AEI-Insights: An International Journal of Asia-Europe Relations

ISSN: 2289-800X, Vol. 9, Issue 1, July 2023

DOI: https://doi.org/10.37353/aei-insights.vol9.issue1.4

Fumitaka Furuoka

Asia-Europe Institute, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

fumitaka@um.edu.my

Abstract

This paper examines the impact of financial development on economic growth in Asia. In other words, the objective of current paper is to examine the relationship between economic growth and financial development in 10 countries in Asia. It employs systematic time-series econometric methods, namely, the unit root test, the cointegration test, the cointegrating regression analysis, the vector error correction analysis and the Granger causality analysis. The source of data was the “World Development Indicators”. The empirical findings indicated some interesting characteristics in the finance–development nexus in Asia. Interesting findings that financial development could contribute financial development in Singapore only. By contrast, economic growth may induce financial development in China and Pakistan. These findings have some notable policy implications. Singaporean government may need to understand the importance of financial sector in its economy.

Keywords: Financial development, economic growth, Asia

Introduction

There is little doubt that the financial sector would play a vital role in the process of economic growth. Without a financial sector, poor people may need to borrow money from family, friends or the money lenders with very high interest rates. World literature often describes evil characters of money lenders, such as Mr Ebenezer Scrooge in Charles Dickens’s novel “A Christmas Carol”. Ebenezer Scrooge is an old and stingy money lender in London who refused to celebrate the Christmas in order to save his money (Dickens, 2006). Today, there are also various stories of personal bankruptcies in which poor people needed to take loans with high interest rates and could not pay back their debts in the end.

In a broader economic growth perspective, the financial sector would play an important role to connect the “savings” and the “investments”. The modern growth economic theory stipulates that the investment would be a driving force to stimulate economic growth. Thus, there are numerous research to explain the beneficial relationship between financial development and economic growth. Among others, the pioneer research on this topic is conducted by Patrick (1966). He claimed that there are three ways for financial sector to influence the economic growth. Firstly, the financial sector could contribute to create more efficient allocation of capital. Secondly, the financial sector could play a mediation role between savers and firms. Thirdly, the financial sector could encourage savers to save more money by providing better incentive. In this study, financial development could be defined as the credit to private sector as the percentage of GDP is used as a proxy to measure the financial development (King and Levine, 1992; Agbetsiafa, 2004; Appiah‐Otoo and Song, 2022).

Furthermore, Mathieson (1980) claims that many developing countries suffers from various kinds of financial distortion, such as the “interest ceiling” policies, which hampers economic growth because these distortions of financial sector may generate a lower “saving-investment” ratio. These countries may stimulate economic growth by rectifying this financial market distortion and eliminating these “interest ceiling” policies. Similarly, Pagano (1993) claimed that there are two main aspects for financial sector’s contribution to economic growth. Firstly, the financial sector would channel savings to firms as a source of investment. In other words, without appropriate financial development, there would be a lower saving-investment ratio. Secondly, the financial sector would allocate efficiently existing financial assets to firms. Without appropriate financial development, there would be inefficiency in the financial allocation. The main issue in the financial development in Asia is that policymakers are not keen to open their financial markets. From a theoretical perspective, development of financial markets would have positive impact on economic growth in Asia. However, there are some disagreements among researchers and practitioners whether financial sector would really have beneficial impact on Asian economic growth (Fry, 1995).

There is numerous existing research on this topic (Jung, 1986; Agbetsiafa, 2004; Chang and Huang, 2010; Furuoka, 2017). Despite this importance, there is no consensus whether the financial sector would have impact on economic growth (Furuoka, 2015, Ismihan et al. 2016; Furuoka, 2016). Thus, this research will examine the relationship between financial development and economic growth in ten Asian countries It employs systematic time-series econometric methods, such as the unit root test, the cointegration test, the cointegrating regression analysis, the vector error correction analysis and the Granger causality analysis. Despite its importance, the finance-growth nexus is empirically examined mainly in the context of America or Europe. In other words, there is lack of systematic empirical research to examine the relationship between financial development and economic growth in Asia. For a historical perspective, some Asian countries, such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and South Korea, suffered from the Asian economic crisis in the end of the 1990s. As a result, the policymakers in Asian countries may become more cautious about an excessive liberalization of financial sectors and this reluctancy of financial policymakers would negatively affect the finance-growth nexus in the region. However, there is no empirical proof for this interesting topic due to lack of systematic research. The main contribution of current study is to fill this research gap and to analyse this topic in the context of Asia.

