:

In terms of economic cooperation and from an European perspective, AEC 2015 is the most interesting pillar since it will create a stable, prosperous, and highly competitive ASEAN economic region by 2020 based on, free flow of goods, services and investment; improved flow of capital; equitable economic development and last, but not least reduced poverty and socio-economic disparities. (asean.org/asean, asean.org/wp-content, asean.org/…Aug_2015, asean.org/…262)

EU investors who wish to do business in ASEAN can enter a single market rather than dealing with 10 stand-alone and fragmented economies. They gain access to more than 600 million prospective consumers and can establish a single production base in order to, tap on product and services complementation in the region, establish a network of industries across ASEAN and participate in the global supply chain. On the other hand, ASEAN-based EU companies get access to raw materials, production inputs and services, labour, and capital wherever in ASEAN they choose to set-up their operations. These EU companies can save production costs, focus on their specialization, and maximize economies of scale, without missing out on markets with high potential. For example retail companies, such as supermarkets, can offer the market a wider range of products. Exporters in ASEAN, such as furniture and jewellery makers, can diversify their markets and manage business risks. SMEs in supporting industries can more easily integrate themselves into the regional supply chain and global economy. Large multinationals doing business in ASEAN have wider options in selecting regional hubs and marketing offices.

An additional positive effect for EU trade and investment in ASEAN is the growing number of FTAs between ASEAN or single ASEAN member states and the “world outside” (see Table 1). This improves the connectivity of the Asia-Pacific region and the attractiveness for FDI. For instance, the FTA between China and ASEAN is useful as it allows entering the Chinese market from a production base in ASEAN.

Table 1: FTAs in and with ASEAN

| ASEAN Country | Number of FTAs | Countries ASEAN has FTAs with |

|---|---|---|

| Brunei | 16 |

|

| Cambodia | 15 | |

| Indonesia | 16 | |

| Laos | 17 | |

| Malaysia | 18 | |

| Myanmar | 15 | |

| Philippines | 16 | |

| Singapore | 26 | |

| Vietnam | 19 | |

| Thailand | 16 |

Source: ASEAN Business Partners GmbH (internal publication: June, 2016)

To put it in a nutshell, ASEAN opens new opportunities for EU companies. On the one hand, AEC 2015 offers many new possibilities, especially when European enterprises decide to open a subsidiary in one of the 10 ASEAN countries. On the other hand, the existing competition between and the hunger for investment of the ASEAN countries also presents an advantage for European investors. A practical example therefore would be, that investors while discussing FDI with the Thai Board of Investment (BOI) they can also mention their appointments with Vietnam’s Ministry of Planning and Investment (MPI) and Malaysia’s Investment Development Authority (MIDA). Competition can therefore serve as lubricant for business activities, for FDI as well as for trade.

However, each investment and trade activity needs careful consideration. Without knowledge of the market and the major players as well as without intercultural management expertise, business activities are doomed to failure. There are legions of misdirected European investment in ASEAN(Matthias Dühn, 2016). Moreover, EU-investors should try to work hand in hand with EU member states authorities (e.g. the local Chambers of Commerce) and the EU in itself (e.g. the European Delegations or EuroCham). As there is much room for improvement, especially regarding bilateral FTAs. Additionally, the artificial barrier between ODA and commercial FTA should be revised on a case-to-case basis, e.g. for investments in renewable energy, where the environment protection agenda of several European governments goes hand in hand with commercial interests of their national companies.

Missing the business opportunity to enter ASEAN and leaving the terrain to Chinese, Korean and Japanese investors could be a similar mistake as it did when not doing business with China in the previous decades. EU is a great supporter of ASEAN cooperation and integration. However, sometimes there is a “mismatch between political ambitions and the capacities, capabilities and often political will of several member states to walk the talk”, as Jörn Dosch of Rostock Universty described the situation in 2013(Dosch, 2013).

