AEI-Insights - AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ASIA-EUROPE RELATIONS

(ISSN: 2289-800X); JANUARY, 2016; Volume 2, Number 1

Petr Blizkovskya and Alberto De Gregorio Merinob

aGeneral Secretariat of the Council of the European Union

40-HN-19 175, rue de la Loi - B-1048 Brussels, Belgium

Tel. +32-(0)2-281 51 30

Email: petr.blizkovsky@consilium.europa.eu

bGeneral Secretariat of the Council of the European Union

Office Address: 20-LM-30 175, rue de la Loi - B-1048 Brussels, Belgium

Tel.: +32-(0)2-281 93 53

Email: alberto.degregorio@consilium.europa.eu

The objective of this paper is two-fold: it provides a critical evaluation of integration processes in ASEAN and in The European Union, and it looks at the potential of future cooperation between these two bodies.

The paper offers an analysis of the recent integration efforts in ASEAN and in The European Union. It concludes by suggesting that as a consequence to their respective crises, both regions have recently undergone substantive integration. The economic governance within ASEAN and at ASEAN+3 as well as the legal developments and plan to establish the single market by 2015 will have significant effects. The EU has traversed an integration path by strengthening its economic policy coordination and increasing its economic reform efforts. The Banking Union has also encouragedthe integration history of The EU. Despite the difference in integration methods, both regions continue to evolve into more economically homogenous entities and to promote harmonisation of regulatory and economic governance practices.

Internal development creates new opportunities for both regions to cooperate. Their priorities would include political issues such as peace, anti-terrorism and security issues, a new prosperity agenda (trade, investments, connectivity issues) as well as socio-cultural dialogue. The EU/ASEAN cooperation will likely increase the attractiveness of its regional integration for other parts of the world.

ASEAN, European Union, integration, banking union, bilateral cooperation, multilateralism, economic governance

ASEAN and The European Union constitute two active regions. They both exhibit a track record of economic policy coordination and security-related collective action.

This article considers the development in those regions and attempts to offer perspectives on future possibilities. The past decade has triggered, in both regions, new types of policy coordination. The financial crisis in South East Asia in the late 90’s resulted in more ambitious institutional cooperation among ASEAN Members. Additionally, ASEAN managed to engage partners beyond South East Asia to coordinate their policies in issues such as financial stability, macroeconomic surveillance, security and conflict resolution, and development policy.

The debt crisis of 2008 has also effected change in The EU. The Union evolved towards a genuine economic and monetary body where sovereignty amongst its members, especially within the Euro zone, is mutually shared at a qualitatively new level, compared to the pre-crisis situation. Policy instruments such as The European Stability Mechanism and the creation of The Banking Union has increased the economic-crisis resistance of The European Union more, developments which this paper .

The paper analyses these developments., while presenting that strong regional integration, that occurred in both regions recently, creates a unique momentum between the two partners: both regions are institutionally and politically more deeply integrated than ever before, while concurrently the world faces new global challenges, thus contributing to a compatability between the two regions.

A large body of literature on regionalism in Asia and in Europe exists. Acharya (2009) studies normative foundations for regional cooperation and points out the evolutionary processes involved in the creation of regional norms. Several authors deal with the issues of scope and architecture of regionalism in Asia (Ayson and Taylor, (2009), Tow and Taylor, 2010), who suggest that these issues are not clearly defined. Murray (2010) notes that “Asian policy makers and many scholars tend not to examine formal institutions, while EU specialists regard them as an essential and necessary foundation of the integration processes”.

In the case of EU regionalism, scholars (Gabor, 2014; Bilbao-Ubillos, 2014; Alcidi and Gross, 2014; Hout 2012; Fabbrini, 2013) note the strong normative foundation and clearly defined institutional architecture underpinning the EU integration process, an inter-governmental process, meaning creation of rules, and obligations outside EU treaties, which have been used in the aftermath of the EU sovereign debt crisis.

The ASEAN integration, referred to as an “Asian way” (Acharya 2009) is based on the respect of the sovereignty principle of non-interference and a culture of consensus. Academics assess the regionalisation of ASEAN in two ways. For Dent (2008) ASEAN would evolve into a more rule-based region, while Tay (2009) and others expect to keep the current light institutional framework. For other authors (Morada 2008; and Jetschke 2009) ASEAN will play an even stronger role in regional security and peace.

Academic discussions about the European future institutional architecture are mainly due to the 2008-09 financial crisis and the complicated economic governance that was introduced afterwards. There are however other reasons for such a discussion, those such as the increase of power of the Europe sceptic representatives in the 2014 European Parliament elections, and the possible upcoming UK Referendum about the UK remaining in the EU. Piris (2011) considers a variable geometry as a possible way forward for the EU in this respect.

The analysis below assesses in detail the developments in both regions, and specifically looks at the economic governance.

ASEAN’s track record of policy coordination goes back to 1967. This was based on a voluntary cooperation between its members. This regional grouping began with the initial 5 founding Members (Indonesia, Malaysia, The Philippines, Singapore and Thailand). Consequently, its membership has doubled (Brunei Darussalam, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar and Cambodia). The working method of ASEAN is a political dialogue, and consultation with consensus being the voting rule, if applicable. The region managed well in controlling its security, and registered a spectacular economic growth for many of its members (Yeo 2009 and Yeo 2011).