This paper consists of five parts. Following this introductory section, the second section offer a theoretical foundation to link financial development with economic growth. The third section is the literature review on the previous analysis of the finance-growth nexus. The fourth section discusses about data and methods to examine the relationship between financial development and economic growth. The fifth section reports the empirical findings. The sixth section is conclusion.

Theoretical perspective

The neoclassical economic theory provides a useful theoretical framework to understand the important role of the financial sector in the economic growth process (Harrod, 1939, Domar, 1946; Solow, 1956). Firstly, the growth theory clearly show that the investment is the main ingredient for economic growth. According to the theory, economic growth rate could be equal to the growth rate of capital. This equality of income growth and capital growth could be considered as the first fundamental assumption in the growth theory. Secondly, the growth theory assumes that change in capital is equal to amount of new investment minus amount of capital depreciation. In this context, investment rate could be equal to the saving rate. The equality of investment and saving could be considered as the second fundamental assumption in the growth economics.

By combing these two assumptions, the rate of economic growth is equal to the saving rate time average product of capital minus capital depreciation rate. The question is: how does the financial sector contribute to economic growth? The simple answer is that the financial sector would play a role to ensure the equality of saving and investment in the second assumption. In other words, it is not an automatic process that the saving would be transformed into the investment. Without the financial sector, savings would be smoothly and efficiently brought to the hands of the investor.

Important role of financial sector could be highlighted by interactions between the “borrowing” and “lending” through financial sector. This interaction could be expressed as two different transactions, namely the “borrowing” process and the “lending” process. In the first financial transaction, the financial sector would “borrow” the money from savers by selling them financial goods. The savers are those who save the balance between income and expenditure. In this transaction, the saving (S) would be transformed into the financial good (F), such as stock, bond, deposit or insurance policies or so on. In the second financial transaction, the financial sector would “lend” the money to the entrepreneurs by giving them loans. The entrepreneurs are those who make investments on productive resources. In this “borrowing” transaction, money obtained from the financial good (F) would be transformed into investment (I).

In a nutshell, the financial sectors would play two important roles in the “metamorphosis” of the saving into the investments. Firstly, the financial sector may contribute to increase and encourage the savings by offering attractive financial goods. If there are no sound financial sectors, the countries may suffer from the low saving rate. Secondly, the financial sector may contribute to better allocation of financial resource by providing more money to better entrepreneurs. If there are no sound financial sectors, the countries may suffer from misallocation of limited financial resources.

Literature review of empirical studies

There are numerous empirical studies that have examined the relationship between financial development and economic growth. This important topic in financial economics is known as the finance-growth nexus. There are several researchers who have conducted empirical analyses on this topic since the 1980s. For example, Jung (1986) employed the Granger causality test to examine the causal relationship between financial development and economic growth in 51 countries for the period of the 1951-1981. Out of these 56 countries, there is causality from financial development to economic growth in 34 countries. Jung concluded that financial development does contribute economic growth in these countries. King and Levine (1992) used the correlation analysis to examine the relationship between ratio of domestic credit in private sector to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 119 countries for the period of 1960-1989. They claimed that there is a significant correlational relationship between financial sector and economic growth in these countries. Wang (1999) used Seemingly Unrelated Regression Equation (SURE) method to examine the relationship between financial development and economic growth in Taiwan for the period of 1961-1985. The researcher concluded that financial development would have a positive impact on economic growth in Taiwan.

There is an increase in the number of empirical analyses on the finance-growth nexus since the beginning of the 2000s. For example, Agbetsiafa (2004) also used the Granger causality test to examine the finance-growth nexus in eight Sub-Saharan countries in Africa for the period of 1963-2001. Out of eight countries, the causality from financial development to economic growth in only two countries. Valverde and Fernández (2004) used the panel Granger causality test to examine the financial development and economic growth in 17 regions in Spain for the period of 1993-1999. They claim that financial development would not cause economic growth in Spain. Instead, they asserted that there is a reversal causality from economic growth to financial development in country. Hahn (2005) employed the panel regression method to examine the relationship between financial development and economic growth in 21 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries for the period of 1971-1998. The researcher claimed that there is statistically significant positive relationship between financial development and economic growth. In other words, he concluded that financial deepening would stimulate economic growth in these OECD countries. In the case of Turkey, Ozturk (2008) used the vector autoregression (VAR) method to examine the relationship between financial development and economic growth in Turkey for the period of 1975-2005. He pointed that the Granger causality test failed to reject the null hypothesis of no causality from financial development to economic growth. However, the Granger causality could reject to null hypothesis of reverse causality. In line with findings from Valverde and Fernández (2004), Ozturk detected the unidirectional causality from economic growth to financial development.

