AEI-Insights: An International Journal of Asia-Europe Relations

ISSN: 2289-800X, Vol. 9, Issue 1, July 2023

DOI: https://doi.org/10.37353/aei-insights.vol9.issue1.1

Zane Šime

Department of Historical and Classical Studies

Norwegian University of Science and Technology

zane.sime@ntnu.no

Abstract

The existing body of literature on educational diplomacy and talent flows should be broadened with insights from understudied countries and geographic areas. Such a research direction is relevant to the balanced mobility considerations included in the Asia-Europe Meeting Education Process. This study concerns the increasing inflow of students in Latvia from Asia. It is motivated by the growing interest across the Asia-Europe Meeting partner countries to analyse international student pathways. Compared to the world’s leading higher education destinations, Latvia does not operate a wealth of resources for educational diplomacy. However, since educational diplomacy is a relatively novel term in the Latvian setting, the impact of Latvia’s granted scholarships and the overall pool of international students welcomed in Latvia remains an understudied area of the general international interconnectedness of the country with Asia and beyond. It is a promising area for further exploration of how ties fostered through higher education support the Latvian diplomatic aspirations spanning well beyond the rather narrow academic focus on the talent flows across the higher education destinations of the Baltic Sea Region, as well as policy and academic attention paid to the Latvian diaspora worldwide. The shifting student pathways and collaborative networks invite paying continuous attention to the evolving interconnections across Europe and Asia.

Keywords: educational diplomacy, higher education, student mobility, Latvia, Asia-Europe Meeting

Introduction

Student flows are among the widely debated topics of the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM). As the subsequent sections of the article elaborate, ASEM regularly discusses the prevailing destinations of internationally mobile students with an overarching interest in promoting balanced mobility. The increasing number of students from Asia enrolling in Latvian higher education institutions is an example that deserves more attention. Based on the latest thinking relevant to educational diplomacy and how it fits in a broader context of diplomacy studies, the article explores what new dimensions such international pathways of individuals could bring to Latvian diplomatic aspirations.

The article explores what the potential educational diplomacy resources are of Latvia. The aim is to explore educational diplomacy as an emerging thematic area of scholarly enquiry and a potential new dimension of the overall corpus of Latvian diplomatic ambitions and objectives. To answer this question, this article taps into the often-adopted core-periphery dichotomies. The distinction between student-sending countries and receiving hubs is witnessed in the literature examining international talent flows, especially regarding the prevailing focus on Latvia as a source of human capital outflow. The multilateral framework of ASEM is brought into perspective to highlight how the international talent pool hosted by Latvia sets a favourable context for the overarching goals of ASEM to foster ties between Asia and Europe.

The first part introduces educational diplomacy in a broader context of several strands of diplomatic studies. It outlines significant threads of scholarly enquiry related to the diplomatic dimensions of international higher education pathways. The second part elaborates on ASEM, its earlier intellectual footprint in Latvia, and Asia-Europe dynamics in Latvia that go beyond the ASEM-tagged initiatives. The third part indicates a statistical background and analytic considerations on the international student flows coming to Latvia and the intricacies associated with the existing data sets. The fourth part reviews the core-periphery dichotomies of talent flows affecting Latvia. Additionally, the fourth part pinpoints some understudied aspects. The concluding part sums up key findings.

Contextualising Educational Diplomacy

Diplomacy encapsulates how states and various other entities represent themselves (Hare, 2023, 6). Educational diplomacy explores the role of students, teachers, and exchange programmes in public diplomacy (Bislev, 2017, 83-84). It “utilizes education as a means to accomplish foreign policy goals such as the cultivation of goodwill and the shifting of perceptions of the host nation to facilitate improved foreign relations with other countries” (Yousaf, Fan and Laber, 2020, 166). Educational diplomacy emanates from the study of international engagements of American higher education institutions (Mäkinen, 2016, 184). Universities and individual academics are distinguished as highly effective non-governmental public diplomacy agents (Riordan, 2005, 191). University alumni have been identified among those parts of society that have relatively recently won policy and scholarly attention (Huijgh, 2013, 68). This article might be considered one of such examples more, focused on the student international pathways and the acquisition of academic degrees, training experience, ties and familiarity with other countries than the native one.

Cultural diplomacy is a vaster area of diplomacy studies. It incorporates education, universities and exchange programmes as components of a broader thematic spectrum that comprises science, technology, arts, traditional mass media, the film industry and sport (Krenn, 2017, 40, 124, 135; Parrish, 2022, 1520-1521). In such a constellation, cultural diplomacy is part of a broader realm of public diplomacy (Gienow-Hecht and Donfried, 2010, 14). Thereby, educational diplomacy is nested within cultural diplomacy and an even more general framework of public diplomacy. To attest to the depth and richness of these areas of scholarly enquiry, it should be added that each of these diplomacies has its own “information battles”, manner to develop and maintain “stores of goodwill”, as well as “gift” exchange traditions and inventions that surpass the scope of this article (Cull, 2022, 18-19; Naddeo and Matsunaga, 2022, 121).

Furthermore, drawing attention to these three thematic scopes of diplomacy studies is based on the observation that cultural diplomacy glosses over the role of education, universities and exchange programmes (Carta and Higgott, 2021). Recent studies show that cultural diplomacy does not go into the functional heterogeneity of cultural centres established worldwide by various countries in terms of discerning and examining in more specific terms their public outreach, educational, training and advanced research functions (Carta and Badillo, 2021; Higgott and Proud, 2021; Macdonald and Vlaeminck, 2021; Trobbiani and Pavón-Guinea, 2021). Language lessons, three cycles of higher education and cultural events each have their unique characteristics and value as diplomatic resources. At the same time, educational diplomacy adds more profundity and draws attention to various far-reaching considerations related to higher education and research institutions, exchange programmes and the experiences of students.

Studies revolving around the United States (US) prove that universities are valuable venues for the individual and collective exploration of what a nation, region and city stand for in complex episodes of history (Guerlain, 2004), its public engagement (Weerts and Freed, 2016) and what values it aspires to instil in its academic staff, students and other audiences exposed to its intellectual routines and training offer (Bouchet-Sala, 2004; Robert, 2004; Barrier, Quéré and Vanneuville, 2019). Individual institutions are said to increasingly act beyond the traditional notions of state sovereignty in pursuing specific strategies and motivations weaved within a broader “cobweb of interests” (McGill Peterson, 2014, 3; Surowiec and Manor, 2021, ix). Educational diplomacy allows drawing upon a more detailed account than the concise notes on former efforts to attract more students from abroad to pursue a more cosmopolitan standing of a university (Schroth, 2008, 195). The educational diplomacy and literature relevant to its core thinking draw more detailed findings on universities and other types of advanced study centres as considerable resources for strengthening specific goals of foreign policy and diplomatic aspirations.

The observed small renaissance of diplomacy studies comes with some perplexities (Weisbrode, 2023, 37). The blurred boundaries between educational diplomacy and other strands of enquiry characterising diplomacy studies cannot be explained only by public diplomacy having diverse understandings across the full spectrum of contributing authors (Arceneaux, 2021, 10; Walker, Fitzpatrick and Wang, 2022). Additionally, educational diplomacy has a hardly discernible border or, in other words, very tightly knit interlinks with science diplomacy. Both applaud the potential of universities and academic staff. Science diplomacy publications ornate universities with their own foreign policies (Gast, 2021) and refer to them as “engines of global collaboration” (Lee et al., 2021). Educational diplomacy, science diplomacy and connectivity studies are interested in people-to-people ties (Suttmeier, 2010, 25; Becker et al., 2021; Lyons, Lips and Obonyo, 2021). This article is too concise to elaborate on further nuances of this complex interlink between educational and science diplomacies1. Therefore, these short remarks aim at introducing the reader to this challenging scholarly nuance (Sabzalieva et al., 2021, 151; Knight, 2023) and then turn toward the details of the topic of this article by borrowing insights from all the adjacent and thematically close areas of scholarly enquiry. What remains to be added is that other countries have shown receptiveness to this line of thinking, though with their distinct approaches to educational diplomacy, planning and a constellation of instruments.

What a significant number of the earlier cited research have in common is a reference to soft power and new public diplomacy. The logic of soft power (Nye, 2017) is known as a basic assumption of ‘attractive’ power among new public diplomacy scholars (Hocking, 2005, 33). These are often referenced building blocks in educational resources elaborating on “a soft power arms race” (Ohnesorge, 2020, 145, 299) and case studies that seek to advance the overall thinking on educational and cultural diplomacies (Trilokekar, 2010; Krenn, 2017, 15; Ramdas, 2021). The diversity of actors is brought into the picture of national brand and interest representation (Hemery, 2005, 203; Gienow-Hecht, 2019, 770). Higher education as an area of “policy competence” (Drezner, 2020, 9), and universities as an embodiment of brilliance (Patalakh, 2017, 153) and hosts of foreign-born faculty staff (Ertem-Eray and Ki, 2022, 21), are positioned as promising means for a country to improve understanding among foreigners of its goals and the value of an internationally joined-up approach in reaching its pursued milestones. Educational exchanges are classified as part of the active approach to soft power, meaning these are instruments for the purposeful dissemination of an actor’s soft power resources on an international scale (Ohnesorge, 2020, 88, 204). In French-speaking circles, ‘diplomacy of influence’ (la diplomatie d’influence) is a term that often echoes ideas captured by educational diplomacy and soft power literature (Billion and Insel, 2013; Delcorde, 2019; Martel, 2013; Tenzer, 2013).

