AEI-Insights: An International Journal of Asia-Europe Relations

ISSN: 2289-800X, Vol. 9, Issue 1, July 2023

DOI: https://doi.org/10.37353/aei-insights.vol9.issue1.5

Gareth Liu Zi Yuan

Department of Southeast Asian Studies, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

grtl907@gmail.com

Abstract

Although 2020 was supposed to be another “Visit Malaysia Year” and the Malaysian government had fully prepared for it; the Covid-19 pandemic put all the nation’s hopes on hold. The understanding of how the tourism industry in Malaysia can recover from a crisis is not yet complete, which has resulted in a lack of guidance for both industry professionals and researchers. The aim of this study is to determine the current state of Malaysia's tourism industry, evaluate the challenges faced by the industry, and provide recommendations to facilitate its recovery. Adopting a systematic review method, the study examined the difficulties faced by the Malaysian tourism industry, the challenges in different sectors, and the government policies recorded in 40 identified reports. A framework of recommendation that synthesises relevant research and targets to cushion the industry’s recession was established in order to enlighten future research in a Covid-19 or post-Covid-19 society on Malaysia’s tourism industry.

Keywords: Covid-19; Tourism Industry; Malaysia; 2020 Pandemic; Malaysia Tourism

Introduction

In the past 25 years, globalisation has become a buzzword (Bloom, 2020). More convenient moving and travelling, the rapidly developing internet, trade agreements, and fast-growing emerging economies all add up to globalisation’s explosion to an unprecedented height in recent decades and create a system in which people are connected to each other closer than ever. Due to this, the rapid global spread of Covid-19 has acutely impacted the global economy. People from all walks of life have been considerably affected, and the tourism industry is one of the worst hits by Covid-19. Most regions have been severely affected, which triggered a series of uncertainty, restrictions, and announcements made to undermine the tourism industry further which suggested that tourism-reliant destinations may not rebound from this pandemic (Wood, 2020). As a country that has been a popular tourist destination in the world for decades, during the pandemic, Malaysia has unfortunately experienced significant challenges.

Since the late 1990s, the tourism industry in the Southeast Asian region has been subjected to several crises accompanied by substantial falls in inbound tourism (Zahed, Ahmad & Henderson, 2012). Tourism in Malaysia emerged as vulnerable to regional and global events which act as a trigger for tourism crises, demanding a response in which various strategies are employed (Zahed, Ahmad & Henderson, 2012). Also, it is clearly difficult to anticipate and manage many tourism crises, considering the complex and multi-faceted nature of the industry (Faulkner, 2001; Prideaux, Laws, & Faulkner, 2003). Consequently, the tourism industry in Malaysia also faced multiple challenges and difficulties amid the pandemic.

The Covid-19 pandemic has been one of the most severe crises to hit the tourism industry globally, including in Malaysia. Malaysia, as a popular tourist destination, has been drastically impacted by the pandemic, with a significant drop in tourist arrivals and revenue. Malaysia's international borders were closed to most tourists in March 2020, resulting in a sharp decline in visitor arrivals and causing a ripple effect throughout the tourism industry, from hotels and restaurants to tour operators and transport providers. The pandemic's impact on Malaysia's tourism industry has been compounded by the government's strict measures to contain the spread of the virus, including lockdowns and movement restrictions. While these measures have been necessary to curb the spread of the virus, they have also had a severe economic impact, including on the tourism industry, which relies heavily on international visitors.

The implementation of the Movement Control Order (MCO) directly affected the local tourism industry’s deployment. The most affected one is the long-term prepared “Visit Malaysia Year (VMY) 2020. However, due to the raging Covid-19, the Ministry of Tourism Malaysia could only decide to cancel VMY 2020 in pity. The tourism industry is the second largest foreign currency income generator for the local economy. As the Ministry of Tourism’s original estimation, with the success of VMY 2020, the tourism industry could have brought the Malaysian government an expected income of RM100 billion. Yet, that hope is long gone. Covid-19 had forced the government to freeze the industry. For instance, out of countless tourist attractions, Genting Highlands is one of the most representative spots in Malaysia. In complying with the MCO, a total closure of the mountain’s casino, shopping malls, and entertainment venues was enforced. This is historically the first time that Genting Highlands has been closed for more than half a month since its grand opening five decades ago. Also, the multi-billion-ringgit outdoor theme park in Genting Highlands that was scheduled for a soft opening in the third quarter of 2020 has been postponed again. It was then estimated to open in the first half of 2022. To a great extent, this could illustrate how Covid-19 has cracked down on Malaysia’s tourism industry. Throughout the MCO period, most of the tourist attractions in Malaysia remained closed like Genting Highlands.