In the 2010s, the finance-growth nexus is still popular topic. There are several researchers used some advanced economic methods, such as structural break regression analysis, generalized impulse response analysis and panel threshold regression, to examine the topic. For example, Chang and Huang (2010) used the structural break regression method to examine the relationship between financial development and economic growth in Japan for the period of 1981-2008. They claimed that the regression analysis indicated a significant relationship between financial development and economic growth in Japan. However, the structural break regression method indicated that finance-growth relationship is only statistically significant for the period of 1981-1995. After that period, there is no significant relationship between financial development and economic growth in Japan. Dal Colle (2011) also used the vector autoregression (VAR) method to examine the relationship between financial development and economic growth in 12 developing countries for the period of 1961-2007. The researcher claimed that there is unidirectional causality from financial development to economic growth only one country, Colombia. By contrast, there is unidirectional causality from economic growth to financial development in two countries, namely China and Ghana. Dal Colle claimed that there is no empirical evidence to support that the causality from the finance to economic growth. Ismihan et al. (2016) employed the generalized impulse response (GIR) analysis to examine the relationship between financial development and economic growth in Turkey for the period of 1980-2010. They claimed that the GIR method detect the significant impact of financial development on economic growth. At same time, the economic growth also would have impact on the financial development. They concluded that there is bidirectional causality between financial development and economic growth. Slesman et al. (2019) used the panel threshold regression to examine the finance-growth nexus in 77 developing countries for the period of 1976-2010. They pointed out that there is no significant finance-growth relationship in the countries with poor political institution. By contrast, there is a significant relationship between financial development and economic growth in countries with good political institution.

More recently, Haini (2021) examine the relationship between financial development and economic growth in 51 developing countries for the period of 1996-2017. The researcher used the fixed effect model and random effect model and concluded that financial development would have positive impact on economic growth in these developing countries. Iwasaki (2022) used the meta-analysis method to examine to the finance-growth nexus in the Latin America and Caribbean countries. The researcher asserted that financial development would have beneficial impact on the economic growth in the region. The researcher also claimed that the policy to liberalise the final market would bring positive impact on economic growth in the Latin America and Caribbean countries. Furthermore, Appiah‐Otoo and Song (2022) used time-series methods, such as the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) method and the fully modified OLS (FMOLS) method, to examine the relationship between financial development and economic growth in Ghana. They concluded that financial development may not have beneficial effect on economic growth in the countries.

In short, the literature review of empirical analysis on the relationship between financial development and economic growth revealed that researchers would have consensus whether the financial development would have beneficial effect on economic growth. In other words, empirical analysis of this topic produced mixed results (See Table 1). To fill this empirical gap in the existing literature, current study examine the relationship between financial development and economic growth in Asian countries.

| Authors (Year) | Countries | Data | Methods | Measurement for financial development | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jung (1986) | 56 countries | Time-series data (1951-1981) | Granger causality test | Ratio of M2 to GDP | Significant causal relationship |

| King and Levine (1992) | 119 countries | Cross-sectional data (1960-1989) | Correlation analysis | Ratio of domestic credit in private sector to GDP | Significant correlational relationship |

| Wang (1999) | Taiwan | Time-series data (1961-1985) | Seemingly unrelated regression equation (SURE) | Ratio of liquid liabilities to GDP | Significant relationship |

| Agbetsiafa (2004) | 8 Sub-Saharan countries | Time-series data (1963-2001) | Granger causality test | Ratio of private credit to GDP | No significant causal relationship |

| Valverde and Fernández (2004) | Spanish region | Panel data (1993-1999) | Panel granger causality test | Outstanding values of loans | No significant causal relationship |

| Hahn (2005) | 21 OECD countries | Panel data (1971-1998) | Panel regression | Ratio of private credit to GDP | Significant relationship |

| Ozturk (2008) | Turkey | Time-series data (1975-2005) | Vector Autoregression (VAR) | Ratio of private credit to GDP | No significant causal relationship |

| Chang and Huang (2010) | Japan | Time-series data (1981-2008) | Structural break regression | Ratio of monetary claim to GDP | Significant relationship |

| Dal Colle (2011) | 12 developing countries | Time-series data (1961-2007) | Vector Autoregression (VAR) | Ratio of private credit to GDP | No significant causal relationship |

| Ismihan et al. (2016) | Turkey | Time-series data (1980-2010) | generalized impulse response analysis | Ratio of private credit to GDP | Significant causal relationship |

| Slesman et al. (2019) | 77 developing countries | Panel data (1976-101998) | Panel threshold regression | Ratio of private credit to GDP | Significant relationship |

Data and methods

This study employs systematic econometric methods to examine the relationship between financial development and economic growth in Asia for the period of 1977-2020. The main source of data is the World Development Indicators (World Bank, 2023). It contains time-series data on macroeconomic variable from 1997 to 2020. Thus, current study examines the finance-growth nexus in Asia for that period only. The number of observations is 44. Due to lack of sufficient and reliable date, this study chooses the following ten Asian countries for the empirical analysis, namely Bangladesh, China, India, Japan, Korea, Myanmar, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippines and Singapore. This study examine these Asian countries because there is empirical research on the relationship between financial development and economic growth in Asia.