Subsequent examples bring more country-specific and multilateral insights that span beyond the emblematic inception of the Fulbright Programme, and the US Institute of International Education supported by the Carnegie Endowment, grants for educational development abroad issued by the Rockefeller Foundation, as well as long-term impacts on institutions and individual career pathways shaped by the Ford Foundation International Fellowships Programme and institutional grants (Poupeau and Discepolo, 2002, 46; Gienow-Hecht and Donfried, 2010, 15; Guilhot, 2017; Krenn, 2017, 54, 80; Paddayya, 2018, 110; Campbell, Lavallee and Kelly-Weber, 2021; Kilias, 2021). All in all, the study of educational diplomacy benefits from various national contexts and worldwide developments, including the attention paid to how these instruments leave imprints not only on individual academic and professional pathways but also are echoed in bilateral and multilateral settings among countries. It shows the vast resources at the disposal of countries to pursue contextually rich and ambitious educational diplomacy. Likewise, it deserves attention as an extensive repository of lessons learnt, which might help such countries as Latvia navigate this segment of novel diplomacies.

Australia is another Anglo-Saxon example of a significant international study destination addressed in the existing body of educational diplomacy. Several decades have passed since the inception of Australia’s thinking on the role of higher education as a significant component of the country’s international standing (Byrne and Hall, 2013; McConachie, 2019). Overall, it seems to share notions of an agency similar to the subsequently mentioned Chinese example. Students, as future professionals, maintain an imbrication between the institutions they graduate from and work for (Carter, 2015, 484).

The shifting international geopolitical landscape and emerging points of gravity (Gharlegi, 2019; Müller et al., 2021) are mirrored in the dynamics of educational diplomacy studies. The Chinese official positioning of students being considered as people-to-people or brand ambassadors (Custer et al., 2019), various internationalisation measures (Shen, 2018), and its achievement in 2015 of becoming the third internationally leading student destination have generated research interest (Huang, Jin and Li, 2016, 41; Wu, 2019, 620; Yousaf, Fan and Laber, 2020, 166; Mulvey, 2021). Moreover, increased offers of China-funded scholarships and rising investments in research have not gone unnoticed (Johnson et al., 2021, 17, 67). Students are not the sole element of the unique brand of educational diplomacy crafted by China (McGill Peterson, 2014, 2-3; Wang, 2016). The Confucius Institutes, with their various spill-over effects, constitute another component (Yang, 2010, 241; Gazeau-Secret, 2013, 105; Gallarotti and Sautedé, 2017, 184-185; Brazys and Dukalskis, 2019b; Kauppi, 2019, 745; Huang, 2021). Further, growing engagement across Africa shows the dynamic South-South ties (King, 2014). Besides BRICS collaboration in physics and astronomy guided by mega-science (Kahn and Puri, 2017), the BRICS Universities League is seen as a means for China to extend its public diplomacy (Lei and Sordia, 2017). This is a brief overview of the overall scholarly enquiry into various strands of Chinese educational diplomacy, not an exhaustive summary.

Due to the high hopes associated with higher education and its produced future ambassadors of shared values (Rasgotra, 2005; Ravi, 2014; Amaresh, 2020), educational diplomacy is a term that is also linked with studies exploring regionalism in higher education and research domains, with the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation as one of such examples spanning well beyond the South Asian University (Nair, 2013, 38; Pandey, 2018, 14). In the South Asian setting, interlinks between educational diplomacy and people-to-people contacts are established (Pandey, 2018, 14). Student ambassadorship qualities of internationally oriented talents are echoed elsewhere in India (Kochhar, 2021; Singai and K, 2021). It provides a background for a broader exploration of such interconnections across Asia and Europe.

Education is one of the components of Russian public diplomacy (Tsvetkova and Rushchin, 2021, 55). Russia is among the leading study destinations for students from the Commonwealth of Independent States (Vinokurov, Libman and Pereboyev, 2015, 14). ‘Exchange diplomacy’—recognised for being “the most two way form of public diplomacy” (Ohnesorge, 2020, 156)—is a term that researchers interested in exploring the Russian context have used to analyse the role of short-term mobility of students in fostering ties among countries (Mäkinen, 2016, 183). Over the past years, Russia’s higher education institutions have sought to attract more students from abroad to “raise their revenues and their status” (Fominykh, 2020, 120). Another noteworthy public diplomacy resource are the Russian Centres for Science and Culture established across the world (Fominykh, 2020, 129).

South Korea is among Asia’s emerging regional higher education hubs (Istad et al., 2021, 3). “Korean foreign aid has been directed towards building scientific and technical schools/universities, with some addressing capacity building.” (Moon and Shin, 2016, 825) The Global Korea Scholarship programme attracts research attention to exploring its public diplomacy performance and deficiencies in fostering ties with other countries through study experience (Ayhan and Gouda, 2021; Hong, Jeon and Ayhan, 2021). Since 2007, another notable public diplomacy resource is the King Sejong Institutes established across the world to promote cultural awareness and Korean language learning opportunities (Eom, Kim, Roh and Lee, 2019; Lien, Tand and Zuloaga, 2022, 10-11; Picciau, 2016, 97).

The funding programmes of the European Union (EU) tailored for academic mobility, higher-education networking, research, and capacity-building—for example, Erasmus(+) and EU Framework Programmes—have benefited from some preliminary attention demonstrated by the researchers keen on examining the EU public and educational diplomacies with an empirical focus on the Eastern Neighbourhood (Chaban and Elgström, 2020; Bobotsi, 2021; Piros and Koops, 2021), the US (Thiel, 2023) and the international resonance at large (Chamlian, 2019; Fanoulis and Revelas, 2023, 55). Jean Monnet Centres of Excellence are locally rooted hubs of EU studies established across the world. “EU Support to Higher Education in the ASEAN Region” (EU-SHARE) is an EU-funded project example of how the Union attempts to assist Asia in identifying the latest trends in higher education. EU-SHARE helped pinpoint challenges and opportunities worth further exploration, such as the internationally growing attractiveness of the Singaporean higher education offer buttressed by the Singaporean scholarship offer to students from the member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) (Chong, 2022, 16-17; Lim, Anabo, Phan, Elepaño and Kuntamarat, 2023, 34).

Besides, what remains outside the scope of the primary considerations embraced by the reviewed writers on educational diplomacy are certain strains that internationalisation and talent attraction have put on some academic staff (van Houtum and van Uden, 2020; Nicholls, Henry and Dennis, 2021). This seems to be a so-to-say domestic or science communication backstage (Davies, 2021, 211). It might not apply to all national and regional contexts where educational diplomacy is discussed. The administrative challenges are not brought into the picture when educational diplomacy's advantages and cherished potential are articulated.

Latvia Within and Beyond the Asia-Europe Meeting

ASEM was created in 1996 as an informal platform for dialogue and cooperation between Asia and Europe (Badel, 2016, 60). Its overarching goals are fostering political consultations, the advancement of economic ties and responses to global challenges, often themed under the cross-cutting focus on connectivity (Hellendorff, 2016; Tertrais, 2016, 139; Lechervy, 2016, 119, 123). The history of ASEM, its founding fathers and the logic of its inception, as well as the development of certain domain-specific strands, are widely documented and addressed from diverse angles (Camroux, 2006; Hwee, 2006; Robertson, 2008; Gaens et al., 2015; Angress and Wuttig, 2018; Gaens and Khandekar, 2018; ASEM Education Secretariat, 2019). This article does not strive for a mere repetitiveness of earlier accomplishments and observations within a broader context of the dynamics of formal and informal international organisations (Capannelli, Lee and Petri, 2009, 27; Stone and Moloney, 2019, 1-2). Instead, this article seeks to shed light on understudied dimensions that implicitly contribute to fostering ties and enhancing mutual familiarity across Europe and Asia. Following the ASEM Education 2030 Strategy Paper (ASEM, 2021, 7), higher education is a valuable means for increasing the overall awareness among young generations about the intricacies of political dialogue, economic cooperation and internationally resonating challenges. Asia-Europe ties developed in Latvia remain understudied. Latvia-based Asia-Europe interactions thus deserve more scholarly attention.