Following the closure of tourist attractions, a series of tourism-related events were also acutely affected by indefinitely postponed or directly cancelled. For example, the “George Town Festival”, scheduled to be held in July 2020 and 2021, is Malaysia’s annual international cultural event in Penang. The "George Town Festival" and the anniversary celebration of George Town's inclusion in the World Cultural Heritage were expected to attract a significant number of tourists and promote the local tourism industry's development as every year they invited artists from worldwide to perform. Inaugurated in 2010, GTW has been successful in positioning Penang as a cultural and arts hub, drawing attention to its rich heritage, unique attractions, and vibrant arts scene. These events typically draw in thousands of audiences and tourists from around the globe, which in turn generates revenue for the local economy and creates job opportunities. By cancelling these events due to Covid-19, the Malaysian tourism industry missed on an opportunity to showcase its cultural heritage, attract tourists, and boost the local economy.

The International Conference on Bajau/Sama and Maritime Affairs (ICONBAJAU 2020) and the Regatta Lepa and International Igal Festival 2020 were expected to contribute significantly to the promotion of sustainable tourism and the preservation of local knowledge. The conference, organized by the Sabah Native Affairs Council in collaboration with the Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture Malaysia (MOTAC), Universiti Malaya, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, and Sabah Museum, aimed to strengthen sustainable development goals through the exchange of knowledge and expertise. The conference would have addressed critical issues related to tourism, among other topics, and facilitated the exchange of ideas, knowledge, and practices. Similarly, the Regatta Lepa and International Igal Festival 2020, which is an annual event that celebrates the cultural heritage of the Bajau people, would have attracted thousands of tourists, and provided opportunities for the promotion of the state's tourism industry. The cancellation of these events due to the pandemic has resulted in short-term losses for the tourism industry and future strategy deployment of the state. It has also hindered the promotion of sustainable tourism practices and the preservation of the Bajau/Sama culture and heritage.

In conclusion, the Covid-19 pandemic has had a severe impact on Malaysia's tourism industry, which has faced numerous crises in the past. The complexity and multi-faceted nature of the industry make it challenging to anticipate and manage crises effectively. As a result, Malaysia's tourism industry is still struggling to recover from the pandemic's impact, highlighting the need for effective crisis management strategies and long-term planning to make the industry more resilient in the face of future crises. In order to have better preparation, two major research gaps must be identified and filled. Foremost, limited research is done on the long-term impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on the tourism industry in Malaysia, such as changes in consumer behaviour and preferences, and the sustainability of the industry in the post-pandemic period. Simultaneously, there is a lack of comprehensive studies on the effectiveness of the government's policies and strategies to support the tourism industry during the pandemic, including the allocation of funds and resources, and the implementation of various initiatives.

This study could have significant practical and policy implications for the government, tourism industry stakeholders, and the general public. Firstly, the study could provide insights into the current state of the tourism industry in Malaysia during the pandemic, including the impact of Covid-19 on tourism demand, supply, and employment. This information could be used by policymakers to formulate effective measures to support the industry and mitigate the negative effects of the pandemic. Additionally, the study could identify the key challenges facing the tourism industry in Malaysia and propose strategies to overcome them. This could include recommendations on how to diversify tourism offerings, develop new marketing and promotion strategies, and improve infrastructure and services to enhance the overall tourism experience. Last but not least, the study could contribute to the academic literature on the impact of the pandemic on the tourism industry, particularly in the context of Malaysia. This could help to advance the understanding of how pandemics affect the tourism industry and provide insights into how to better prepare for future crises.

Literature review

Tourism is considered one of the key resources in the development of modern societies (Freitag & Buhlmann, 2009). It promotes economic development and improves societal well-being (Herreros & Criado, 2008). Tourism activity has grown tremendously all over the world throughout the past twenty years (Hamzah, 2004), and it has become multiple countries' pillar industry that contributes to economic development. Since 2000, international tourism has grown significantly. In 2019, international tourist arrivals reached a total of 1.5 billion in 2019, representing a 4% increase from the previous year (UNWTO, 2020). The growth of the tourism industry is crucial to economic growth and related fields such as transportation, leisure services, and hospitality (Telfer, 2002). The tourism industry's impact on other industries has both positive and negative effects. According to the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC), tourism accounts for 10% of the world's GDP and jobs (WTTC, 2021). The Covid-19 pandemic has significantly impacted the tourism industry, with up to 50 million global travel and tourism jobs at risk, and a 25% decline in travel in 2020 (WTTC, 2021). The Asia-Pacific region is expected to be the most affected, with WTTC analysis and statistics projecting that approximately 30 million of the 50 million jobs at risk could be in Asia (Faus, 2020).