The real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is used as a proxy to measure the economic growth. Based on the existing literature (King and Levine, 1992; Agbetsiafa, 2004; Appiah‐Otoo and Song, 2022), the domestic credit to private sector as the percentage of GDP is used as a proxy to measure the financial development. The source of data is the World Development Indicators. More detailed description date is reported in Table 2. Previous empirical research indicated that there would be significant positive relationship between financial development and economic growth in these Asian countries.

| Variables | Data source | Name of database | Data codes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic growth (GDP) | Gross Domestic Product (Constant, 2015, US$) | World Bank | World Development Indicators | NY.GDP.MKTP.KD |

| Financial Development (FID) | Domestic credit to private sector as percentage of GDP | World Bank | World Development Indicators | FS.AST.PRVT.GD.ZS |

There are five stages in the empirical analysis, namely unit root test, cointegration test, cointegrating regression analysis, vector error correction analysis and causality analysis. The first analysis and second analyses are used as pre-test for further analysis. The third method could be used to examine whether financial sector would have positive impact on economic growth. The fourth analysis is used to examine a short-run and run-run relationship between financial development and economic growth. The final analysis is used to examine the causal relationship in the finance-growth nexus.

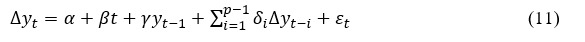

In the first stage of empirical analysis, the unit root test is used to examine the unit root process of time-series on financial development and economic development. If the time-series follows the unit root process, the lagged value of the time-series would not have a predictive power over the level values of the time-series data. For the purpose of unit root analysis, this study uses the augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test. The ADF is based on the following equation (Dickey and Fuller, 1979):

where y is the variable of interest, α is constant, t is trend, ε is error term, β, γ and δ are slope parameters. If the ADF statistics is less than critical values, null hypothesis of unit root is rejected. It would mean that the time-series could be considered as stationary process.

In the second stage of empirical analysis, the unit root test is used to examine the cointegrating relationship between two time-series data. As mentioned in the unit root test, time-series data could be considered as unit root process which would move randomly. However, if two time-series data are cointegrated, there would be a long-run relationship between them. For the purpose of cointegration analysis, this paper uses the Engle-Granger (EG) test. The EG test is based on the residuals which is obtained from the following static regression (Engle and Granger, 1987):

where y is the dependent variable and x is independent variable. The ADF test could be used to examine whether there is cointegrating relationship between dependent variable and independent variable.

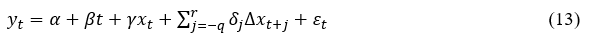

In the third stage of empirical analysis, the cointegrating regression analysis to examine the cointegration coefficient between two time-series data. The static ordinary least squares (SOLS) is not efficient method to estimate the coefficient parameter for the relationship between dependent variable and independent variable. Instead, this paper used the dynamic ordinary least squares (DOLS) to estimate the coefficient parameter for these time-series. The DOLS is based on the following equation (Stock and Watson, 1993):

where r is number of leads and q is number of lags, y is dependent variable and x is independent variable. In the DOLS analysis, estimation equation would incorporate the leads and lags of the differenced independent variable so that the error term is not independent to the independent variable.

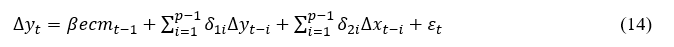

In the fourth stage of empirical analysis, the vector error correction (VEC) analysis to examine the long-run relationship between two time-series data. The coefficient parameter for the error correction term (ECT) could be used to examine the long-run relationship between dependent variable and independent variable. The coefficient parameter for lagged values of first-difference variable could be used to examine the short-run relationship between them. The VEC analysis is based on the following equation (Sims, 1980):

where ecm is error correction term, y is dependent variable and x is independent variable. The significant error correction terms would indicate that there is a long run relationship between independent and dependent variable while the significant differenced variables would indicate that there is a short run relationship.