The ASEM Education Process defines the essence of the forum’s role in higher education. Established in 2008 during a ministerial meeting held in Berlin (Germany), the ASEM Education Process supports collaboration in the education domain within ASEM through political interactions on political and senior official levels (Munusamy and Hashim, 2020, 471). Four thematic priorities of the ASEM Education Process are quality assurance and recognition, engaging business and industry in education, balanced mobility and lifelong learning, including technical and vocational education and training. Two transversal priorities of this process are digitalisation and sustainable development. "The four strategic objectives outlined in the ASEM Education Strategy 2030 […] provide the basis for cooperation over" this "decade: 1) enhancing connectivity between Asia and Europe by boosting inclusive and balanced mobility and exchanges; 2) promoting lifelong learning, including technical and vocational education and training […]; 3) fostering the development of skills and competences; and 4) creating more transparency and mutual understanding on recognition, validation and quality assurance." (ASEMME8, 2021, 2) This article addresses in more depth one of the thematic priorities of the ASEM Education Process and the strategic objective of the ASEM Education Strategy—balanced mobility— by exploring in greater detail the pool of Asian talent hosted by one understudied ASEM partner country. However, it does so by offering some relevant insight to better understand the talent flows that contribute to the rest of the five thematic strands of the ASEM Education Process and the strategic objectives of the ASEM Education Strategy.

The 2nd ASEM Education Ministers’ Meeting facilitated the establishment of the rotating secretariat for the ASEM Education Process (Munusamy and Hashim, 2020, 474). This administrative support body facilitates convening meetings associated with the ASEM Education Process. Various ASEM partner countries host the secretariat temporarily. Latvia has never hosted this secretariat.

Several ASEM initiatives effect Latvian higher education and research. Besides regular participation in various ASEM formats, in 2015, during its EU Presidency, Latvia hosted the 5th ASEM Education Ministers’ Meeting (ASEMME5). The internationalisation process of Latvian higher education does not prioritise the ASEM Education Process. Nevertheless, the ASEM Education Process provides various opportunities for students and researchers of Latvian origin or Latvian institutional affiliation to be eligible for participation. For example, the higher education staff of institutions in Latvia participated in and contributed academic publications to the ASEM Lifelong Learning Hub (see Birziņa et al., 2012; Degueldre and Reynders, 2021, 32). Since ASEM Duo Fellowships are not administered nationally by each ASEM participating country, an overview of students enrolled in Latvian universities who participated in past fellowships is not included in this article. The ASEM Summer Schools is another example of ASEM-endorsed international study opportunities for students. The ASEM Summer School 2022 “Civic Engagement and Sustainable Development” hosted online by the Asia-Europe Institute of the University of Malaya (Malaysia) and Aschaffenburg University of Applied Sciences (Germany) attested to the success in promoting a more balanced virtual mobility of students, researchers and academics between Asia and Europe.

However, ASEM, ASEM-endorsed initiatives or the Asia-Europe Foundation activities (see Le Thu, 2014, for a concise overview) do not capture the complete picture of interactions across Europe and Asia. Therefore, this article builds on other country specific case studies of the role of higher education and advanced training in promoting closer ties between Asia and Europe, such as Vietnam (Quang Minh, 2016). This article looks at the potential of the educational diplomacy of Latvia towards Asia without restricting the focus solely to the ASEM explicit developments and ASEM-tagged geographical and online mobility patterns.

Unlike some of the main study destinations mentioned in the earlier sections of the literature review, Latvia does not operate a wealth of resources that would correspond to the educational diplomacy study. Latvia does not fund major cultural or research institutes abroad. Information and study centres established in Chennai (India) in 2014 and Colombo (Sri Lanka) in 2016 are exceptional examples of university-led outposts that facilitate access to information about higher education in Latvia.

On an ad hoc basis, the embassies of Latvia host either introductory sessions to inform diverse audiences about study opportunities in Latvia or informative and networking occasions tailored to researchers in the advanced and senior stages of their academic careers. International short-term schools for all cycles of higher education students are another form of introduction to the teaching and research offered in Latvia. Higher education institutions in Latvia regularly organise their own schools or host events anchored in supranational and transnational initiatives, such as those funded by various EU programmes, Summer Universities of the Council of the Baltic Sea States, Nordplus programmes etc.

Similarly to some of the previously mentioned countries, Latvia offers study and research scholarships to students from more than 40 countries. Besides scholarships funded by Latvia, higher education and research facilitation programmes sponsored by other countries, multilateral forums or EU programmes enable many foreign students and researchers to pursue a specific academic stage in Latvia. The growing number of international students enrolling in Latvian higher education institutions is the central element and the most promising area for a study of the educational diplomacy potential of Latvia. It brings one more dynamic example to the existing literature on the shifting landscape of international student mobility and research encounters.

This composition of institutional, national, macro-regional, supranational and international initiatives demonstrates that Latvia's implicit educational diplomacy has evolved against the country’s participation in different international, multilateral and bilateral frameworks, each with its distinct goals, logic and means of implementation. Interactions across Asia and Europe are only one of its dimensions. Most importantly, not all Asia-Europe students' mobilities associated with Latvia are pursued under one programme or initiative. Thus, these educational pathways do not follow the same goals. Overall, a multitude of factors come into play in how the talent pool from Asia in Latvia is formed and evolves over time.

However, one item that might be common to these international pursuits is the increased administrative workload on the Latvian public authorities responsible for migration and welcoming higher education institutions. Among the brainstorming ideas to tackle this periodic increase of applications for visas and residency permits and the required investment of human resources to process these applications was to prolong the work hours of corresponding staff at public authorities and higher education institutions (Ministry of Science and Education, 2019). This periodic wave of heightened administrative workload is not a significant obstacle to the overall hosting of international students. In a broader context of various aspects discussed on the recent trends and prospects for the international standing of higher education in Latvia, this is one of many areas listed where there is room for improvement, not a cause of significant concern.

Latvia as an International Study Destination

Focus on higher education and the international exchanges that accompany it is chosen with a full appreciation of the recent research conclusions that “Europeans have rediscovered their enthusiasm for globalisation, including free trade and immigration” (Darvas, 2020, 26). Latvia is among these enthusiasts, with considerable attention turned towards “the open European space” (Lapiņa and Ščeulovs, 2014, 407) and the opportunities it offers both to Latvians and foreigners from across the globe.

Firstly, in roughly three decades, Latvia has experienced a breath-taking evolution of its higher education sector from being preoccupied with higher education as a domestic developmental tool (Auers, Rostoks and Smith, 2007, 16) to its study programmes becoming an attractive offer to students from various parts of the world. International outreach extends to helping Ukraine establish European Studies (Bērziņa, 2015, 25). The logic of technical assistance is also echoed in the earlier findings on the availability of higher education in Latvia to students from post-Soviet Eurasia (Chankseliani and Wells, 2019, 12). The Latvian Education Development Guidelines 2021-2027 confirm the country’s commitment to strategically prioritising internationalisation in higher education (Cabinet of Ministers, 2021, 46-47).

Researchers in Latvia have recognised globalisation as one of the key strategic drivers of higher education quality and outlined the role of the Bologna Process (Nikitina and Lapina, 2017, 57; Degtjarjova, Lapina and Freidenfelds, 2018, 392). From the perspective of a country with a projected shortage of highly skilled labour (Biagi, Castaño Muñoz and Di Pietro, 2020, 11, 16), international competition for students is also among the considerations guiding higher education institutions in their pursuit of attracting applicants (Melnikova and Zaščerinska, 2016, 101; Rika, Roze and Sennikova, 2016, 422). Personal experiences of such international competition is documented in the academic literature on the Latvian diaspora (Lulle and Buzinska, 2017; Kaša, 2019). European countries' indicators show a considerable outflow of young, highly skilled talent from Latvia (Rocca, 2020, 12). While maintaining continuous research attention towards the attractiveness of the higher education offer among residents of Latvia (for example, Tarvid, 2014), small-scale cross-country comparisons with nearby countries facilitate sporadic contextualisation of certain aspects of student performance, interests and academic pathways as learners and future professionals, workforce of a knowledge economy (Kirch, 2018). Young, highly skilled individuals of Latvian origin, are among the groups that have attracted the attention of researchers in migration studies (Aksakal and Schmidt, 2019; Emilsson and Mozetič, 2019; Lulle and Bankovska, 2019). Their findings offer further insight into the multi-faceted talent flows across the Baltic Sea Region, and diverse considerations drive each student and young professional. These findings attest to how densely Latvia is intervowen in the collaborative and interactive patterns of the Baltic Sea Region.