Table 2: Why ASEAN? A SWOT-Analysis

Strength

|

Weakness

|

Opportunities

|

Threats

|

Source: ASEAN Business Partners GmbH (internal publication: January, 2016)

In spite of being more than 8.000 km apart, Vietnam and Germany have much in common. As frontline states in the Cold War, both countries were divided for decades. During many years, the reunification was an important goal for both nations, which Vietnam achieved in 1975 and Germany 15 years later. The experience of separation and reunification is deeply rooted in the mind-set of both nations and support mutual understanding(Kapfenberger, 2013). In fact, the first couple of years after the German reunification were challenging for the bilateral relations because many of the 60.000 Vietnamese contract workers in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR) lost their employment. Most of them returned to Vietnam, but some decided to stay in Germany, which became their second home country. Together with the Vietnamese who already lived in West Germany, these “German Vietnamese” account for a population of 120.000 people. The Vietnamese in Germany are remarkably well integrated. According to researchers, on average, Vietnamese pupils in German schools outperform their German classmates ("Lernen geht immer vor," 2015) (dw). And, compared with immigrants from other nations, Vietnamese are – according to the official German Report on Education (Bildungsbericht) - much better. In Vietnam itself, about 100.000 Vietnamese can speak German, a figure that is second to none in ASEAN(2016).

Since the diplomatic relations between Vietnam and Germany have officially come into being on 23 September 1975 the links between the two partners emerged from a low-level relationship based on trade and official development assistance to an intensive, more diversified economic and political liaison. In the past four decades, Germany and Vietnam have signed several agreements in the areas of investment protection, investment promotion, double tax avoidance as well as maritime and aviation cooperation. (OAV 2015) In October 2011, the “Declaration of Hanoi” marked another highlight. During her visit to Vietnam, Chancellor Angela Merkel agreed with Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung on a strategic cooperation between both countries in the areas of political dialogue, trade, development, rule of law, environment protection, culture and education("Hanoier Erklärung," 2011). One essential result of the Declaration was the German House (Deutsches Haus) project in Ho Chi Minh City, wherefore construction started in November 2014(2016). The Deutsches Haus will serve as a beacon for both German culture and businesses, generating positive effects beyond Vietnam’s borders and will be home to German institutions and businesses.

Another significant milestone was the foundation of the Vietnamese-German University. Founded in 2008, the VGU follows German standards of education with a focus on applied sciences. VGU is targeting to combine sound academic education with practical aspects in cooperation with German high tech companies. Based on a campus in Binh Duong, currently more than 1,000 young Vietnamese are studying at VGU. After the end of the first phase of construction in 2019, the number of students is to increase in the second phase to 5,000 (2020). The figures are supposed to grow to 12,000 in the third phase (2030)(2016).

Altogether, there are about 230 German companies in Vietnam. Besides big players like Siemens, Adidas and Bosch, many companies from the German “Mittelstand” (i.e. SME) have identified Vietnam as a destination for their investment. From 1988 to present 236 German investment projects were approved, totalling $1.34bn. More than four-fifths of the investment projects are in manufacturing, software development and telecommunications(2015).

Germany is by far Vietnam’s most important trading partner in Europe. In 2015, the volume of bilateral trade amounted to a total of €10.3bn, an increase of about 12% compared to the previous year. With imports from Vietnam valuing €8bn and – decreasing compared to the previous year – exports to Vietnam of €2.3bn, the trade balance for Vietnam was positive. A further increase is to be expected after the signing of the FTA with the EU. (Bangkok Post; ICAEW 2016, Vietnamnews) The importance of Vietnam for Germany and the EU can be concluded from the fact that – after Singapore (March 2010) and Malaysia (October 2010) – Vietnam is the third ASEAN country which has such an agreement(2016). Or as Marko Walde, Chief Representative of German Chamber of Commerce summarized in an interview with Vietnam Investment Review on 11th July 2016, “Vietnam is a major frontier market in ASEAN for German companies”("Vietnam Investment Review. FDI allured by a huge single market," 2016).