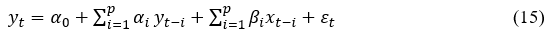

In the fifth stage of empirical analysis, the Granger causality analysis to examine causal relationship between two time-series data. If a lagged value of independent variable has a significant predicative power over dependent variable, the independent variable is considered to cause the dependent variable. The Granger causality test is based on the following equation (Granger, 1969):

The Granger test is based on the joint hypothesis: β1=β2=⋯=βi=0. If the F-test rejected the joint hypothesis, independent variable would “Granger” cause dependent variable.

Empirical findings

Table 3 reports the empirical findings from the ADF test on economic growth (GDP). As the findings in the table indicated, the ADF test failed to reject the null hypothesis of unit root with constant at the level of GDP for all ten countries, except for India and Japan. Similarly, the ADF test failed to reject the null hypothesis of unit root with constant and trend at the level of GDP for all ten countries, except for India and Korea. It means that time-series on economic growth in Asian countries are not stationary at the level. On the other hand, the ADF test could reject the null hypothesis of unit root with constant at the first-difference of GDP for Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan and Singapore. Similarly, the ADF test could reject the null hypothesis of unit root with constant and trend at the first-difference of GDP for Japan, Korea, Malaysia, and Singapore. It also means that time-series on economic growth in Asian countries could be considered as a stationary process at the first-difference.

| Level | First difference | |||

| Country | Constant | Constant and Trend | Constant | Constant and Trend |

| Bangladesh | 4.764 | 3.353 | -0.240 | -2.403 |

| China | -2.240 | -2.491 | -1.628 | -1.655 |

| India | -3.080** | -3.805** | -2.098 | -1.148 |

| Japan | -2.873* | -0.751 | -2.759* | -3.891** |

| Korea | 1.434 | -3.531** | -3.940*** | -4.348*** |

| Myanmar | 2.345 | 0.790 | -0.781 | -2.538 |

| Malaysia | 1.340 | -1.718 | -3.048** | -3.639** |

| Pakistan | 0.295 | -2.275 | -2.896* | -2.963 |

| Philippines | -0.220 | -1.763 | -2.333 | -2.458 |

| Singapore | 0.614 | -1.997 | -3.243** | -3.464* |

Note: * indicates significant at the 1 percent level, ** indicates significant at the 5 percent level, *** indicates significant at the 10 percent level, the critical values of ADF test (with constant only) for 1 percent level, 5 percent level, and 10 percent level are -3.5, -2.9 and -2.6 respectively and the critical values of ADF test (with constant and trend) for 1 percent level, 5 percent level, and 10 percent level are -4.1, -3.5 and -3.1 respectively.

Table 4 reports the empirical findings from the ADF test on financial development (FID). As the findings in the table indicated, the ADF test failed to reject the null hypothesis of unit root with constant at the level of FID for all ten countries. Similarly, the ADF test also failed to reject the null hypothesis of unit root with constant and trend at the level of FIN for all these ten countries. It means that time-series on financial development in Asian countries are not stationary at the level. On the other hand, the ADF test could reject the null hypothesis of unit root with constant at the first-difference of FID for all ten Asian countries, except India. Similarly, the ADF test could reject the null hypothesis of unit root with constant and trend at the first-difference of FID for these nine countries. It also means that financial development growth in Asian countries could be considered as a stationary process at the first-difference.

| Level | First difference | |||

| Country | Constant | Constant and Trend | Constant | Constant and Trend |

| Bangladesh | -1.025 | -1.486 | -4.501*** | -4.527*** |

| China | 0.609 | -2.026 | -5.157*** | -5.272*** |

| India | 0.273 | -1.405 | -2.418 | -2.497 |

| Japan | -1.938 | -1.916 | -3.243** | -3.149* |

| Korea | 0.178 | -2.146 | -3.966*** | -4.035** |

| Myanmar | -0.347 | -1.453 | -3.928*** | -4.178*** |

| Malaysia | -2.163 | -2.169 | -4.502*** | -4.585*** |

| Pakistan | -1.164 | -2.535 | -3.937*** | -3.943** |

| Philippines | -1.173 | -2.276 | -3.304** | -3.427* |

| Singapore | -1.106 | -2.442 | -4.064*** | -3.981** |

Note: * indicates significant at the 1 percent level, ** indicates significant at the 5 percent level, *** indicates significant at the 10 percent level, the critical values of ADF test (with constant only) for 1 percent level, 5 percent level, and 10 percent level are -3.5, -2.9 and -2.6 respectively and the critical values of ADF test (with constant and trend) for 1 percent level, 5 percent level, and 10 percent level are -4.1, -3.5 and -3.1 respectively.

Despite some minor discrepancies in the empirical findings, the ADF test indicated the unit root test could reject the null hypothesis of unit root at the first-difference in the over-majority of countries in Asia. In other words, that time-series data on economic growth and financial development are stationary at the first-difference. Thus, the empirical analysis would proceed to next stage, the cointegration analysis.