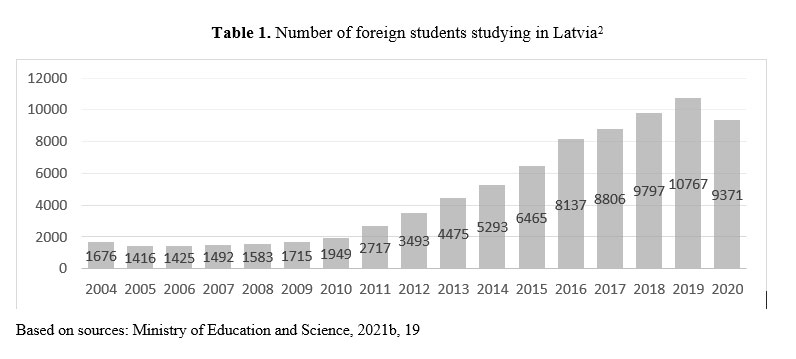

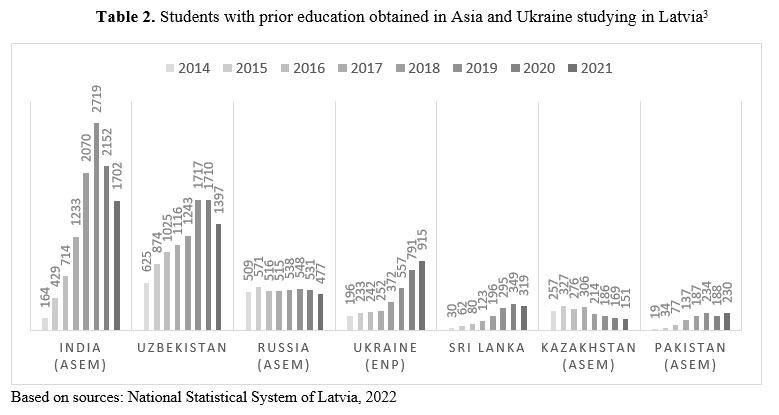

Secondly, two parallel dynamics are noteworthy. Since Latvia’s accession to the EU and joining ASEM in 2004, many foreign students have chosen Latvian higher education institutions as their study destination (Table 1). This upward dynamic is coupled with an increasing number of individuals from Asia studying in Latvia. These students have obtained previous education in another country than Latvia. Due to their interest in acquiring higher education, they might be considered the potential “brand-builders” of Latvian institutions (Mazais, Lapiņa and Liepiņa, 2012, 525). Over the most recent years, the most widely represented countries have been India, Uzbekistan and Russia (Roga, Lapiņa and Müürsepp, 2015, 929; Ministry of Education and Science, 2021, 19).

Correspondingly, Table 2 of the rather recent foreign student dynamics (2014-2021) depicts that ASEM participating countries are not the only ones that top the Asian list of the most widely represented countries among the mobile individuals pursuing their studies in Latvia. Such a broader contextualisation beyond the participating entities of ASEM clarifies that the upward trend of student arrivals to Latvia is not a special characteristic of the ASEM participating countries. Additionally, it demonstrates the much larger volume of talent flows that occur outside of the framework of ASEM-tagged initiatives. Rather, it mirrors the general rise of international mobility of students world-wide, including its echoes in the Latvia-specific context. An exceptional national case (located beyond Asia but) placed next to Asian examples in Table 2 is Ukraine. It is based on the earlier noted avid engagement of the EU with the Eastern Neighbourhood in higher education and academic domains, as well as Latvia’s contribution to the development of academic quality in Ukraine. Student inflows in Latvia with Ukrainian educational background helps contextualise the considerable proportion of student inflows formed by Asian countries.

While these might seem like tiny numbers of student inflow to larger and more populous countries, for Latvia—a country with a population of roughly two million and a pool of foreign students not reaching 11 000 individuals—those with a prior education from India form a considerable share. Overall, students choose a wide range of study programmes in Latvia. No specific thematic concentration is in overwhelming demand (Auers and Gubins, 2016, 6). For roughly half of the students from Asia, Latvia was the priority study destination (Apsite-Berina et al., 2020, 517). Even without displaying the allure of world-class universities (Sitnicki, 2018) and making no claims of soft power that is characteristic among the world’s most emblematic institutions, the Latvian higher education offer proves to be internationally competitive, not just some parts of it.

The statistics on students who learned elsewhere before their studies in Latvia indicate individuals who enrolled in a programme at a Latvian higher education institution to obtain an academic degree. Table 2 does not include statistics on exchange students, meaning students who pursue at Latvian higher education institutions short-term mobility of several weeks, an exchange semester, or several exchange semesters. Likewise, these statistics do not depict those students of foreign nationality who pursue consecutive two or three cycles of higher education studies in Latvia because they rest immobile in terms of their choice of country for higher education. Overall, Table 2 is a generalised starting point for an educational diplomacy study, not a fine-grained statistical picture. For example, it does not provide a clear view of students' citizenship, only where they have pursued their previous studies.

Nevertheless, none of the countries (except Russia) indicated in Table 2 are known as overwhelmingly popular destinations for degree-seeking Latvians. All in all, Table 2 is sufficient for further elaboration on why the current mobility trends are a good point for a departure to address the earlier expressed concerns about the future of ties across Europe and Asia.

Over the last two decades, both in Europe and Asia, concerns were voiced about the lack of interest among Asian students in pursuing their studies in Europe, opting for the US and Australia instead (Commission of the European Communities, 2001, 19-20; Picciau, 2016, 103; Rana et al., 2016, 86). Latvia can be taken as an example of how this student mobility gap is narrowing. The increasing numbers of students who have obtained their prior education in one of the countries in Asia and choose to pursue their next academic stage (or part of it) in Latvia demonstrate some progress. It provides some encouragement for cautious optimism. Having more students from Asia studying in Latvia contributes to the ASEM overarching goal of bringing Europe and Asia closer through daily encounters and study experiences among students. A closer look into other national statistics of EU member states would help to clarify whether Latvia faces a unique situation or there is room for some more widely shared optimism about Europe’s ability to address (to a certain degree) the earlier identified challenge. Of course, this observation does not address the more recent shift in attention towards balanced mobility in encouraging more European students to choose Asia as their study destination (Degueldre and Reynders, 2021, 94). This ASEM consideration is left outside of this article and deserves to be addressed separately.

This article shies away from providing very detailed prescriptions for the potential pathways to developing the Latvian approach to educational diplomacy due to the following considerations. The birds-eye-view approach adopted in this article acknowledges the challenge of distinguishing between the various implications that increased international student mobility might have on individual academic and professional career trajectories. While ASEM-endorsed initiatives strive for more balanced mobility of students, they cannot predefine the following steps a beneficiary might take in pursuing an individual path in the job market in the country of origin or elsewhere. The same complexity and unpredictability apply to the future life stages of foreign students hosted in Latvia. What choices a student makes after studies in Latvia and how that tallies with or diverges from the goals of balanced mobility, brain circulation or talent attraction, and workforce retention logic are not predefined, carved in stone, or subject to stringent regulation by public authorities. This uncertainty is an exciting and uncharted field for a more nuanced study of educational diplomacy, namely, how it unfolds in various national, macro-regional, and international contexts.

Shifting Notions of Latvia’s Centralities and Peripheries

This article broadens awareness about the newfound potential to foster closer ties between Asia and Europe beyond the encounters facilitated by the ASEM-tagged initiatives, such as the ASEM Fellowships and ASEM Summer Schools. Additionally, it brings some new perspectives on the international positioning of Latvia in various dynamics characterising the knowledge economy. Several earlier publications portray Latvia as a peripheral location through a one-sided focus on the diaspora of Latvia (King, Lulle and Buzinska, 2016; King et al., 2018). The Centre for Diaspora and Migration Research of the University of Latvia, the World Congress of Latvian Scientists and the World Latvian Economics and Innovations Forum are among the most visible Latvia-based hubs of expertise on the research potential and collaboration practices and opportunities for Latvians doing research and working across the world. Latvia’s attempts to support remigration and continuous academic and foreign policy interest in bringing the Latvian diaspora into the picture (Kļaviņš, Rostoks and Ozoliņa, 2014; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2018, 23, 2019, 25, 2020, 27-28, 2021, 25; Kļaviņš, 2021, 11), including from a comparative perspective (Birka and Kļaviņš, 2020), are noteworthy. However, this body of analysis represents a distinctively one-sided perspective on Latvia. A narrow focus on the country as awaiting solely individuals with certain types of affiliation to Latvia back to their motherland or encouragement for these individuals to maintain economically beneficial ties with Latvia neglects a much broader picture of Latvia as a country that is enriched by the talent arriving (and departing) from across the world.

More attention paid to the influx of students who have obtained their earlier academic degrees outside of Latvia and their future paths after completion of studies in Latvia widens the thematic scope of diplomatic studies revolving around Latvia. Additionally, it might bring new insights into studying human capital transformations and the impact of shorter migration experiences on mastering intercultural social skills. As the literature on the trans-local character of student life and student ambassadorship depicts, individual exposure to foreign contexts and interactions abroad entails an opportunity to master bridge-building across cultures and national or local contexts. International students are a vital group of internationally mobile human capital. Remarks that refer to the alumni being considered as Latvian ambassadors (Chankseliani and Wells, 2019, 12-13) show that public authorities in Latvia display some receptiveness towards the core thinking of educational diplomacy.