The most important Vietnamese exports to Germany are electronics, textiles, footwear and agricultural products (e.g. coffee and pepper). The main products imported from Germany are machinery and equipment, motor vehicles and chemical industry products. Vietnam aims to develop into an industrialized country by 2020("Vietnam sticks to goal of becoming industrialized country by 2020," 2014). The related need for high-order systems will be reflected in a further increase in demand for machines 'Made in Germany'.

Germany with its strong economy is situated in the heart of Europe. Vietnam is a key country in ASEAN, one of the most promising regions in the world. (Duanemorris, 2015) As mentioned before, last year, both countries celebrated 40 years of diplomatic relations. The cooperation of Vietnamese and Germans can be described as fruitful and based on mutual respect. Besides the traditional German orientation towards the other European nations and the USA, the central European country should use the cordial relations to Vietnam to intensify economic, cultural and academic cooperation with Vietnam.

Not only does Vietnam represent a remarkable retail market of 90m potential consumers with a growing middle class but it also serves as an essential bridgehead for German business to Southeast Asia. With the EU-Vietnamese FTA signed in 2015 (however not yet ratified) Vietnam could use the competitive advantage within ASEAN to intensify its relations to Germany as its biggest trading partner in the EU. Due to the promising development and the strong fundament, the German-Vietnamese relations could serve as a role model for the bilateral and multilateral relations of various countries in the EU and ASEAN.

There are various reasons for the economic success throughout ASEAN, particularly in Vietnam. The economic development goes hand in hand with the demographic development. With a current population of just over 90m, Vietnam represents the third largest nation in ASEAN.

Table 3: ASEAN Population (in million)

| Population | Latest | Reference | Previous |

| Vietnam | 90.73 | 2014 | 89.71 |

| Indonesia | 252.81 | 2014 | 249.86 |

| Thailand | 67.22 | 2014 | 67.01 |

| Singapore | 5.47 | 2014 | 5.4 |

| Philippines | 100.1 | 2014 | 98.8 |

| Myanmar | 53.72 | 2014 | 53.26 |

| Cambodia | 15.4 | 2014 | 15.14 |

| Malaysia | 30.4 | 2014 | 29.95 |

| Laos | 6.89 | 2014 | 6.77 |

| Brunei | 0.42 | 2014 | 0.42 |

Source: IECONOMICS

Taking into account that it is predicted that Vietnam will have 111m inhabitants by 2050 with a continuous economic growth rate of 5%, a corresponding rise in energy consumption of the industry and trade sector is to be expected.

Just a couple of years ago, overall energy consumption in Vietnam was far from where it is today. According to Cattelaens, Limbacher, Reinke, Stegmueller, & Brohm (2015) energy consumption along with the rate of electrification has risen by more than 300% during the last 25 years alone (p.4). In 1976, only 2.5% of Vietnam’s rural population had access to electricity. By 2013, those figures changed dramatically as the electrification rate rose to 98%. Consequently, the behaviour and attitude of the Vietnamese towards access of electricity changed. Back in 1976, the per-capita consumption was only 45kW a year. Meier, Vagliasindi, & Imran (2015) stress that with an average consumption of 1000kW in 2013, each person now uses more than twenty times of energy than 40 years ago. With those changes, the need for energy has seen an annual growth of 9% for the last 30 years (p. 43).

In order to satisfy this rapidly growing hunger for energy, the Vietnamese government pushed for the construction of various types of power generation facilities with massive investments. On a short and medium-term basis, fossil-fuelled plants are a quick and reasonable source of the urgently needed energy.

Due to very limited reserves of fossil fuels, however, Vietnam is forced to change its long-term plans if Hanoi wants to avoid a deficit in the trade balance, as currently coal and crude oil are being exported on a large scale while refined oil products are imported. With reserves as high as 6bn tons of coal and 161m tones of petroleum equalling a capacity of 85 and 10-15 years respectively, the Vietnamese government is forced to make plans towards a less fossil-dependent energy sector(Meier, Vagliasindi, & Imran, 2015, p. 5771).