An important event in ASEAN’s history was the financial crisis of 1997-98, triggered by a quasi-monetary union where several ASEAN members opted for pegging their currency to the US Dollar. This policy measure was combined with a policy of free movement of capital. The financial speculations of “hot money” against financial institutions and sovereign countries like Thailand and Indonesia destabilised several other countries in the region including The Philippines, and Malaysia, as well as countries outside of ASEAN (South Korea and Hong Kong).

The ASEAN financial crisis differed from its European counterpart in economic growth and sound management of member fiscal policies. The reaction of international organisations such as The International Monetary Fund provoked a negative perception in the region, due to inflexibility and “know-how” of the organizations. In these junctures, ASEAN opted to rely more on its own structural strengths, and developed a strategy of ambitious cooperation, creating the ASEAN community and adopting the ASEAN Charter (Hammilton-Hart, 2011).

The ASEAN Charter represents a grounding document equivalent to the Treaties in the European context. The charter entered into force in 2008, presenting ASEAN with a new legal status and institutional architecture. I, while becoming a legally binding instrument for ASEAN Members. The ASEAN community was created in 2007 through the Cebu Declaration and with a deadline of 2015 for achieving its objectives. The ASEAN Community is based on three pillars: political-security, economic, and socio-cultural. The Charter formulated a goal of creating a stable, prosperous and competitive environment, and of establishing a single market within ASEAN by 2015. This would include free movement of goods, harmonised customs, and technical standards. The Charter also stipulates trade liberalisation and close cooperation in the field of energy policy. Institutionally, ASEAN has assumed strong institutional bodies such as the ASEAN summit which provides policy directives and guidelines. Additionally, through the ASEAN Coordinating Council formed by the Foreign Ministers of ASEAN countries as well as The ASEAN Secretariat, ASEAN has become institutionally more robust.

On economic governance, ASEAN adopted frameworks to strengthen its financial stability. It managed to involve key economies from beyond ASEAN to become an integral part. At the first stage, a series of bilateral currency swaps were put in place as of 2002. As of 2010, this ad hoc mechanism evolved into the Chang Mai Initiative of Multilateralism (CMIM). This process-enhanced currency swap mechanism contains 26 central banks and Finance Ministries from ASEAN, and the “+3” countries. Its balance-of-payment recovery ability rises to 120 billion USD every 90 days to 2 years. This mechanism de facto represents a South East Asia IMF type instrument independent from the IMF.

The ASEAN Bond Market Initiative is another framework of the economic governance of ASEAN, aiming at an enhanced bond market of the ASEAN and ASEAN”+3” currencies. It has been operational since 2003 with a renewed mandate from 2008, and is based on voluntary cooperation. It was complemented with the ASEAN+3 Bond Market Forum with an objective to streamline regulatory requirements on the bond market.

Lending operations have been enhanced via creation of credit guarantee and investment facility. Created in 2010, its aim is to reinforce the use of bonds denominated in the currencies of the signatory states, also supporting the market for the private company bonds in the ASEAN+3 countries. Institutionally, it is linked to the Asian Development Bank which has a trust fund with a starting capital of 0.7 billion USD.

The above described instruments of financial solidarity in the ASEAN+3 regions have been complemented by the macro-economic surveillance framework. Two bodies have been established to this end. The ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO) and the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Group (AMRG). The AMRO monitors macroeconomic imbalances, trends and risks, and delivers non-binding recommendations to its ASEAN+3 Members with an objective to maintain financial stability within the region. The Secretariat of AMRO is based in Singapore. The AMRG is a research type group established by the finance ministers, so to follow trade settlements and financial risks in the macro-region.

The economic governance of ASEAN demonstrated the ability of ASEAN to incorporate into its work larger economies in the region such as China, Japan and South Korea. The ASEAN soft method proved to be attractive for other players. In comparison to the European Union and Euro Group, the ASEAN method was extroverted while the EU one was rather introverted. The EU opted for deepening its structures for its single currency. Several of these measures are implemented by not all EU Members, but only those sharing Euro as currency.

Beyond its economic governance, ASEAN also managed to create a broader regional coordination format having ASEAN at its centre. This is a particularly successful strategy accounting for how diversified the region is politically, economically and culturally. ASEAN convenes annual meetings of The East Asia Summit. This includes the Heads of State of The USA, China, Russia, and Australia, and focusses on security and economic stability in the region.

The ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) is another concentric regional grouping which includes the European Union. The ARF focusses on foreign policy and security issues of the South China Sea, progress in which area, the China-ASEAN Code of Conduct of the South China Sea demonstrates.