The limited inventory of Latvia’s educational diplomacy resources—scholarships and student experiences—remains understudied. It deserves more scholarly attention beyond this concise article. Riga, the capital of Latvia, hosts most (but not all) of the higher education institutions where international students are enrolled. Nevertheless, it should not be neglected that studying the intellectual ecosystem of each higher education institution or city might offer an even more nuanced picture of the student ‘ambassadorship’ features. Due to the overall limited pool of doctoral students at the Latvian higher education institutions and the tiny number of international students among them, it does not seem plausible to study science diplomacy in the Latvian setting. Thus, the conceptually blurred boundaries between educational and science diplomacies identified in the academic literature in one of the previous sections of the article do not resonate. This conceptual murkiness does not pose major issues for a study tailored to Latvia.

Conclusion

On the basis of the world’s leading examples and the academic and grey literature on these excelling higher education hubs, this article identified several educational diplomacy resources for Latvia. In accordance with the overall aim set out in the introduction, this article conveys several threads for further scholarly enquiry and policy considerations tied to Latvian diplomacy.

First, various exciting dynamics can deepen the general understanding of the multi-faceted student, academic, and research interactions across Asia and Europe beyond those tagged with the ASEM logo. In the Latvian context, the relatively understudied bottom-up dynamics and multi-faceted people-to-people-based connectivity stem from the growing international student presence and mobility. Those are talent flows that occur mainly outside the ASEM-tagged initiatives' framework but remain relevant for the overall thinking on the balanced mobility tied to the ASEM Education Process. More and more students from Asia choose Latvia (and, with it, Europe) as their study destination. It is not a trend restricted solely to the ASEM participating entities. To embrace these developments, this article puts forward an innovative research agenda to study in greater detail tertiary students enrolled in Latvia who have obtained prior education in Asia. It is an important topic for furthering knowledge of Asia-Europe relations in diplomacy studies and higher education. Likewise, it would contribute to the continuous research enquiry into how, where, and on what occasions Europe and Asia are brought together through increased daily encounters, study experiences, and people-to-people contacts.

Additionally, a closer analysis of these dynamics would provide a more comprehensive picture of Latvia as an active part of the overall European higher education landscape. A more nuanced study of the pool of international students and the pathways taken by receivers of Latvian scholarships would complement the existing (and rather one-sided) body of literature dedicated to the academic and professional tracks of young and highly mobile individuals of Latvian origin.

Then, educational diplomacy is a promising anchor for such future exploration. Though it should not be forgotten, educational diplomacy has evolved as a somewhat one-sided research pattern. It places students as the cherished agents of diplomatic potential at the centre stage to bring together nations and (along with them) their interests.

Consequently, scholarly thinking on educational diplomacy has shown little consideration of the managerial aspects and administrative burden that has already proven to be challenging in specific academic contexts in Europe. Thus, balancing out the enthusiasm for welcoming to the country young and ambitious knowledge seekers with corresponding implications on the new administrative, managerial, social, and economic considerations brought across the spectrum of institutions involved in the processing and servicing of such student flows would introduce a more balanced and comprehensive picture of the educational diplomacy.

While students form an essential part of an internationalisation strategy for higher education, research institutions, and countries, they are not the only component. Thus, a plethora of diverse dynamics could be studied in more detail to build the overall empirical picture of explicit and implicit educational diplomacy practices. Of course, the breadth and scope may vary from country to country. The world’s leading study and research destinations employ a remarkably vast range of educational, cultural, and public diplomacy resources. However, even small states with lean institutions and compact student pools, such as Latvia, offer diverse pathways for exploring educational diplomacy potential and practices with or without the broader contextual background of cultural and public diplomacies.

Next, the reviewed literature reveals an interesting nuance. While Latvia is benefiting from an influx of increasing numbers of international students, especially from Asia, including its notable points of gravity—India and Russia—the academic considerations at the Latvian higher education and research institutions and cross-country collaborations remain anchored within the eastern areas of the Baltic Sea Region. The geographical scope widens when individuals of Latvian origin who study abroad are brought into the overall picture (as part of the diaspora). It expands across the western shores of the Baltic Sea Region and even further. There is room for broadening the overall horizon. This article is one of such first attempts to explore other dimensions of how Latvia fits within the global shifts of higher education and research cores, peripheries, networks, and talent flows. Furthermore, this article highlights the intertwining effects of educational diplomacies and ambassadorships that come along with the rich competence and expertise background obtained by each internationally mobile student.

After, it is worth noting that recently the higher education nuances of Latvia have attracted interest not solely among researchers of Latvian origin or doing research at Latvian higher education institutions. Such an increasing pool of engaged researchers enriches the overall reflections with new considerations and diverse perspectives, including notions of ‘Latvian ambassadors’. Thus, it is an overall dynamic area of scholarly enquiry where more empirical insights from Latvia would help bridge some geographic coverage gaps.

Finally, following the latest thinking of the ASEM Education Process, it is worth considering for future educational diplomacy studies to touch upon the balanced mobility considerations that guide students from Latvia to embark on or defer pursuing studies in Asia. This research angle would help to keep multiple vectors on the scholarly agenda. The study mobility should be continuously examined as a multi-directional process.

____________________________

1 One excellent empirical example for a future study of this intertwined complexity is the Quad Fellowship. This fellowship opens doors to the United States universities to bring together the brightest graduate minds from Australia, India, Japan and the United States who specialise in science and technology (The White House, 2021). The Quad Fellowship is positioned as a component of the people-to-people exchange and education. However, due to its focus on advanced researchers and distinct science fields, it could be an attractive empirical example for the studies of both educational and science diplomacies.

2 Statistics of the number of foreign students were composed of all individuals who do not hold a passport or another type of identity document issued by Latvia. Those are both students who are enrolled in full time studies at a higher education institution in Latvia, as well as students who pursue exchange studies in Latvia. The table captures a selection of years taken from the annual report of the Ministry (Ministry of Education and Science, 2021b, 19).

3 Statistics obtained from the open-access data base of the National Statistical System of Latvia (2022) maintained by the National Statistics Bureau of Latvia. The statistics state students by country, where previous education was attained, not their country of citizenship.

The position of Russia within the ASEM context has shifted from the “Third/Pacific Group” comprising Australia, New Zealand, and Russia (Korhonen, 2013, 39) to being considered as part of Asia (Blanchemaison, 2016, 133; Degueldre and Reynders, 2021, 94).

The abbreviation “ENP” placed next to Ukraine stands for the European Neighbourhood Policy – a framework for addressing countries from both Eastern and Southern European neighbourhoods.

References

Aksakal, M., & Schmidt, K. (2019). The Role of Cultural Capital in Life Transitions Among Young Intra-EU Movers in Germany. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(8), 1848–1865. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1679416

Amaresh, P. (2020, December 3). India’s Educational and Cultural Cooperation with SAARC Countries. The Diplomatist. https://diplomatist.com/2020/12/03/indias-educational-and-cultural-cooperation-with-saarc-countries/

Angress, A., & Wuttig, S. (eds) (2018). Looking Back and Looking Ahead: The ASEM Education Process – History and Vision 2008 - 2018. Bonn-Berlin: Lemmens Medien GmbH. https://www.lemmens.de/medien/buecher-ebooks/wissenschaft-hochschule-forschung/asem

Apsite-Berina, E., Robate, L.D., Krisjane, Z., & Burgmanis, G. (2020). The Geography of International Students in Latvia’s Higher Education: Prerogative or “Second Chance”, in Society. Integration. Education. Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference. Rezekne Academy of Technologies, 511–520. https://doi.org/10.17770/sie2020vol6.5043

Arceneaux, P. (2021). Information Intervention: A Taxonomy & Typology for Government Communication. Journal of Public Diplomacy, 1(1), 5–35. http://kapdnet.org/filedata/md_board/20210628134503_UrJ1yf7k_02._Information_Intervention2C_A_Taxonomy_26_Typology_for_Government_Communication.pdf

ASEM. (2021). ASEM Education 2030 Strategy Paper. https://asem-education.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/ASEM-Education-Strategy-Paper-Final-Version.pdf

ASEM Education Secretariat (2019). ASEM Education Stocktaking Report: From Seoul to Bucharest. https://asem-education.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Executive-Summary_AEP-Stocktaking-Report-From-Seoul-to-Bucharest.pdf