Table 5 reports the empirical findings for the Engle-Granger (EG) test for cointegration. As findings in the table showed, the EG test rejected null hypothesis of no cointegration when GDP is dependent variable for all ten Asian countries, except Bangladesh, China and Myanmar. It means that there is cointegrating relationship between economic growth and financial development when economic growth is considered as dependent variables. In other words, there would be long-run effect of financial development on economic growth. Similarly, the EG test rejected null hypothesis of no cointegration when FID is dependent variable for all ten Asian countries. It means that there is cointegrating relationship between financial development and economic growth when financial development is considered as dependent variables. In other words, there would be long-run effect of economic growth on financial development.

| Country |

GDP Dependent variable |

FIN Dependent variable |

| Bangladesh | -1.384 | -1.685* |

| China | -1.595 | -2.696*** |

| India | -2.356** | -1.700* |

| Japan | -1.611* | -2.030** |

| Korea | -2.995*** | -2.566** |

| Myanmar | -1.296 | -2.103** |

| Malaysia | -2.208** | -2.376** |

| Pakistan | -2.603*** | -3.157*** |

| Philippines | -1.746* | -2.326** |

| Singapore | -2.005** | -2.616*** |

Note: * indicates significant at the 1 percent level, ** indicates significant at the 5 percent level, *** indicates significant at the 10 percent level, the critical values for 1 percent level, 5 percent level, and 10 percent level are -2.6, -1.9 and -1.6 respectively.

Table 6 reported the empirical findings from the cointegrating regression analysis. As the findings in the table indicated, the cointegrating regression analysis rejected the null hypothesis of no cointegrating relationship for Bangladesh, India, Japan and Malaysia, Pakistan when the financial development would have impact on the economic growth. The findings also indicated that the financial development would have beneficial effects on the economic growth in all these five countries, except Bangladesh.

Similarly, the cointegrating regression analysis also rejected the null hypothesis of no cointegrating relationship for these five countries, namely Bangladesh, India, Japan and Malaysia, Pakistan, when the economic growth would have impact on the financial development. The findings also indicated that the economic development would have beneficial effects on the financial development in all these five countries, except Bangladesh.

| Country | GDP Dependent variable | FIN Dependent variable | ||

| coefficient | t-statistic | Coefficient | t-statistic | |

| Bangladesh | -0.290*** | -6.206 | -1.561*** | -4.257 |

| China | -0.105 | -0.922 | -0.066 | -0.167 |

| India | 0.189*** | 4.400 | 2.064*** | 4.257 |

| Japan | 0.602*** | 13.254 | 1.360*** | 11.944 |

| Korea | -0.170 | -0.915 | -0.056 | -0.316 |

| Myanmar | -0.048 | -0.525 | -0.181 | -0.459 |

| Malaysia | 0.248*** | 5.403 | 2.252*** | 6.003 |

| Pakistan | 0.264*** | 4.564 | 1.500*** | 3.537 |

| Philippines | 0.097 | 1.374 | 0.528 | 1.055 |

| Singapore | -0.054 | -0.306 | 0.156 | 1.029 |

Note: * indicates significant at the 1 percent level, ** indicates significant at the 5 percent level, *** indicates significant at the 10 percent level

Table 7(a) reported the empirical findings from the vector error correction (VEC) analysis when the economic growth is dependent variable. As the findings in the table indicated, significant error correction terms are significant in all ten countries, except Myanmar and the Philippines. It means that there is a long run relationship between economic growth and financial development in Bangladesh, China, Japan, Korea, India, Malaysia, Pakistan and Singapore.

Furthermore, the differenced dependent variables are significant in all ten countries, except Bangladesh, India, Malaysia and Singapore. It means that lagged value of dependent variable would have a significant impact on the present value of dependent variable in the short-run in six countries, namely China, Japan, Korea, Myanmar, Pakistan and the Philippines. On the other hand, the differenced independent variables are not significant in all ten countries. It means that lagged value of independent variable would not have a significant impact on the present value of dependent variable in the short-run in all these ten countries.