Finally, ASEAN Members meet with European partners and other delegations within the framework of The Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM). This forum became one of the strategic platforms for discussing macro-regional concerns as well as issues related to globalisation and multilateralism (ASEM, 2013). Its 51 partners include 10 ASEAN Members + 10 non-ASEAN countries of Asia (including Russia, China, India, Japan) as well as The ASEAN Secretariat. On the European side, it includes The EU, its 28 Members, as well as Switzerland and Norway. Other countries such as Kazakhstan and Turkey are now considering whether to request ASEAN Membership.

ASEAN evolved into a successful regional grouping which managed by a soft method to contribute to prosperity and peace in the region. Recently, the ASEAN method has been exported to the broader region, thus promoting ASEAN values beyond the ASEAN region. Internally, after the ASEAN financial crisis, it deepened its economic, political and social cooperation, as well as its institutional structures. These developments, combined, create a reliable and strong partner for another regional grouping, The European Union.

The Euro crisis has prompted the economic integration of The EU and the Euro zone. The solutions provided by the Union and its Member States have shown a principle of the European Union: it is much more difficult to disintegrate than to integrate. Integration has occurred in two major fields: in economic and monetary union (EMU) and in banking union (Clerc, and Grard, 2012; Craig, 2012; de Gregorio Merino, 2012).

On the EMU side, an important degree of integration occurred in order to manage the Treaty divergences between a single currency and the continuation of nation-state-based economic policies. Two measures have been addressed: the establishment of mechanisms of assistance, and reinforcing the economic governance.

The different mechanisms of financial assistance respond to a “law of evolution”, and to an incremental approach rather to a preconceived plan. Each new instrument has been designed in an ever more sophisticated way than the previous one. The first one was agreed to in 2010 granting Greece a pool of bilateral loans of up to 80 billion euro. The second instrument of assistance, The European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) was established as a private company whose shareholders are in the Euro area Member States. Its lending capacity is 440 billion euros and had a limited timeframe. The third assistance instrument, The European Stability Mechanism (ESM), a type of European Monetary Fund, was adopted in 2012. It is a Treaty based intergovernmental and permanent mechanism with a lending capacity is of 700 billion euro.

The second pillar of the new economic and monetary union – the reinforcement of economic governance – has emerged through instruments based on the Treaties, and through intergovernmental instruments.

With respect to economic governance, The EU has adopted several EU law instruments, such as the “six pack” and “two pack” instruments. This strengthens the EU surveillance of draft national budgets before they are adopted. It introduces new pecuniary sanctions for wrongdoer Euro member states, and more so, on a quasi-automatic basis, without political bargaining. New procedures on excessive imbalances (such as real estate or credit bubbles) also emerged.

Governance has been reinforced through instruments agreed outside the framework of The EU Treaties, namely The TSCG. It introduces the balanced budget rule (or the golden rule), governs excessive public deficit and debt, and commits member states to introduce in their national legal orders debt breaks in rules of a constitutional or quasi-constitutional value. Furthermore, it introduces a culture of budgetary rigour into the national constitutional order.

The banking union was another major reform project introduced by The EU after its crisis in 2012-2014. It aims to break the vicious circle between the sovereigns and the troubled banks. It consists of the Single Supervisory Mechanism and the Single Resolution Mechanism. As a result, all of the Euro area (and beyond if agreed by the given Member State) is supervised by The EU and can be subject to a direct recapitalization by The ESM (modalities yet to be agreed). The resolution mechanisms make banks liable in the face of the crisis event (The Bail-in Principle). It also creates a fund for finance by the banking sector itself.

In summary, the EU has evolved significantly after its sovereign debt crisis. It is more integrated, especially through the banking union. Externally, it has become a more reliable partner with economic stability, both to itself and globally. With this development, The EU can now concentrate internally on its growth agenda, and externally to fulfil its active role in international relations.

Building on the individual ASEAN and EU cases, the comparison between the two processes can be done in terms of (a) principles and values (b) institutions and working methods and (c) economic governance. On principles and values, Table 1 provides a summary.

Table 1: ASEAN and EU principles and values compared

| Parameter | Level of Similarity | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Peace, Security, Stability | High | Mentioned in both primary laws |

| Security cooperation | Medium | ASEAN free of nuclear arms/weapons of mass destruction commitment. EU has light security policy |

| Single market | High | ASEAN has lower ambition and lighter method than EU EU single market law-based but still unfinished |

| Economic and social cohesion | High | Objective similar, ASEAN lacking common fund unlike EU. |

| Values | High | Democracy, good governance, rule of law, human rights common for both |

Table 1 suggests that in both cases, the principles upon which the regional cooperation is established is very similar and mutually compatible. This creates a good basis for the strategic partnership of the two regions in international relations.