In order to illustrate goals for the future orientation on the energy market, power plans are released every couple of years. The latest official Vietnam Power Development Plan VII (PDPVII) for 2011-2020 has six major goals:

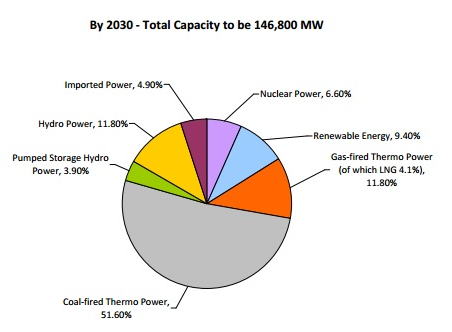

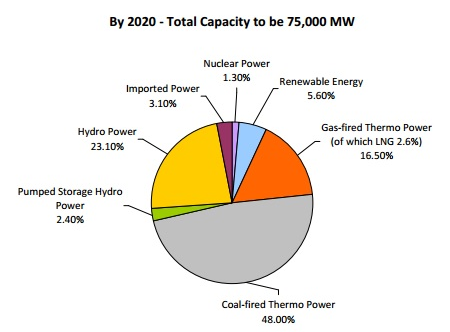

With a distinct focus on renewable energies, the Vietnamese government aims for a lower reliance on fossil fuels and focuses more on environmentally friendly energies. The PDPVII also outlines specific goals concerning the total capacity of each type of energy generation by 2020 and 2030.

Figure 1: Overall capacity by 2020 and 2030 split into the different types of energy generation 1

As figure 1 shows, strong efforts are being made to boost renewable energies. Leaving out hydropower, until recently, “green energies” only accounted for 0.61% of overall energy production. Until 2030, this figure is set to rise to up to 9.40%, resulting in an enormous need for investment in this sector in order to realize the targeted results.

The Vietnamese Power Development Plans, however, have to be seen as a probable direction rather than stated facts, as the Vietnamese Government tend to change the “future orientation” years before the new Power Development Plan would be due. The Revised Power Development Plan, released in 2015 instead of 2020, shows dramatic changes in terms of technologies to be supported. Here Hanoi plans to focus more towards photovoltaics while ignoring wind power nearly completely (GIZ & EAB New Energy).

Sudden changes in the future orientation of the energy market are one vital negative aspect for investors as long-term investments need a certain degree reliability.

The idea of a strong demand not only for financial investments, but also and more importantly know how, offers international companies in the renewable energy sector great opportunities to enter the Vietnamese market. Given the fact that green energies are to represent nearly 10% of Vietnam’s overall energy production in just 14 years and that those technologies are still in the fledgling stages, SME´s as well as large enterprises should take advantage of the current momentum. Internationalizations towards Vietnam are even more attractive than in hardly any other country due to the Vietnamese government´s efforts to offer privileges to companies that feed energy generated by using renewable energies into the Vietnamese power grid in order to attract further investment.

Among other privileges, there are no taxes on imports for goods needed for fixed assets that cannot be produced in Vietnam. There is significantly easier access to reasonable loans and a considerably reduced corporate taxation of up to 100% for the first four years(Tien & Deepak, 2011).

With this given situation, the idea of German investments in the Vietnamese renewable energy sector suggests itself. With 97GW, Germany has the fourth largest installed capacity of installed renewable energy facilities, beaten only by Brazil, the US and China. Comparing the sizes of those countries to Germany, it shows that renewable energies and wind power in particular play an important role in German energy policy. With renewable energies accounting for 29% of overall energy production, the country uses one of the most advanced energy technologies in the world. As energy politics have changed, however, the rate at which green energies have grown during the last couple of years has slowed dramatically, subsequently pushing German companies towards international markets (AG Energiebilanzen).

A prime example of German enterprises in the Vietnamese energy market is Siemens AG. Having already been active on the Vietnamese market for more than two decades, Siemens has developed to become the market leader in combined cycle plants in Vietnam. With high-tech solutions, Siemens delivered for the construction of several power plants in Vietnam and was able to play an important role in the realization of Nhon Trach 2 power plant, which is considered the country’s most efficient power plant. By doing so, Siemens is contributing in a large scale to the solution of the energy production deficit. Furthermore, another major problem in the Vietnamese energy market – the inefficient power transmission throughout the country – could be solved with the implementation of the Siemens SCADA system which would enhance the transmission capacity of the energy grid in 21 provinces and cities in southern Vietnam.