ASEMME8. (2021). 8th ASEM Education Ministers' Meeting (ASEMME8) 15 December 2021 Online, Hosted by Thailand "ASEM Education 2030: Towards more resilient, prosperous, and sustainable futures". Conclusions by the Chair. https://asem-education.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Conclusions-by-the-Chair_ASEMME8_Final_Version.pdf

Auers, D., & Gubins, S. (2016). Augstākās izglītības eksporta ekonomiskā nozīme un ietekme Latvijā. Rīga: Certus. http://certusdomnica.lv/agenda/augstakas-izglitibas-eksporta-ekonomiska-nozime-un-ietekme-latvija/

Auers, D., Rostoks, T., & Smith, K. (2007). Flipping Burgers or Flipping Pages? Student Employment and Academic Attainment in Post-Soviet Latvia. https://www.cerge-ei.cz/pdf/gdn/rrc/RRCV_46_paper_01.pdf

Ayhan, K. J., & Gouda, M. (2021). Determinants of Global Korea Scholarship Students’ Word-of-Mouth About Korea. Asia Pacific Education Review, 22, 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-020-09648-8

Badel, L. (2016). Regards français sur la genèse d’un dialogue interrégional, l’ASEM (Asia Europe Meeting). Relations internationales, 4(168), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.3917/ri.168.0059

Barrier, J., Quéré, O., & Vanneuville, R. (2019). The Making of Curriculum in Higher Education: Power, Knowledge, and Teaching Practices. Revue d’anthropologie des connaissances, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.3917/rac.042.0033

Becker, W., M. Domínguez-Torreiro, A. R. Neves, C. T. Moura, & Saisana, M. (2021). Exploring the link between Asia and Europe connectivity and sustainable development. Research in Globalization, 3(100045), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resglo.2021.100045

Berkman, P.A. (2023). Science Diplomacy with Diplomatic Relations to Facilitate Common-Interest Building. In P.W. Hare, J. L. Manfredi-Sánchez & K. Weisbrode (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Diplomatic Reform and Innovation (pp. 673–689). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-10971-3

Bērziņa, K. (2015). Latvia: EU Presidency at a Time of Geopolitical Crisis. In A Region Disunited? Central European Responses to the Russia-Ukraine Crisis (pp. 25–28). German Marshall Fund of the United States. http://www.jstor.com/stable/resrep19010.9

Biagi, F., Castaño Muñoz, J., & Di Pietro, G. (2020). Mismatch Between Demand and Supply Among Higher Education Graduates in the EU. JRC Technical Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/003134

Billion, D., & Insel, A. (2013). Universités francophones: Un nouvel instrument d’influence? L’exemple de Galatasaray. Revue internationale et stratégique, 1(89), 117–122. https://doi.org/10.3917/ris.089.0117

Birka, I., & Kļaviņš, D. (2020). Diaspora Diplomacy: Nordic and Baltic Perspective. Diaspora Studies, 13(2), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/09739572.2019.1693861

Birziņa, R. (2012). E-Learning for Lifelong Learning in Latvia, 3–140. http://dspace.lu.lv/dspace/handle/7/1372

Bislev, A. (2017). Student-to-Student Diplomacy: Chinese International Students as a Soft-Power Tool. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 46(2), 81–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/186810261704600204

Blanchemaison, C. (2016). Vingt ans de dialogue entre l’Asie et l’Europe. Relations internationales, 4(168), 131–134. https://doi.org/10.3917/ri.168.0131

Bobotsi, C. (2021). EU Education Diplomacy: Embeddedness of Erasmus+ in the EU’s Neighbourhood and Enlargement Policies. EU Diplomacy Paper 3/2021. Bruges: College of Europe. https://www.coleurope.eu/fr/research-paper/eu-education-diplomacy-embeddedness-erasmus-eus-neighbourhood-and-enlargement-0

Bouchet-Sala, A. (2004). Le programme d’enseignement général à l’université de Stanford de 1935 à 1998 : transmission de substances de référence ou construction de métasubstances? Revue LISA/LISA e-journal, 2(1), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.4000/lisa.3093

Brazys, S., & Dukalskis, A. (2019). Rising Powers and Grassroots Image Management: Confucius Institutes and China in the Media. Chinese Journal of International Politics, 12(4), 557–584. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/poz012

Byrne, C., & Hall, R. (2013). Realising Australia’s international education as public diplomacy. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 67(4), 419–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2013.806019

Cabinet of Ministers (2021). Par Izglītības attīstības pamatnostādnēm 2021.-2027. gadam. Riga: Cabinet of Ministers. https://likumi.lv/ta/id/324332-par-izglitibas-attistibas-pamatnostadnem-2021-2027-gadam

Campbell, A.C., Lavallee, C.A., & Kelly-Weber, E. (2021). International Journal of Educational Development International Scholarships and Home Country Civil Service: Comparing Perspectives of Government Employment for Social Change in Ghana and Nigeria. International Journal of Educational Development, 82(102352), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102352

Camroux, D. (2006). The Rise and Decline of the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM): Asymmetric Bilateralism and the Limitations of Interregionalism, Les Cahiers européens de Sciences Po 6. Paris: Centre d'études européennes (CEE), Sciences Po. http://ideas.repec.org/p/erp/scpoxx/p0037.html

Capannelli, G., Lee, J.-W., & Petri, P. (2009). Developing Indicators For Regional Economic Integration and Cooperation. UNU-CRIS Working Paper W-2009/22. Bruges: UNU-CRIS. http://cris.unu.edu/developing-indicators-regional-economic-integration-and-cooperation

Carta, C., & Badillo, Á. (2021). National Ways to Cultural Diplomacy in Europe: The Case of Institutional Comparison. In C. Carta & R. Higgott (Eds.), Cultural Diplomacy in Europe: Between the Domestic and the International (pp. 63–88). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-21544-6_4

Carta, C., & Higgott, R. (2021). Conclusion: On the Strategic Deployment of Culture in Europe and Beyond. In C. Carta & R. Higgott (Eds.), Cultural Diplomacy in Europe: Between the Domestic and the International (pp. 239–261). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-21544-6_11

Carter, D. (2015). Living With Instrumentalism: The Academic Commitment to Cultural Diplomacy. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 21(4), 478–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2015.1042470

Chaban, N., & Elgström, O. (2020). A Perceptual Approach to EU Public Diplomacy: Investigating Collaborative Diplomacy in EU-Ukraine Relations. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 15(4), 488–516. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-BJA10029

Chamlian, L. (2019). European Union Studies as power/knowledge dispositif: Towards a reflexive turn. Culture, Practice & Europeanization, 4(2), 59–77. https://www.uni-flensburg.de/fileadmin/content/seminare/soziologie/dokumente/culture-practice-and-europeanization/cpe-vol.4-no.2-2019/chamlian-cpe-2019-vol.4-nr.2.pdf

Chankseliani, M., & Wells, A. (2019). Big Business in a Small State: Rationales of Higher Education Internationalisation in Latvia. European Educational Research Journal, 18(6), 639–655. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904119830507

Chong, A. (2022). Singapore and Public Diplomacy. In Chia, S.-A. (Ed.), Winning Hearts and Minds: Public Diplomacy in ASEAN (pp. 10–21). Singapore: Singapore International Foundation. https://doi.org/10.1142/12671

Commission of the European Communities (2001). Communication from the Commission. Europe and Asia: A Strategic Framework for Enhanced Partnerships. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=celex:52001DC0469

Cull, N. J. (2022). From soft power to reputational security: rethinking public diplomacy and cultural diplomacy for a dangerous age. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 18, 18–21. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-021-00236-0

Custer, S., Prakash, M., Solis, J.A., Knight, R., & Lin, J.J. (2019). Influencing the Narrative: How the Chinese government mobilizes students and media to burnish its image. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary. https://www.aiddata.org/publications/influencing-the-narrative

Darvas, Z. (2020). Resisting Deglobalisation: The Case of Europe. Working Paper Issue 1. Brussels: Bruegel. https://www.bruegel.org/2020/02/resisting-deglobalisation-the-case-of-europe/

Davies, S.R. (2021). Performing Science in Public: Science Communication and Scientific Identity. In K. Kastenhofer & S. Molyneux-Hodgson (Eds.), Community and Identity in Contemporary Technosciences (pp. 207–223). Sociology of the Sciences Yearbook vol. 31. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-61728-8_10

Degtjarjova, I., Lapina, I., & Freidenfelds, D. (2018). Student as Stakeholder: “Voice of Customer” in Higher Education Quality Development. Marketing and Management of Innovations, 2, 388–398. https://doi.org/10.21272/mmi.2018.2-30

Degueldre, E., & Reynders, N. (2021). Stocktaking Report 2021 ‘From Bucharest to Bangkok’. https://asem-education.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/ASEM-Education-Stocktaking-Report.pdf

Delcorde, R. (2021). La diplomatie d’influence. Revue Défense Nationale, 8(823), 57–63. https://doi.org/10.3917/rdna.823.0057

