Beijing has long been anxious about the popularity of the Dalai Lama, and Tibet remains a principal source of international vulnerability for the Peoples Republic of China. After the Dalai Lama relinquished political responsibilities in 2011, the position of Sikyong, considered president of the Central Tibet Administration, the India-based Tibetan government-in-exile, has become another sore point.

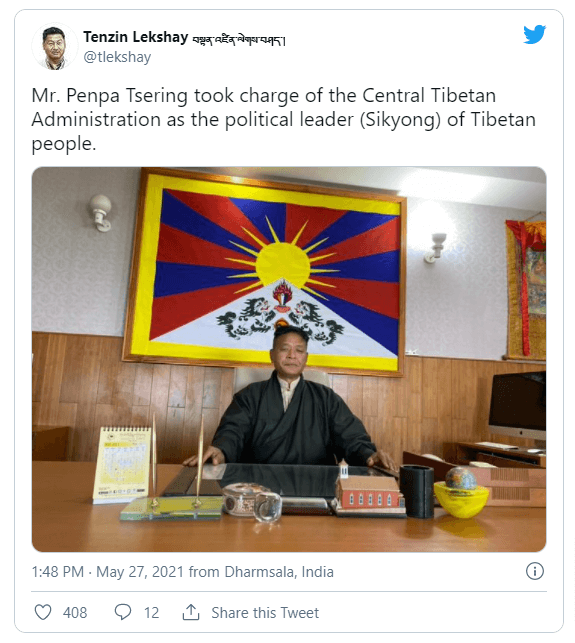

A swearing-in ceremony of the newest Sikyong, Penpa Tsering, took place on 27 May, following two rounds of elections, held in January and April. More than 64,000 Tibetans from 26 countries cast their votes.

But ever conscious of the contest over the narrative, China made a point to issue its latest White Paper on Tibet to coincide with the elections, if only as a rhetorical attempt to consolidate and justify its claims. The White Paper, “Tibet Since 1951: Liberation, Development and Prosperity”, built on earlier versions, including in 2019, “Democratic Reforms in Tibet – Sixty Years On”, and the 2018 paper “Ecological Progress on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau”, the last an effort to counter international concerns about environmental degradation in the region.

The use of terms such as “peaceful liberation”, “development” and “prosperity” mark China’s attempt to establish the legitimacy of its authority over Tibet and justify its activities, including efforts to change the demography with rapid “Hanisation” of Tibet. This propaganda exercise betrays China’s lack of confidence even after 70 years. Although Beijing’s grip on the region is arguably stronger than it is in Xinjiang or Hong Kong, China worries about the support Tibetans have garnered for their movement. This is especially due to political backing provided from within the US to the Tibetan independence cause.

China is mindful that the status quo vis-à-vis the Tibetan government-in-exile is in place only while the present Dalai Lama is alive. While a number of countries have accepted Beijing’s “one China policy” demands, including on Tibet, that could quickly change. India’s recent spate of tensions with China, for example, stretching from the Doklam standoff in 2017 to clashes in the Himalayas last year, could be the harbinger of a shift.

American attitudes will be a bellwether. In 2020, the US Congress passed the Tibet Policy and Support Act (amending the 2002 Tibet Policy Act), demanding that China allow the US to establish a consulate in Lhasa. The US also supports the Dalai Lama’s sole right to select his successor. Former Sikyong Lobsang Sangay played an instrumental role in elevating the ties between the US and the Tibetan government-in-exile, visiting the White House in the final days of the Trump administration, the first time in 60 years such an exchange had taken place. But the US has not changed its policy that considers Tibet a part of China, which certainly comforts Beijing.

New Sikyong Penpa Tsering has pledged to continue pursuing the Chinese leadership to reinitiate the Sino-Tibetan dialogue and a “middle-way approach”. But he must be mindful that this established style is not in sync with the growing desire for independence among the Tibetan youth, or greater willingness in the US to offer financial and political support on an issue that is sensitive to Beijing.

China also sees the risk that the Tibetan government-in-exile could become more vocal, especially in attempts to draw attention to human rights violations. The growing US–China rivalry is changing the dynamics of the contest over Tibet. The latest White Paper from China should be read with that perspective in mind.

This article was first published in The Interpreter

Last Update: 11/11/2021