Throughout Germany, strong efforts are made to support companies during their internationalization processes towards ASEAN. As one of the most renowned ODA-consulting agencies, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) [German association for international cooperation] plays, amongst others, a major role in learning and change processes. The GIZ: “supports people in acquiring specialist knowledge, skills and management expertise, […] helps [sic!] organisations, public authorities and private businesses to optimise their organisational, managerial and production processes.” Furthermore, they “advise governments on how to achieve objectives and implement nationwide change processes by incorporating them into legislation and strategies (GIZ, 2016).”

Serving as contact points in all questions regarding internationalization processes, numerous associations and companies other than GIZ contribute greatly to German companies’ successful market entry and further development in Vietnam. These include the Federal Government of Germany, the German Chambers of Industry and Commerce (IHK/AHK) and Bayern International among others.

With eight wind power projects and several further projects in the biomass, hydropower and photovoltaics industry, German contribution to the Vietnamese market is rising annually. Keeping the stated facts in mind, as well as the strong efforts of the German government and the German economy to support internationalization processes, the chances of entering this Southeast Asian market as a pioneer are more promising than ever before.

Along with the irreversible and growing globalization, ASEAN and the EU are both facing new challenges. The “old economies” in the West have to be prepared to face stronger competition in the world, especially from emerging countries like the ASEAN member states, which are hungry for wealth and development. Transnational organizations and FTA are gaining ground. Managing this development successfully is a challenge for all players from business to diplomacy, from NGOs to the individuals. It should be the targeted from all sides to increase mutual perception and understanding. The creation of a multidisciplinary European think tank, especially dealing with ASEAN, could be a good solution to focus the ideas and efforts of the academic sphere connecting it to the existing organizations like the Chamber of Commerce. In Germany, the European Institute for ASEAN studies was founded in 2016. It could serve as one new EU bridgehead to ASEAN (EIFAS 2015).

As far as the energy sector is concerned, Vietnam boasts enormous potential for foreign investors. There is an immense need for know-how and high-tech solutions, which is why Germany and other European countries should focus more intensively on ASEAN and Vietnam in particular.

Investors’ concerns in terms of legal certainty, corruption etc. are legitimate when considering investing in countries that may not yet be considered industrialized countries. However, due to FTA´s, bilateral agreements and the membership of Vietnam in the WTO, AEC etc., risks are slowly but steadily falling away while the chances remain high. Strong efforts are being made by German politics, the economy as well as the academic network to intensify the relations with ASEAN and Vietnam, as the momentum is more promising than ever before. The help offered in various ways for SME´s is paving the way towards a fruitful internationalization. This becomes even more relevant when considering the fact that non-European countries have started to recognize the potential of this aspiring economic area. Nonetheless, investors must be clear on the fact that the Vietnamese Government is perhaps even more influential on its own economy than most European countries. Sudden of unexpected changes in politics can quickly change the environment, even if the rising cooperation with western economies tend to slow down that effect. The current plans show the intention of the government to support FDI with strong efforts; still, even that tendency might possibly change. Those facts, however, could be found in most “non-industrialized” countries, which offer fewer opportunities than ASEAN. In either way, ASEAN is too important for Europe to be overlooked in the 21st – the Pacific – Century, that is why German FDI in the renewable energy sector would be one way to strengthen the cooperation between both economies and to work as a trailblazer for future investments.

1 http://www.greengrowth-elearning.org/pdf/VietNam-GreenGrowth-Strategy.pdf: p.2.

(2015). In A. Stoffers, Deutschlands und Vietnams Perspektiven im Zusammenhang mit der Integration ASEANs und der EU (German and Vietnamese). Hanoi.

ASEAN Business Partners GmbH. (2016). internal publication: January.

ASEAN Business Partners GmbH. (2016). internal publication: June.