On institutions and working methods, the situation differ, both in their institutional set-ups and working methods (Table 2).

| Parameter | Level of Similarity | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Existence of founding treaty | Full | Both regions are enjoying their founding treaties |

| Legal personality | Full | Exists in both cases, both regions are subject to international law |

| Enlargement | Full | Foreseen in legal set-up and practiced in reality |

| Bodies | Medium to low | Similarity on Summit, Council and Coreper level. Difference at Secretariat capacity, Parliamentary bodies, role of the Court, Central Bank and others. |

| Voting | Very low | Consultation and consensus for ASEAN. Qualified majority voting and codecision between the Council and the European Parliament used in majority of policies. |

| Non-respect of rules | Low | In ASEAN it is a political process whilst in the EU there are infringements and law rulings |

| Budget | Low | ASEAN-9 million USD (Secretariat) and 300 million USD trust fund (2014). EU-around 1% of the GNI. |

| Harmonisation by law | None | Not used in ASEAN, key instruments in the EU |

Unlike the comparison of principles and values, the comparative picture of the institutions and working methods used by both regions is quite different. The main differences are in institutions where ASEAN is disposing of a light Secretariat only whilst The EU has a complex system of institutions. Additionally, there are other consultative and advisory bodies. The EU discards a strong administrative apparatus, enabling it to draw analyses, draft laws, monitor the implementation of laws, and take restrictive measures if necessary.

An institutional set-up provides a balance between the national interests of The EU Member States EU-wide interests.

Decision processes in both regions vary. An ASEAN Member State cannot in principle be outvoted, and, the summit can adopt an ad hoc decision. The EU Member States share sovereignty, according to policy. They cannot be outvoted in policies, while in the majority of EU policies, the Council decides by qualified majority.. Once adopted, the EU members/bodies are required to implement EU law. In cases of lowered-respect, The European Commission is required to instigate an infringement procedure, and the European Court of Justice to issue a binding ruling. In the case of ASEAN, dispute settlement mechanisms are brought into effect.

The size of the budgets between regions also differ, and which in the case of ASEAN, covers only basic secretariat functions ,while in The EU, becomes an instrument for several major policies (Regional, Agricultural, Research and Innovation, Energy, Justice and Home affairs, External ).

The comparison above demonstrates that the ASEAN way is driven more by political commitments built up and implemented through the process of national scrutiny.

On economic governance, the situation in both regions has evolved considerably, due to crises experienced in each of the regions. Economic governance involves macro-economic cooperation, financial-services regulation, budgetary surveillance, monetary cooperation, taxation, and rescue facilities. Table 3 provides an overview of the situation.

Table 3: Economic Governance in the ASEAN and the EU

| Parameter | Level of Similarity | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Marco-economic cooperation including budgetary surveillance | Low | Monitoring/recommendation only in ASEAN (AMRO). Legally binding/sanction based in The EU (TFEU, TSCG), secondary legislation (Two-pack, Six-pack). |

| Financial Services Regulation | Low to medium | Financial Service Liberalisation, Capital Account Liberalisation, Capital Market Development in ASEAN with objective of rule harmonisation and allowing ASEAN-wide banking operations. In The EU, harmonisation of rules on financial services and creation of ambitious banking union with EU-wide banking supervision and resolution. |

| Monetary cooperation | None | Non-existent in ASEAN. Shared monetary policy for Euro EU Members. |

| Taxation | None | Non-existent in ASEAN. Tax harmonisation in EU governed by unanimity voting in Council and strengthened by political commitment for Eurozone EU Members (Euro Plus Pact). |

| Rescue facilities | Medium | In ASEAN, ad hoc mechanism of CMIM. In EU, balance of payment mechanism, EFSF and ESM mechanisms based on inter-governmental set-up of Eurozone Members. |

| Variable geography | None | ASEAN implemented beyond border ASEAN+3. Certain elements of EU economic governance implemented to not all EU Members (EU 28 minus formula). |

Starting with distinct objectives and using methods which were not comparable, both regions adopted measures in a similar direction after the crisis. Both regions agreed on an “assistance-surveillance approach, meaning that they have created their own regional assistance facilities (in The EU, it was the balance of payment, EFSF, and ESM, while in ASEAN it was The CMIM) which were accompanied by stronger surveillance of the Members’ macro-economic and budgetary policies. The difference between ASEAN and EU approaches lies in the use or not of a normative instrument in economic governance.

Second parallel development represents the integration of the financial services and banking union. Here as well, the starting point has been rather different. ASEAN had originally no regulatory convergence in this sector, and was exposed to the large heterogeneity of their banks operating in both developed and developing economies of its Members. With the adoption of the Economic Blueprint, ASEAN agreed to create a single market, which included financial services and banking sectors. It used a pragmatic opt out approach for banks associated with less developed regions. A motivation of ASEAN was the creation of a more resilient financial sector, and to generate economic growth. In The EU, the internal market had been already achieved in financial services before the 2008 sovereign debt crisis in The Eurozone. The EU’s banking union project has been motivated by financial stability concerns. The Eurozone members agreed on the possibility of using the assistant facilities for troubled banks so to cut off the vicious circle between sovereign agents and banks. A precondition for this was a single supervisory mechanism and single resolution mechanism. The speedy adoption of the banking union by 2014 is seen as a qualitative step in the European integration process where a transfer of sovereignty is substantial. This development was only possible due to the existential threat to The Eurozone;, an issue for intensive political and public controversies.