The main ‘essence’ of tourism experience remains something similar, namely feeling happier, better rest, closer to the family, less stress, and more relaxed (Euromonitor 2015). As an upper middle-income country, Malaysia's national tourism has entered the era of leisure-and-vacation-oriented tourism. The demand from tourists is more diversified compared to the past; also, the demand from the spiritual and cultural aspects is stronger than before. Cultural tourism products are drawing significant attention as interest in experiencing and learning about different cultures has grown widespread among tourists today. The assumption is that if tourism policymakers are not clearly defining their cultural values, along with appropriate strategies to restore their authenticity, it is likely that most of the cultural uniqueness will be underutilised and eventually lost (Debes, 2010). This principle can be used for Malaysia’s domestic inbound, outbound as well as international inbound tourism development.

Nevertheless, the tourism market is still mainly filled with sightseeing-oriented products. The little presence of culture-oriented products shows the imbalance of tourism product structure and the obvious mismatch between market supply and demand. At the same time, now in Malaysia, investment in the tourism industry prevails, the governments hope to earn more income out of the tourism industry by developing and promoting new scenic spots. However, there is a lack of creativity in both the development and promotion strategy of tourism projects. In a news article published by The Star in 2019, Malaysia's Tourism, Arts and Culture Minister at the time, Datuk Mohamaddin Ketapi, acknowledged the need for new and creative approaches in the tourism industry. The article also mentioned the importance of diversifying tourism products and services to cater to the changing demands of tourists. Apart from that, the homogenisation of scenic spots can be commonly seen, which finally leads to overheating or inefficient tourism investment. For instance, the mural painting which goes popular nationwide overnight. A system or management needs to be developed that takes every issue and challenge into consideration so that the decision-making process is reliable to optimise the value of assets in the Malaysia tourism industry (Ismail, Masron & Ahmad, 2014).

Tourism has been an important industry in Malaysia for a number of years (Khalifah & Tahir, 1997; Musa, 2000), and Malaysia has been one of the top two most popular tourist destinations in Southeast Asia and the Pacific regions (UNWTO, 2011). Before the pandemic, “Malaysia received around 26 million international tourists along with RM86.1 billion contributions to the revenue. The tourism industry has brought RM240.2 billion income to the country as one of the pillar industries, which consists of 15.9% of the national GDP” (Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture Malaysia, 2019). Even though there have been many scholars and studies drawing attention to crisis management in tourism; rather few of them have specialised in the aspect of the tourism industry’s countermeasures for the public health emergency, especially in the context of Malaysia. Goodall and Ashworth (2013) noted that the growth of the global tourism industry has prompted governments to recognize the economic and social benefits it can bring. However, the success of tourism depends on destination regions effectively marketing the destinations and managing crises.

According to Kadir, Ahmad, and Johari (2019), the intense competition in Southeast Asia requires Tourism Malaysia to develop effective strategies and attractive promotional packages to attract visitors. Four main challenges and pitfalls in the Malaysian tourism industry are the reduction of tourist arrivals, the need for skilled labour, the adoption of technology, and catering to the needs of Muslim travellers. However, one challenge that was not anticipated is the unexpected public emergency such as the Covid-19 pandemic, which has resulted in a significant decrease in tourist arrivals. Perimbanayagam (2020) revealed that tourist arrivals and spending were reduced by more than half in the first half of 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2020, the numbers dropped by 68.2 and 69.8 percent, respectively, from the same period the previous year, as claimed by Tourism, Arts, and Culture Minister Datuk Seri Nancy Shukri. Therefore, the concept of resilience has become vital in the tourism industry as pointed out by Chowdhury and Chhikara (2020).