Table 7(b) reported the empirical findings from the vector error correction (VEC) analysis when the financial development is dependent variable. As the findings in the table indicated, significant error correction terms are significant in five countries, namely Bangladesh, Myanmar, Pakistan, the Philippines and Singapore. It means that there is a long run relationship between economic growth and financial development in these countries. Furthermore, the differenced independent variables are significant in all ten countries, except Bangladesh, China, Korea and Myanmar. It means that lagged value of independent variable would have a significant impact on the present value of dependent variable in the short-run in six countries, namely India, Japan, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippines and Singapore. On the other hand, the differenced dependent variables are significant in four countries, namely Japan, Korea, Myanmar and the Philippines. It means that lagged value of dependent variable would have a significant impact on the present value of dependent variable in the short-run in all these four countries.

| Country | Error correction term | ΔGDP(-1) | ΔFIN(-1) |

| Bangladesh | 0.013*** | -0.248 | -0.026 |

| China | -0.008** | 0.640*** | 0.037 |

| India | -0.014*** | 0.080 | -0.053 |

| Japan | -0.027* | 0.495** | 0.139 |

| Korea | 0.015** | 0.509*** | 0.070 |

| Myanmar | -0.001 | 0.948** | -0.014 |

| Malaysia | -0.020*** | 0.236 | -0.018 |

| Pakistan | -0.003*** | 0.325* | 0.027 |

| Philippines | -0.004 | 0.702*** | -0.023 |

| Singapore | -0.025*** | 0.206 | -0.068 |

Note: * indicates significant at the 1 percent level, ** indicates significant at the 5 percent level, *** indicates significant at the 10 percent level

| Country | Error correction term | ΔGDP(-1) | ΔFIN(-1) |

| Bangladesh | 0.024* | -1.424 | 0.129 |

| China | -0.013 | -0.220 | 0.023 |

| India | 0.006 | 0.720** | 0.171 |

| Japan | 0.039 | 0.532** | 0.499*** |

| Korea | 0.013 | 0.180 | 0.273* |

| Myanmar | 0.127** | -0.963 | 0.268* |

| Malaysia | 0.017 | 0.987** | 0.160 |

| Pakistan | 0.011** | 1.633** | 0.066 |

| Philippines | 0.055** | 1.396** | 0.294* |

| Singapore | 0.023** | 0.943*** | 0.205 |

Note: * indicates significant at the 1 percent level, ** indicates significant at the 5 percent level, *** indicates significant at the 10 percent level.

Table 8 reported empirical findings from the Granger causality test. As the findings in table indicated, the Granger causality test failed to reject the null hypothesis of causality from financial development to economic growth in all ten countries, except Singapore. In other words. Financial development contributed to stimulate economic growth in only the country. On the other hand, the Granger causality test failed to reject the null hypothesis of causality from economic growth to financial development in all ten countries, except China, Pakistan and Singapore. In other words. rapid economic growth contributed to financial development in these three countries.

| Country | FIN causes GDP | GDP causes FIN |

| Bangladesh | 0.149 | 0.102 |

| China | 0.343 | 4.632** |

| India | 0.500 | 1.548 |

| Japan | 0.800 | 0.105 |

| Korea | 0.703 | 1.843 |

| Myanmar | 0.159 | 2.811 |

| Malaysia | 0.033 | 0.539 |

| Pakistan | 1.290 | 3.699* |

| Philippines | 0.646 | 2.304 |

| Singapore | 3.201* | 5.390** |

Note: * indicates significant at the 1 percent level, ** indicates significant at the 5 percent level

In short, the empirical findings on the finance-growth nexus indicate some positive impact of financial sector on economic growth in Asian countries. These findings are in line with some period research (Jung, 1986; Wang, 1999, Ismihan et al., 2016; Slesman et al., 2019; Appiah‐Otoo and Song, 2022). It means that current study confirmed the expected outcome of current research that there is beneficial linkage between finance and economic growth. In other words, current study offer additional empirical proof to explain the positive role of financial sector in the economic growth process.

Conclusion

There is a certain agreement that financial sector has played an important role to stimulate economic growth. However, previous empirical analyses focused on America and European countries. There is still lack of systematic empirical analysis to examine the relationship between economic growth and financial development in the context of Asian countries. This study aims to fill this research gap by using the systematic econometric analysis, such as unit root test, the cointegration test, the cointegrating regression analysis, the vector error correction analysis and the Granger causality analysis.

The empirical findings indicate two main features of the finance-growth nexus in Asia. Firstly, the cointegration test, cointegrating regression and the vector error correction analysis clearly indicated that there is a significant relationship between financial development and economic growth in Asia. These findings confirmed the beneficial role of financial sector to stimulate economic growth in Asia. Secondly, the causality test indicates that the financial sector does not seem to cause economic growth in Asia. However, economic growth does cause financial development.

To conclude, the current study detected the important role of the financial sector to stimulate economic growth in Asian countries. Thus, the main policy implication of current study is that policymakers in the region should pay more due attention to the importance of financial sector. They may consider to use appropriate economic policies to provide more opportunities for financial sector to play more significant role in the process of economic growth in the region.