The third comparison looks at the geographical scope of economic governance in both regions. ASEAN’s economic instruments have enjoyed broader support beyond ASEAN limits. ASEAN managed to engage “plus 3” countries to be part of its assistance mechanisms. The ASEAN working method of consensus and preserving national sovereignty proved its attractiveness in this respect, especially if accounting for that “plus 3” countries are economically much more relevant than ASEAN itself. The assistance architecture of ASEAN is also due to the political motivation of the Asian countries to be able to shape their own policies and to be less dependent on the global economic governance coming from IMF. On the EU side, several economic governance instruments, contrary to the ASEAN situation, have been used in a “minus formula,” that is,not binding for all EU members. The examples of such a more narrow approach include the EFSF, ESM, the Euro Plus Pact, the TSCG, and The Banking Union.

The conclusions that can be drawn from the ASEAN and EU comparison would suggest that both regions are built on a compatible set of principles and values, are using different working methods and institutions, and have converging approaches to solve their regional economic crises although using different means.

ASEAN and The EU have a long history of partnership. Despite the geographical distance between the two regions, both groupings share same values (peace, stability, and prosperity) and are based on regional integration models. Economic cooperation, especially trade, have been the core. The EU is the third most important trading partner for ASEAN, with a total trade of goods and services of 215 billion Euro in 2011. ASEAN is the fifth largest market for EU trade (EU-ASEAN, 2013). EU companies are also the biggest foreign direct investors in ASEAN countries (EU-ASEAN, 2013).

The track record of the institutional cooperation between The EU and ASEAN goes back to 1972, first at an informal level. The ASEAN Ministerial Meeting of Foreign Ministers arrived at an agreement in 1977 with a formal cooperation with The EU. The first ASEAN Ministerial Meeting took place in Brussels in 1978. This was followed two years later by The European Community - ASEAN Cooperation Agreement, which created the joint Cooperation Committee. In the 90’s, a strategic reflection occurred between the two blocks, on how to best cooperate in the post-Cold War situation. The Eminent Persons Group created in 1994 was the forum for this reflection.

As the ASEAN model spread to South East Asia beyond the ASEAN border, the first EU and ASEAN+3 Summit took place in 1996 in Bangkok, and gave birth to the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM).

On the EU side, the strategic character of the link between the two regions was captured in a European Commission document, “A New Partnership with South East Asia”. It was followed by the Nuremberg Declaration on an Enhanced EU-ASEAN Partnership in 2007, accompanied by a Plan of Action for its implementation. Five years later, the Bandar Seri Begawan Plan of Action to Strengthen the ASEAN-EU Enhanced Partnership (2013-2017) was signed (ASEAN-EU, 2012 - EU-ASEAN, 2012 - ASEAN-EU, 2012 - ASEAN-EU, 2012): Table 4 provides an overview of its structure and focus. On the diplomatic side, The EU and its Member states sent their ambassadors to ASEAN. On February 27, 2014, the first meeting of The ASEAN Committee of Permanent Representatives met with their EU counterparts, COREPER (Committee of the Permanent Representatives).

Table 4: Overview of the ASEAN-EU Enhanced Partnership (2013-17)

| Policy Type | Number of measures |

|---|---|

| Enhancing political dialogue | 1 |

| Promoting regional cooperation for peace, security, and stability | 19 |

| Cooperation on human rights | 1 |

| Cooperation in Regional and International Fora | 1 |

| General Economic Cooperation | 14 |

| Trade and Investment | 8 |

| Small and Medium Enterprises | 1 |

| Transport | 2 |

| Food, agriculture and forestry | 1 |

| Energy security | 5 |

| Tourism | 1 |

| Enhancing cooperation in education, health, & promoting people-to-people contacts | 10 |

| Promoting gender equality, well-being of women, children, the elderly and persons with disabilities & migrant workers | 2 |

| Building together disaster-resilient communities | 6 |

| Promoting cooperation in Science and Technology | 4 |

| Enhancing food security and safety | 1 |

| Working together to face regional and global environmental challenges | 6 |

| Institutional support to ASEAN | 3 |

| Follow-up Mechanism | 3 |

The rich history of the EU-ASEAN cooperation mirrors the fact that, broadly speaking, both groupings were successful in their missions. There was no military conflict in either of the regions, and economic prosperity was apparent. The individual success of both integrations and their mutual contacts have inspired other regions around the globe to follow similar paths, such as the African Union, Mercosur and the Commonwealth of Independent States/Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU).

Looking forward, EU and ASEAN relations will probably have two types of issues on their agenda (EU-ASEAN, 2013 - Le Luong Minh, 2013). The first would be their mutual interest to block relations, and the second would be their joint efforts in shaping a multilateral agenda globally.

Firstly, with reference to block to block relations, the medium-term plan has been established in the Bandar Seri Begawan Plan of Action to Strengthen the ASEAN-EU Enhanced Partnership (2013-2017). This includes cooperation on maintaining peace, security, and stability. Both The EU and ASEAN are soft powers who employ the method of preventative diplomacy rule of law, institutional cooperation, and attractiveness of their models as an instrument to deliver their objectives. The EU has envisaged its current financial perspective (2014-20) for the ASEAN integration and ASEAN Secretariat as 170 million Euro. This is more than double of an effort under the previous Development Cooperation Instrument which benchmarked 70 million Euro for the period 2007-2013. The new support will focus on strengthening connectivity, building disaster management measures, climate change programs, and facilitating cross-border dialogue.