Drezner, D. W. (2020). The Song Remains the Same: International Relations after COVID-19. International Organization, 74(S1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000351

Emilsson, H., & Mozetič, K. (2019). Intra-EU Youth Mobility, Human Capital and Career Outcomes: The Case of Young High-Skilled Latvians and Romanians in Sweden. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(8), 1811–1828. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1679413

Eom, Y.H., Kim, D., Roh, S.M., & Lee, C.K. (2019). National reputation as an intangible asset: a case study of the King Sejong Institute in Korea. International Review of Public Administration, 24(2), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/12294659.2019.1611001

Ertem-Eray, T., & Ki, E.-J. (2022). Foreign-Born Public Relations Faculty Members’ Relationship with their Universities as a Soft Power Resource in U.S. Public Diplomacy. Journal of Public Diplomacy, 2(1), 6–27. https://www.journalofpd.com/_files/ugd/75feb6_448522e7d3534e39b5ab7a55668bf0e5.pdf

Fanoulis, E., & Revelas, K. (2023). The conceptual dimensions of EU public diplomacy. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 31(1), 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2022.2043836

Fominykh, A. (2020). Russian Public Diplomacy Through Higher Education. In A.A. Velikaya and G. Sions (Eds.), Russia’s Public Diplomacy (pp. 119–132). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12874-6_7

Gaens, B. (Ed.) (2015). The Future of the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM): Looking Ahead Into the ASEM’s Third Decade. http://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/asem/docs/20150915-final-future-of-the-asem_website_en.pdf

Gaens, B., & Khandekar, G. (2018). Introduction. In B. Gaens & G. Khandekar (Eds.), Inter-Regional Relations and the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM). London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-59764-9_1

Gallarotti, G. M., & Sautedé, É. (2017). Le paradoxe pragmatique: les BRICS comme vecteur de la diplomatie d’influence. Hermès, 3(79), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.3917/herm.079.0183

Gast, A. P. (2021, January 22). A Foreign Policy for Universities: Science Diplomacy as Part of a Strategy, Science & Diplomacy, (January 2021: Special Issue), 1–4. https://www.sciencediplomacy.org/perspective/2021/foreign-policy-for-universities-science-diplomacy-part-strategy

Gazeau-Secret, A. (2013). «Soft power»: L’influence par la langue et la culture. Revue internationale et stratégique, 1(89), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.3917/ris.089.0103

Gharlegi, B. (2019). The Eurasia Integration Index: A concept note. Berlin: Dialogue of Civilizations Research Institute. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/94347/1/MPRA_paper_94347.pdf

Gienow-Hecht, J. (2019). Nation Branding: A Useful Category for International History. Diplomacy and Statecraft, 30(4), 755–779. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592296.2019.1671000

Gienow-Hecht, J.C.E., & Donfried, M.C. (2010). The Model of Cultural Diplomacy: Power, Distance, and the Promise of Civil Society. In J. C. E. Gienow-Hecht & M. C. Donfried (Eds.) Searching for a Cultural Diplomacy (pp. 13–29). New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qd42q

Guerlain, P. (2004). L’Université américaine dans le débat public après le 11 septembre. Revue LISA/LISA e-journal, 2(1), 154–167. https://doi.org/10.4000/lisa.3095

Guilhot, N. (2017). “The French Connection”: Elements for a history o international history in France. Revue française de science politique, 67(1), 43–67. https://doi.org/10.3917/rfsp.671.0043

Hare, P.W. (2023). Diplomacy the Neglected Global Issue: Why Diplomacy Needs to Catch Up with the World. In P.W. Hare, J.L. Manfredi-Sánchez & K. Weisbrode (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Diplomatic Reform and Innovation (pp. 3–20). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-10971-3_1

Hellendorff, B. (2016). Le dialogue Asie-Europe (ASEM) depuis les années 1990 : plus pertinent, moins intelligible. Relations internationales, 4(168), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.3917/ri.168.0077

Hemery, J. (2005). Training for Public Diplomacy: an Evolutionary Perspective. In J. Melissen (Ed.), The New Public Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations (pp. 196–209). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230554931

Higgott, R., & Proud, V. (2021). The Influence of Populism and Natonalism on European International Cultural Relations and Cultural Diplomacy. In C. Carta & R. Higgott (Eds.) Cultural Diplomacy in Europe: Between the Domestic and the International. Palgrave Macmillan, 141–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-21544-6

Hocking, B. (2005). Rethinking the “New Public Diplomacy”. In Melissen, J. (Ed.) The New Public Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations (pp. 28–43). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hong, M.S., Jeon, M., & Ayhan, K.J. (2021). International scholarship for social change? Re-contextualizing Global Korea Scholarship alumni’s perceptions of justice and diversity in South Korea. Politics and Policy, 49(6), 1359–1390. https://doi.org/10.1111/polp.12435

Huang, C., Jin, X., & Li, L. (2016). RIO Country Report 2015: China. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC102345

Huang, Z. A. (2021). The Confucius Institute and Relationship Management: Uncertainty Management of Chinese Public Diplomacy. In P. Surowiec & I. Manor (Eds.), Public Diplomacy and the Politics of Uncertainty (pp. 197–223). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54552-9

Huijgh, E. (2013). Changing Tunes for Public Diplomacy: Exploring the Domestic Dimension. Domestic Dimension. SURFACE, 62–73. https://surface.syr.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1018&context=exchange

Hwee, Y. L. (2006). The Ebb and Flow of ASEM Studies. In J. Stremmelaar and P. van der Velde (Eds.), What about Asia? Revisiting Asian Studies (pp. 69–86). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. Online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46n1pj.8

Istad, F., Varpahovskis, E., Miezan, E., & Ayhan, K.J. (2021). Global Korea Scholarship students: Intention to stay in the host country to work or study after graduation. Politics and Policy, 49(6), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/polp.12436

Johnson, J., Adams, J., Ilieva, J., Grant, J., Northend, J., Sreenan, N., Moxham-Hall, V., Greene K., & Mishra, S. (2021). The China question: Managing risks and maximising benefits from partnership in higher education and research. London: The Policy Institute, King's College London. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/policy-institute/research-analysis/the-china-question

Kahn, M., & Puri, A. (2017). La collaboration des BRICS dans les domaines de la science, de la technologie et de l’innovation. Hermès, 3(79), 124. https://doi.org/10.3917/herm.079.0124

Kaša, R. (2019). The Nexus Between Higher Education Funding and Return Migration Examined. In R. Kašaand & I. Mieriņa (Eds.), The Emigrant Communities of Latvia (pp. 283–298). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12092-4

Kauppi, N. (2019). Waiting for Godot? On Some of the Obstacles for Developing Counter-forces in Higher Education. Globalizations, 16(5), 745–750. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2019.1578100

Kilias, J. (2021). Not Only Scholarships: The Ford Foundation, Its Material Support, and the Rise of Social Research in Poland. Serendipities. Journal for the Sociology and History of the Social Sciences, 5(1–2), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.7146/serendipities.v5i1-2.126089

King, K. (2014). China’s Higher Education Engagement with Africa: A Different Partnership and Cooperation Model? International Development Policy | Revue internationale de politique de développement, 5. https://doi.org/10.4000/poldev.1788

King, R., Lulle, A., Parutis, V., & Saar, M. (2018). From Peripheral Region to Escalator Region in Europe: Young Baltic Graduates in London. European Urban and Regional Studies, 25(3), 284–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776417702690

King, R., Lulle, A., & Buzinska, L. (2016). Beyond Remittances: Knowledge Transfer among Highly Educated Latvian Youth Abroad. Sociology & Development, 2(2), 183–203. https://doi.org/10.1525/sod.2016.2.2.183

Kirch, A. (2018). “Knowledge Workers” in the Baltic Sea Region: Comparative Assessment of Innovative Performance of the Countries in the Macro-Region. Baltic Journal of European Studies, 8(1), 176–196. https://doi.org/10.1515/bjes-2018-0010

Kļaviņš, D. (2021). The Transformation of the Ministries of Foreign Affairs in the Baltic countries. Journal of Baltic Studies, 52(2), 245–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/01629778.2021.1912790

Kļaviņš, D., Rostoks, T., & Ozoliņa, Ž. (2014). Foreign Policy “On the Cheap”: Latvia’s Foreign Policy Experience from the Economic Crisis. Journal of Baltic Studies, 45(4), 435–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/01629778.2014.942675

Knight, J. (2023). Knowledge Diplomacy: A Conceptual Analysis. In P.W. Hare, J. L. Manfredi-Sánchez, & K. Weisbrode (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Diplomatic Reform and Innovation. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 59–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-10971-3

Kochhar, E. (2021). Exploring the Potential of India-EU Cooperation in Education: Erasmus+ and More. In N. Inamdar, P. Vijaykumar Poojary & P. Shetty (Eds.), Contours of India-EU Engagements: Multiplicity of Experiences (pp. 224–241). Manipal: Manipal Universal Press.