The main limitation of this study is the lack of sufficiently long time-series data. Future research may use quarterly data for the empirical analysis and may also use some systematic diagnostic test to examine the robustness of empirical findings. Other future research could use the panel data method to examine the relationship between economic growth and financial development in Asia. Researchers may also take account of the impact of the Asian economic crisis on the relationship between financial development and economic growth in for future research. These studies could contribute to offer important insights on the finance-growth nexus in the context of Asian economy.

References

Agbetsiafa, D. (2004). The finance growth nexus: evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Savings and Development, 28(3), 271–288.

Appiah‐Otoo, I., & Song, N. (2022). Finance‐growth nexus: New insight from Ghana. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 27(3), 2682–2723.

Chang, S. H., & Huang, L. C. (2010). The nexus of finance and GDP growth in Japan: Do real interest rates matter?. Japan and the World Economy, 22(4), 235–242.

Dal Colle, A. (2011). Finance–growth nexus: does causality withstand financial liberalization? Evidence from cointegrated VAR. Empirical Economics, 41(1), 127–154.

Dickens, C. (2006). A Christmas carol and other Christmas books. OUP Oxford.

Dickey, D. A. & Fuller, W. A. (1979). Distribution of the Estimators for Autoregressive Time Series with a Unit Root. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74 (366), 427–431.

Domar, E. (1946). Capital Expansion, Rate of Growth, and Employment. Econometrica. 14 (2), 137–147.

Engle, R.F. & Granger, C.W.J. (1987). Co-integration and error correction: Representation, estimation and testing. Econometrica. 55(2), 251–276

Fry, M. J. (1995). Financial Development in Asia: some analytical issues. Asian-Pacific Economic Literature, 9(1), 40–57.

Furuoka, F. (2015). Financial development and energy consumption: Evidence from a heterogeneous panel of Asian countries. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 52, 430–444.

Furuoka, F. (2016). Natural gas consumption and economic development in China and Japan: An empirical examination of the Asian context. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 56, 100–115.

Furuoka, F. (2017). Renewable electricity consumption and economic development: New findings from the Baltic countries. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 71, 450–463.

Hahn, F. R. (2005). Finance–Growth Nexus and the P‐bias: Evidence from OECD Countries. Economic Notes, 34(1), 113–126.

Haini, H. (2021). Financial access and the finance–growth nexus: evidence from developing economies. International Journal of Social Economics.48(5), 693–708

Harrod, R. F. (1939). An Essay in Dynamic Theory. The Economic Journal, 49(193), 14–33.

Granger, C. W. J. (1969). Investigating Causal Relations by Econometric Models and Cross-spectral Methods. Econometrica, 37(3), 424–438

Ismihan, M., Dinçergök, B., & Cilasun, S. M. (2017). Revisiting the finance–growth nexus: the Turkish case, 1980–2010. Applied Economics, 49(18), 1737–1750.

Iwasaki, I. (2022). The finance-growth nexus in Latin America and the Caribbean: A meta-analytic perspective. World Development, 149, 105692.

Jung, W. S. (1986). Financial development and economic growth: international evidence. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 34(2), 333–346.

King, R. G., & Levine, R. (1992). Financial Indicators and Growth in a Cross Section of Countries (Vol. 819). World Bank Publications.

Mathieson, D. J. (1980). Financial reform and stabilization policy in a developing economy. Journal of Development Economics, 7(3), 359–395.

Ozturk, I. (2008). Financial development and economic growth: Evidence from Turkey. Applied Econometrics and International Development, 8(1), 84–98.

Sims, C. (1980). Macroeconomics and Reality. Econometrica, 48(1), 1–48.

Slesman, L., Baharumshah, A. Z., & Azman-Saini, W. N. W. (2019). Political institutions and finance-growth nexus in emerging markets and developing countries: A tale of one threshold. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 72, 80–100.

Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70(1) ,65–94.

Stock, J. H., & Watson, M. W. (1993). A simple estimator of cointegrating vectors in higher order integrated systems. Econometrica, 81(4), 783–820.

Pagano, M. (1993). Financial markets and growth: an overview. European Economic Review, 37(2-3), 613–622.

Patrick, H. T. (1966). Financial development and economic growth in underdeveloped countries. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 14(2), 174–189.

Valverde, S. C., & Fernández, F. R. (2004). The finance-growth nexus: a regional perspective. European Urban and Regional Studies, 11(4), 339–354.

Wang, E. C. (1999). A production function approach for analysing the finance-growth nexus: the evidence from Taiwan. Journal of Asian Economics, 10(2), 319–328.

World Bank (2022). World Development Indicators. [accessed on 16 February 2022]. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

Last Update: 27/07/2023