To deliver on these objectives, The ASEAN Regional Forum would be key. The Preventive Diplomacy Work Plan is an instrument with which to deliver concrete activities and actions. ASEAN has a potential to be promoter of conflict prevention, reconciliation, and peace building, and The EU will support this. Similarly, the EU will join ASEAN efforts in combatting sea piracy and promoting maritime safety. Institutional cooperation between The EU and ASEAN will continue to combat trans-national crime. ASEAN and The EU will jointly fight against terrorism (ASEAN-EU Joint Declaration on Cooperation to Combat Terrorism) and to enforce international goals. Border management, anti-corruption fighting and disarmament, and non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, will also be high on the joint agenda.

On the economic side, each block is now institutionally much more deeply integrated. This integration path followed the recent crisis in each of the regions. As a result, the long-term cooperation could be based on more stable foundations. The European financial sector should be more resilient to future crises via the implementation of the Banking Union. The growth oriented agenda of Europe 2020 on the EU side creates more opportunities for ASEAN partners. The Euro zone can be seen as more stable due to the stronger rules and controls over the public budgets of its members, and due to the creation of various new safeguard mechanisms. Similarly, on the ASEAN side, the creation of the single market, presents an opportunity for European business. Involvement of the ASEAN economic governance in the ASEAN+3 region represents yet another opportunity for European companies.

Trade will remain a priority on the agenda between the two regions. The recent Free Trade Agreement between The EU and Singapore and ongoing negotiations with Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam can be seen as first steps towards trade liberalisation. From a more strategic perspective, and considering the integration dynamics within ASEAN, a natural development should lead both regions towards concluding a block-to-block free trade agreement in the future.

Economic and territorial cohesion is another joint issue, the creation of the internal market in The EU has been followed by a massive effort to create physical infrastructure for connectivity, especially in the cross-border territories. The European Development and Investments Funds serves as an instrument. Here, the EU can assist ASEAN to achieve its Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity adopted at the ASEAN Summit in 2010.

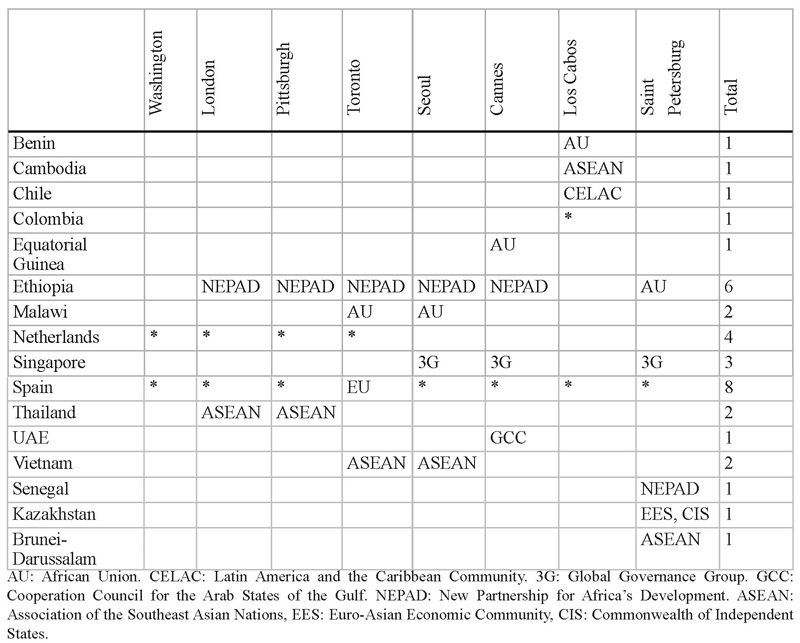

Secondly, with reference to multilateral relations globally, The EU and ASEAN are synergy partners, such as in that both regions are promoters of a multilateral approach in international relations. In the recent past, , both regions have had a place at the G20 table. In the period 2008-2013, ASEAN was invited as an observer six times (see Table 5) while The EU was present at each summit. The fact that the regional groupings are represented at the G20 format, makes regional integration more attractive and relevant globally.

Table 5: Stakeholders of the G20 summits

ASEAN and The EU therefore have interest to coordinate mutually in the areas which are dealt with at The G20. This covers growth related policy coordination, creating a sound framework for the financial sector, and trade liberalisation. In addition to these core issues, ASEAN and The EU can mutually support themselves in development efforts, food security, employment, energy, combatting tax evasion, and anti-corruption. In all these areas, the ultimate goals of both regions are mutually compatible. Similarly, The EU and ASEAN can join their efforts in other international for a, such as the United Nations, global climate dialogue, The World Trade Organisation, and others, so to tackle jointly the issues of sustainability, prosperity, and peace. The upcoming ASEM Summit in October 2014 in Milan with 51 partners would present an opportunity in this sense.

The article looked at the recent developments in The European Union, and in ASEAN, as well as at the cooperation between two regions.