Krenn, M. L. (2017). The History of United States Cultural Diplomacy: 1770 to the Present Day. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Lapiņa, I., & Ščeulovs, D. (2014). Employability and Skills Anticipation: Competences and Market Demands. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 156(April), 404–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.11.211

Le Thu, H. (2014). Evaluating the Cultural Cooperation: The Role of the Asia-Europe Foundation (ASEF) in the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) Process. Asia Europe Journal, 12(4), 401–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-014-0390-x

Lechervy, C. (2016). L’ASEM : le début d’un (mini-)pivot européen vers l’Asie-Pacifique ? Relations internationales, 4(168), 117–130. https://doi.org/10.3917/ri.168.0117

Lee, E. D., Alvis, S., Bingham, B., Fowle, K., Jones, T.V., Kumar, A., Linak, M., Wells, B., Bess, C. (2021). Higher Education Institutions and Science Networks: Unique International Platforms for Accelerated Response to Global Shocks. Science & Diplomacy, (January 2021 Special Issue), 1–11. https://www.sciencediplomacy.org/article/2021/higher-education-institutions-and-science-networks-unique-international-platforms-for

Lei, W., & Sordia, C. (2017). Échanges interculturels et Ligue des universités des BRICS. Le point de vue de la diplomatie publique chinoise. Hermès, 3(79), 111–113. https://doi.org/10.3917/herm.079.0111

Lien, D., Tang, P., & Zuloaga, E. (2022). Effects of Hallyu and the King Sejong Institute on International Trade and Services in Korea. The International Trade Journal, 36(1), 6–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853908.2021.1990165

Lim, M.A., Anabo, I.F., Phan, A.N.Q., Elepaño, M.A., & G. Kuntamarat (2023). The State of Higher Education in Southeast Asia. EU-SHARE Report. https://www.share-asean.eu/publications

Lulle, A., & Bankovska, A. (2019). Fateful Well-Being: Childhood and Youth Transitions Among Latvian Women in Finland. Nordic Journal of Migration Research, 9(2), 221. https://doi.org/10.2478/njmr-2019-0012

Lulle, A., & Buzinska, L. (2017). Between a “Student Abroad” and “Being From Latvia”: Inequalities of Access, Prestige, and Foreign-Earned Cultural Capital. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43(8), 1362–1378. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1300336

Lyons, E. E., Lipsand, K., & Obonyo, E. (2021). Catalyzing U. S. Higher Education to Build a Be er post-Pandemic Future through Science Diplomacy. Science & Diplomacy, (January 2021: Special Issue), 1–8. https://www.sciencediplomacy.org/article/2021/catalyzing-us-higher-education-build-better-post-pandemic-future-through-science

Macdonald, S., & Vlaeminck, E. (2021). A Vision of Europe Through Culture: A Critical Assessment of Cultural Policy in the EU’s External Relations. In C. Carta and R. Higgott (Eds.), Cultural Diplomacy in Europe: Between the Domestic and the International (pp. 41–62). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-21544-6

Mäkinen, S. (2016). In Search of the Status of an Educational Great Power? Analysis of Russia’s Educational Diplomacy Discourse. Problems of Post-Communism, 63(3), 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2016.1172489

Martel, F. (2013). Vers un «soft power» à la française. Revue internationale et stratégique, 1(89), 67–76. https://doi.org/10.3917/ris.089.0067

Mazais, J., Lapiņa, I., & Liepiņa, R. (2012). Process Management for Quality Assurance : Case of Universities. In 8th European Conference on Management, Leadership and Governance. Pafos: Neapolis University Pafos, 522–530.

McConachie, B. (2019). Australia’s use of international education as public diplomacy in China: foreign policy or domestic agenda? Australian Journal of International Affairs. Taylor & Francis, 73(2), 198–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2019.1568388

McGill Peterson, P. (2014). Diplomacy and Education: A Changing Global Landscape. International Higher Education, 75, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2014.75.5410

Melnikova, J., & Zaščerinska, J. (2016). Integration of Entrepreneurship into Higher Education (Educational Sciences) in Lithuania and Latvia: Focus on Students’ Entrepreneurial Competences. Regional Formation and Development Studies, 18(1), 100–109. https://sciendo.com/pdf/10.1515/cplbu-2017-0022

Ministry of Education and Science (2021). Pārskats par Latvijas augstāko izglītību 2020.gadā. Galvenie statistikas dati. Riga. https://www.izm.gov.lv/lv/media/12842/download

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2021). Ārlietu ministra ikgadējais ziņojums par paveikto un iecerēto darbību valsts ārpolitikā un Eiropas Savienības jautājumos 2021. gads. Riga. https://www.mfa.gov.lv/lv/jaunums/arlietu-ministra-ikgadejais-zinojums-par-paveikto-un-iecereto-darbibu-valsts-arpolitika-un-eiropas-savienibas-jautajumos-2021-gada?utm_source=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2018). Ārlietu ministra ikgadējais ziņojums par paveikto un iecerēto darbību valsts ārpolitikā un Eiropas Savienības jautājumos 2018. gads. Riga. https://www.mfa.gov.lv/lv/jaunums/arlietu-ministra-ikgadejais-zinojums-par-paveikto-un-iecereto-darbibu-valsts-arpolitika-un-eiropas-savienibas-jautajumos-2018-gada

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2019). Ārlietu ministra ikgadējais ziņojums par paveikto un iecerēto darbību valsts ārpolitikā un Eiropas Savienības jautājumos 2019. gads. Riga. https://www.mfa.gov.lv/lv/jaunums/arlietu-ministra-ikgadejais-zinojums-par-paveikto-un-iecereto-darbibu-valsts-arpolitika-un-eiropas-savienibas-jautajumos-2019-gada

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2020). Ārlietu ministra ikgadējais ziņojums par paveikto un iecerēto darbību valsts ārpolitikā un Eiropas Savienības jautājumos 2020. gads. Riga. https://www.mfa.gov.lv/lv/jaunums/arlietu-ministra-ikgadejais-zinojums-par-paveikto-un-iecereto-darbibu-valsts-arpolitika-un-eiropas-savienibas-jautajumos-2020-gada

Ministry of Science and Education (2019). Izglītības jomas eksperti diskutēs par Latvijas augstskolu iekļaušanos pasaules kartē. Riga. https://www.izm.gov.lv/lv/jaunums/izglitibas-jomas-eksperti-diskutes-par-latvijas-augstskolu-ieklausanos-pasaules-karte

Moon, R. J. and G.-W. Shin (2016). Aid as Transnational Social Captial: Korea’s Official Development Assistance in Higher Education. Pacific Affairs, 89(4), 817–837. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44874328

Müller, G., Raube, K., Sus, M., & Deo, A. (2021). Diversification of International Relations and the EU: Understanding the Challenges. ENGAGE Working Paper No. 1. https://www.engage-eu.eu/publications/diversification-of-international-relations-and-the-eu

Mulvey, B. (2021). Conceptualizing the Discourse of Student Mobility Between “Periphery” and “Semi-periphery”: The Case of Africa and China. Higher Education, 81, 437–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00549-8

Munusamy, M. M., & Hashim, A. (2021). An analysis of the ASEM Education Process and its role in higher education. European Journal of Education, 56, 468–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12462

Naddeo, R., & Matsunaga, L. (2022). Public Diplomacy and Social Capital: Bridging Theory and Activities. Journal of Public Diplomacy, 2(1), 116-135. https://koreascience.kr/article/JAKO202218853244164.pdf

Nair, R. (2013). Educational Services in SAARC: A Case For Deeper Integration. Nirma University Law Journal, 3(1), 19–49. http://docs.manupatra.in/newsline/articles/Upload/60C37EF8-CD27-4C4B-956B-A155D0AFC792.pdf

National Statistical System of Latvia (2022). Mobile students in Latvia by sex, country, where previous education was attained, education thematic group and educational attainment (at the beginning of school year) 2014 - 2021. https://data.stat.gov.lv/pxweb/en/OSP_PUB/START__IZG__IG__IGA/IGA050/

Nicholls, E. J., Henry, J.V., & Dennis, F. (2021). “Not in our Name”: Vexing Care in the Neoliberal University. Nordic Journal of Science and Technology Studies, 9(1), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.5324/njsts.v9i1.3549

Nikitina, T., & Lapina, I. (2017). Overview of Trends and Developments in Business Education. In WMSCI 2017 - 21st World Multi-Conference on Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics, Proceedings. Winter Garden, Florida: International Institute of Informatics and Systemics, 56–61. https://ortus.rtu.lv/science/en/publications/25614

Nye, J. (2017). Soft power: the origins and political progress of a concept. Palgrave Communications. Nature Publishing Group, 3(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2017.8