Cattelaens, P., Limbacher, E.-L., Reinke, F., Stegmueller, F. F., & Brohm, R. (2015). Overview of the Vietnamese Power Market – a renewable Energy Perspective. Von Deutsche Gesellschaft für international Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) [German association for international cooperation]. abgerufen

Dent, C. M. (2016). East Asian Regionalism (2 Ausg.). London: Routledge.

Department of Commerce, United States of America. (2016). Trans-Pacific Partnership Opportunities by Markets. Washington D.C.

Deutsches Haus Vietnam. (2016). Abgerufen am 30. 10 2016 von http://www.deutscheshausvietnam.com

Die Zeit. (2015). Lernen geht immer vor. Abgerufen am 16. 10 2016 von http://www.zeit.de/2015/24/intelligenz-schule-kinder-familie/komplettansicht

Dosch, J. (June 2013). The ASEAN Economic Community: The Status of Implementation, Challenges and Bottlenecks. Von http://www.cariasean.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Research-Project-Apr-2013.pdf abgerufen

Federal Republic of Germany & Socialist Republic of Vietnam. (2011). Hanoier Erklärung. Von http://www.hanoi.diplo.de/contentblob/3785348/Daten/3472741/Hanoier_Erklaerung.pdf abgerufen

German Embassy Hanoi. (2016). Abgerufen am 30. 10 2016 von http://www.hanoi.diplo.de/Vertretung/hanoi/de/05-Aussenpolitik_20u_20D-VNM_20Bez/05-01_20bilaterale-beziehungen/0-bilaterale-beziehungen.html

GTAI. (2016). Abgerufen am 30. 10 2016 von http://www.gtai.de/GTAI/Navigation/DE/Trade/Maerkte/Wirtschaftsklima/wirtschaftsdaten-kompakt,t=wirtschaftsdaten-kompakt--vietnam,did=1463928.html

IECONOMICS. (kein Datum). Von http://ieconomics.com/population abgerufen

Kapfenberger, H. (2013). Berlin - Bonn - Saigon - Hanoi: Zur geschithe der deutsche-vientamesischen Beziehungen. Berlin.

Matthias Dühn, V. L. (22. 08 2016). (A. Stoffers, Interviewer)

McDowel, D. (2015). New Order: China's Challenge to Global Fincial System (World Poltics Review Features). Brooklyn.

Meier, P., Vagliasindi, M., & Imran, M. (2015). The Design and Sustainability of Renewable Energy Incentives. An Economic Analysis. Abgerufen am 30. 10 2015 von https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/20524/922240PUB0978100Box385358B00PUBLIC0.pdf?sequence=1

Nguyen, K. (2014). Summary of studies on supporting mechanism for development of grid-connected bioenergy power in Vietnam. Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and the Ministry of Industry and Trade of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (MOIT) on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety.

Tien, M. D., & Deepak, S. (2011). Vietnam's energy sector: A review of current energy policies and strategies. Energy Policy, 39(10), 5770–5777.

TuoiTreNews. (2014). Vietnam sticks to goal of becoming industrialized country by 2020. Von http://tuoitrenews.vn/politics/18711/vietnam-sticks-to-goal-of-becoming-industrialized-country-by-2020 abgerufen

VGU University. (2016). Abgerufen am 30. 10 2016 von http://www.vgu.edu.vn/university/

www.vir.com.vn. (2016). Vietnam Investment Review. FDI allured by a huge single market. Von http://www.vir.com.vn/fdi-allured-by-a-huge-single-market.html abgerufen

www.aiib.org

http://asean.org/asean/about-asean/

http://www.asean.org/wp-content/uploads/images/archive/publications/RoadmapASEANCommunity.pdf

http://www.asean.org/storage/2015/09/selected_key_indicators/table1_as_of_Aug_2015.pdf

http://asean.org/storage/2015/09/Table-262.pdf

http://www.bangkokpost.com/learning/advanced/1011793/vietnam-grabs-asean-market-share-in-eu-trade

http://www.bildungsbericht.de/de/bildungsberichte-seit-2006/bildungsbericht-2014/pdf-bildungsbericht-2014/bb-2014.pdfhttp://blogs.duanemorris.com/vietnam/2015/08/17/lawyer-in-vietnam-oliver-massmann-the-most-investor-friendly-country-in-asean/