The paper argued that both regions share values and use similar methods so to achieve these methods within their respective territories. Both regions have also recently been suffering from financial and economic crises. Eventually, both regions have taken lessons from the crises, resulting inmuch deeper internal cooperation and strengthening integration efforts.

ASEAN reacted to its financial crisis mainly by strengthening its economic governance. It created mechanisms of financial stability and solidarity, accompanied by closer surveillance of macro-economic policies, even though the economic governance in ASEAN remains light, the trend towards more coordination is visible. ASEAN also decided to create a three pillar community’s architecture covering political, economical and social cultural policies. It decided to create a single market by 2015, based on the legally binding commitment of the ASEAN Charter. ASEAN also achieved certain “ASEAN centricity” in South East Asian regions by creating an ASEAN+3 format for political dialogue and economic governance.

The EU suffered from a sovereign debt crisis which tested the viability of its single currency. The EU decided to strengthen the internal mechanisms and to move towards a genuine economic and monetary union. It has strengthened the collective control mechanism over its members in terms of supervising their fiscal policy and growth related reforms. This tougher coordination was complemented with the mechanism of solidarity, so to mutually assist the stressed members of the Euro zone. Additionally, the European Union agreed on a Banking Union. This is a major development, comparable with the creation of the Internal Market. The European Union has recently became more integrated than before the crisis. This, combined with a forced entry into the Lisbon Treaty, which strengthens the external dimension and representation of the European Union, creates new momentum for The EU to enter into relations with ASEAN.

EU/ASEAN relations, which have had a history of more than 40 years, became formalised through institutional contacts and enhanced partnership. The current Bandar Seri Begawani Plan for 2013-17 draws a concrete list of cooperation in political, economic, and socio-cultural areas.

Looking at the future, the paper concluded that EU/ASEAN relations may have two dimensions; The first one being in block-to-block cooperation. This will cover trade, security, non-traditional security, human rights, and physical connectivity. The second type of coordination may lead to joint efforts through a multilateral framework. Both regions can jointly cooperate at the international for a, such as at G20, The WTO, ASEM, or climate oriented fora. In doing so, they can achieve two results: progress in the policy area concerned and regional cooperation, presenting an attractive model for other global regions.

Acharya, A. 2009. Whose ideas matter? Agency and power in Asian regionalism, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Alcidi, C. and Gross, D. (2014): Implications of EU governance reforms: rationale and practical application. Think Tank Review (TTR) 14/2014

ASEAN-EU (2012): Co-Chairs’ Statement of the 19th ASEAN-EU Ministerial Meeting 26-27 April 2012 in Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei Darussalam

ASEAN-EU (2012): Joint Press Release 19th ASEAN-EU Ministerial Meeting 26 -27 April 2012 in Bandar Seri Begawan - 35 years of Friendship and Cooperation

ASEAN-EU (2012): Bandar Seri Begawan Plan of Action to Strengthen the ASEAN-EU Enhanced Partnership (2013-2017).

ASEM (2013): 11th ASEM Foreign Ministers’ Meeting (ASEM FMM11) Delhi-NCR, India, November 11-12, 2013 - ASEM: Bridge to Partnership for Growth and Development

Ayson, R. and Taylor, B. 2009. “Architectural alternatives or alternatives to architecture?”. In Rising China: Power and Reassurance, Edited by: Huisken, R. 185–99. Canberra: ANU E Press

Bilbao-Ubillos, J. (2014): The economic crisis and governance in the European Union: a critical assessment. Routledge, 2014 -- XIV, 201 p. Routledge Studies in the Economic Economy 28

Börzel, T. and Risse, T. (2009): The Transformative Power of Europe. The European Union and the Diffusion of Ideas. Kolleg-Forschergruppe The Transformative Power of Europe, Working Paper 1

Caballero-Anthony, M. (2008): The ASEAN charter: an opportunity missed or one that cannot be missed?. Southeast Asian Affairs, : 71–85

Capannelli, G. (2009): Asian regionalism: how does it compare to Europe’s?. East Asian Forum

Capellini, G. and Filippini, C. (2009): “East Asian and European Economic Integration: A Comparative Analysis”. Working Paper Series on Regional Economic Integration No. 29 21Asian Development Bank. May

Clerc, O. and Grard, L. (2012): La gouvernance économique de l’Union Européenne, Bruylant.

Craig, P. (2012): The Stability, Coordination and Governance Treaty: principle, politics and pragmatism, European Law Review, 37.

de Gregorio Merino, A. (2012): Legal developments in the Economic and Monetary Union during the debt crisis: the mechanisms of financial assistance” , Common Market Law Review, n. 10, 2012, pages 101-108.

Dent, C.M. (2008): East Asian regionalism, London: Routledge

Desker, B. (2008): New security dimensions in the Asia-Pacific. Asia-Pacific Review, 15(1): 56–75

EU-ASEAN (2012): Joint Declaration on EU-ASEAN Aviation Cooperation - Adopted at the first EU-ASEAN Aviation Summit in Singapore, 11-12 February 2014

EU-ASEAN (2013): EU-ASEAN Conference Stresses the Need to Move Ties to a Higher Level

EU-ASEAN (2013): EU-ASEAN: Natural Partners. June 2013 (7th edition), EU Delegation, Jakarta

Fabrinni, S. (2013): Intergovernmentalism and its limits: assessing the European Union’s answer to the euro crisis. Comparative political studies 2013, June

Gabor, D. (2014): Banking Union: a response to Europe’s fragile financial integration dreams? Think Tank Review (TTR) 14/2014

Giessmann, H. (2007): Regionalism and crisis prevention in (Western) Europe and (Eastern) Asia: a systematic comparison. Asia-Pacific Review, 14(2): 62–81

Hammilton-Hart, N. (2011): Regional Governance: East Asia after the Global Financial Crisis. Workshop on Leadership, Decision-making and Governance in the EU and East Asia: Crisis and Post-crisis. EU Centre in Singapore, 21-22 November 2011. Singapore

Hout, W. (2012): EU strategies on governance reform: between development an state-building. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012. Third World Quarterly, vol. 31 , issue 1

Islam, S. (2010): “Europe and Asia as global security actors”. 15–18. Brussels ASEM 8 visibility support in view of the ASEM 8 summit Brussels, July 2010

Jetschke, A. 2009. Institutionalizing ASEAN: celebrating Europe through network governance. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 22(3): 407–26

Katsumata, H. (2006): Establishment of the ASEAN Regional Forum, constructing talking shop or a ‘norm brewery’. The Pacific Review, 19(2): 181–98

Kawai, M. (2007): “Evolving regional financial architecture in East Asia”. In Regional Outlook Southeast Asia 2007–2008, Vol. 77'83, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies

Le Luong Minh (2013): Keynote Address EU-ASEAN Economic & Policy Forum by H.E. Le Luong Minh Secretary-General of ASEAN

Levine, S. (2007): Asian values and the Asia Pacific community: shared interests and common concerns. Politics and Policy, 35(1): 102–35

Mahbubani, K. (2008): The new Asian hemisphere. The irresistible shift of global power to the East, New York: Public Affairs

Morada, N. 2008. ASEAN at 40: prospects for community building in Southeast Asia. Asia-Pacific Review, 15(1): 36–55

Murray, P. (2005): “Should Asia emulate Europe?”. In Regional integration — Europe and Asia compared, Edited by: Moon, W. and Andreosso-O’Callaghan, B. 197–215. Ashgate: Aldershot. 2005

Murray, P. 2010. Comparative regional integration in the EU and East Asia: moving beyond integration snobbery. International Politics, 47(3–4, May–July): 308–29

Narine, S. (2009): ASEAN and regional governance after the Cold War: from regional order to regional community?. The Pacific Review, 22(1): 91–118

Piris, J.C. (2011): The future of Europe: Towards a two speed EU?, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 97-811-076-62-568

Ravenhill, J. (2007): In search of an East Asian region: beyond network power, roundtable: Peter J. Katzenstein’s contributions to the study of East Asian regionalism. Journal of East Asian Studies, 3: 387–94

Schimmelfennig, F. (2009): Europeanization beyond Europe. Living Reviews in European Governance, 4(3) http://www.livingreviews.org/lreg-2009-3

Soesastro, H. and Drysdale, P. (2009): Thinking about the Asia Pacific Community. East Asian Forum

Tay, S. 2009. ASEAN remains important. Global Citizens, http://globalcitizens.siiaonline.org/?q=blog/asean-a-re-think-needed (accessed 3 November 2009)

Tow, W. Tangled webs. Security architectures in Asia, Strategy Paper, Australian Strategic Policy Institute. July, Canberra

Tow, W. and Taylor, B. 2010. What is Asian security architecture?. Review of International Studies, 36: 95–116

Woolcott, R. (2009): An Asia Pacific community: an idea whose time is coming. East Asian Forum, 18 October

Yeo, L.H. (2009): The Everlasting Love for Comparison: Reflections on the EU’s and ASEEAN’s Integration. In: Kanet, R., E., ed.: The United States of Europe in a Changing World. Dodrecht Republic of Letters Publishing, pp. 185-205

Yeo, L.H. (2011): Where is ASEAN Heading - Towards a Network Approach to Global Governance? In: Panorama: Insights into Asian and European Affairs. Asia and Europe moving towards a common agenda. Konrad Adenaurer Stiftung, Singapore, p. 19-26

Yeo, L.H. (2013): How should ASEAN engage the EU? - reflections on ASEAN’s external relations. Working paper no. 13, April 2013

The ASEAN Charter (2008): Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, January 2008. ISBN 978-979-3496-62-7

Treaty on European Union (2010): Consolidated Treaties - Charter of Fundamental Rights March 2010. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. ISBN 978-92-824-2577-0

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (2010): Consolidated Treaties - Charter of Fundamental Rights March 2010. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. ISBN 978-92-824-2577-0

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union: Economic and Monetary Union - Legal and Political texts (2014) - Title VIII - Economic and Monetary Policy p.13-21. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. ISBN 978-92-824-4208-1

Last Update: 24/12/2021