AG Energiebilanzen (2016). Retrieved 30.10.16 from: http://www.bmwi.de/BMWi/Redaktion/PDF/B/bruttostromerzeugung-in-deutschland,property=pdf, bereich=bmwi2012,sprache=de,rwb=true.pdf

https://country.eiu.com/vietnam

Deutsches Haus Vietnam. Website. Retrieved 30.10.16 from: http://www.deutscheshausvietnam.com

http://www.dw.com/de/erfolgreich-an-deutschen-schulen-vietnamesische-kinder/a-19237644

http://www.eera-ecer.de/ecer-programmes/conference/19/contribution/31739/

EIFAS Website. Retrieved 30.10.16 from: www.eifas.info

GIZ Website Retrieved 30.10.16 from: https://www.giz.de/en/ourservices/270.html

http://www.greengrowth-elearning.org/pdf/VietNam-GreenGrowth-Strategy.pdfGTAI Website Retrieved 30.10.16 from: http://www.gtai.de/GTAI/Navigation/DE/Trade/Maerkte/Wirtschaftsklima/wirtschaftsdaten-kompakt,t=wirtschaftsdaten-kompakt--vietnam,did=1463928.html

Federal Republic of Germany and Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Hanoier Erklärung (2011). Retrieved from: http://www.hanoi.diplo.de/contentblob/3785348/Daten/3472741/Hanoier_Erklaerung.pdf

German Embassy Hanoi. Website. Retrieved 30.10.16 from: http://www.hanoi.diplo.de/Vertretung/hanoi/de/05-Aussenpolitik_20u_20D-VNM_20Bez/05-01_20bilaterale-beziehungen/0-bilaterale-beziehungen.html

http://www.ibtimes.com/southeast-asia-receives-more-foreign-direct-investment-fdi-china-which-now-worlds-1559537

http://www.icaew.com/en/about-icaew/news/press-release-archive/2016-press-releases/icaew-vietnam-will-be-aseans-fastest-growing-economy-in-2016

http://www.icaew.com/~/media/corporate/files/technical/economy/economic%20insight/south%20east%20asia/q2%202016%20sea%20web.ashx

http://ieconomics.com/population

Vietnam Power Development Plan for the 2011-2020 Period (2011).

Retrieved 30.10.2016 from: https://m.mayerbrown.com/Files/Publication/7eb02f45-1783-4f14-8565-bf5120e1ea08/Presentation/PublicationAttachment/5dcbbea1-2d9f-42ae-8cbd-dab97456c4c5/11556.pdf

Meier, Peter; Vagliasindi, Maria; Imran, Mudassar (2015). The Design and Sustainability of Renewable Energy Incentives. An Economic Analysis. Retrieved 30.10.16 from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/20524/922240PUB0978100Box385358B00PUBLIC0.pdf?sequence=1 p.43

http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/economy/the-world-in-2050.html

TuoiTreNews. Vietnam sticks to goal of becoming industrialized country by 2020. Retrieved from: http://tuoitrenews.vn/politics/18711/vietnam-sticks-to-goal-of-becoming-industrialized-country-by-2020

http://vietnamnews.vn/economy/298083/vn-top-productivity-growth-in-asean.html#lC8TqudCuiSoWoXl.97

VGU University Website Retrieved 30.10.16 from: http://www.vgu.edu.vn/university/

Vietnam Investment Review. FDI allured by a huge single market (2016) Retrieved from: http://www.vir.com.vn/fdi-allured-by-a-huge-single-market.html

http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/vietnam

Die Zeit. Lernen geht immer vor (2015). Retrieved 30.10.16 from: http://www.zeit.de/2015/24/intelligenz-schule-kinder-familie/komplettansicht

Last Update: 24/12/2021