However, the resilience of the local tourism sector alone is not enough to sustain. The Malaysian government and the public should also play a role in providing support. Hamid, Hashim, Shukur, and Marmaya (2020) stated that Malaysia is banking on its domestic tourism industry to provide momentum for tourism sector recovery and support. The government's measures to enhance resilience in the Malaysian tourism industry during the pandemic need to be further researched. Therefore, understanding the status of Malaysian tourism during the pandemic can help reinforce the industry's resilience in the future. The Covid-19 pandemic's response can catalyse the reinvention of the tourism industry's supply chain, and this study can serve as the basis for a more responsive and flexible operation. This study aims to fulfil the aspiration of summarizing the short-term elements of struggle while providing a foundation for a more resilient tourism industry in the future.

Methods

Methodology

The study focuses on the difficulties and challenges caused by Covid-19 for Malaysia’s tourism industry, based on the researcher’s six-month-long data collection and information accumulation from considerable channels of the sector. The researcher mindfully studied and referred to dozens of facts and findings from journal papers, publications, and authorised presses mostly between 2020 and 2021 in various aspects of the condition of the Malaysian tourism industry. A systematic review of these relevant literature was performed accordingly, which particularly assessed the Malaysian tourism industry during the Covid-19 crisis. The Systematic Literature Review (SLR) is a suitable method for this study because it synthesizes findings from recent journal papers, publications, authorised presses, and reports while narrowing the information gap, thereby offering suggestions and directions for further research. In this study, a three-step system for identifying literature was set up: screening and evaluating the relevant literature in order to answer the research questions. Consequently, the study is primarily made up of the SLR, and partially the secondary monographs which were creditably published by other researchers, as well as 10 detailed semi-structured interviews and discussions with the practitioners.

Search Strategy

The beginning of the three-step process starts with a thorough literature search. The researcher ranges literature published from 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2021. The starting date of 1 January 2001 was chosen because it marks the beginning of the 21st century and the era of globalisation, during which the tourism industry underwent significant changes and growth. This period saw the emergence of new technologies, increased international travel, and the development of new tourism markets, among other factors. The Covid-19 pandemic, which has had a profound impact on the tourism industry, began in 2019 and reached its peak in 2020. By including literature published from 2001 to 2021, the researcher is able to examine the tourism industry's trajectory over a 20-year period, including its response to previous crises and the impact of the pandemic. The year 2020 is the most significant as it is the year that the Covid-19 pandemic emerged.

The ISI Web of Science (WoS) was employed as the scientific search engine to look for matching literature. Despite the fact that WoS is considered the most widely utilised search engine for literature reviews; it does not include adequate tourism journals and updated news reports. The comprehensive internet search engine was therefore applied as the complementary database because its coverage is wider. The search profile was according to multiple primary search terms, the terms chosen were based on a literature review on the Malaysian tourism industry and crisis. In both WoS and online search engines, the “hospitality, tourism, leisure, and sports” category was used to modify and narrow down the hunt for suitable literature and information.

Inclusion Criteria

In terms of the main article selection, the inclusion criteria for this study were: 1) employment of the keywords designated for the title and abstracts of articles, 2) completed research, 3) research conducted concerning Malaysia, 4) English language literature, 5) use of quantitative and qualitative research methods. The exclusion criteria included: 1) abstracts only, 2) studies published in other languages that were unfamiliar to the researcher. Duplication was excluded too. Studies which fulfilled the inclusion criteria were listed and compared. When it came to the news and information selection, the inclusion criteria for this study were: 1) use of the keywords designated for the title and abstracts of articles, 2) confirmed sources, 3) solely associated with the subject of Malaysia, 4) English, Chinese or Malay language as a medium, 5) credible platform with evidence in publishing. The exclusion criteria included: 1) unverified information or unofficial sources, 2) reports released in other languages that were unfamiliar to the researcher, 3) repeated or redundant content of information. News reports that met the inclusion criteria were coded and authenticated.

Study Limitations

The study's limited time frame, which only covers the literature published from 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2021, and the exclusion of certain reference resources, including reviews, field surveys, observational studies, case studies, and news reports, are potential methodological limitations of the review. However, these exclusions were necessary to ensure the review's focus and reliability by prioritizing academic literature that met specific inclusion criteria, such as peer-reviewed articles and empirical studies. These sources were selected because they are more likely to provide rigorous and reliable information and analysis, which is essential for producing a credible review. While the exclusion of other reference resources may limit the review's scope, the approach adopted by the researcher enables a more in-depth and critical analysis of the academic literature relevant to the study's research questions.

Results

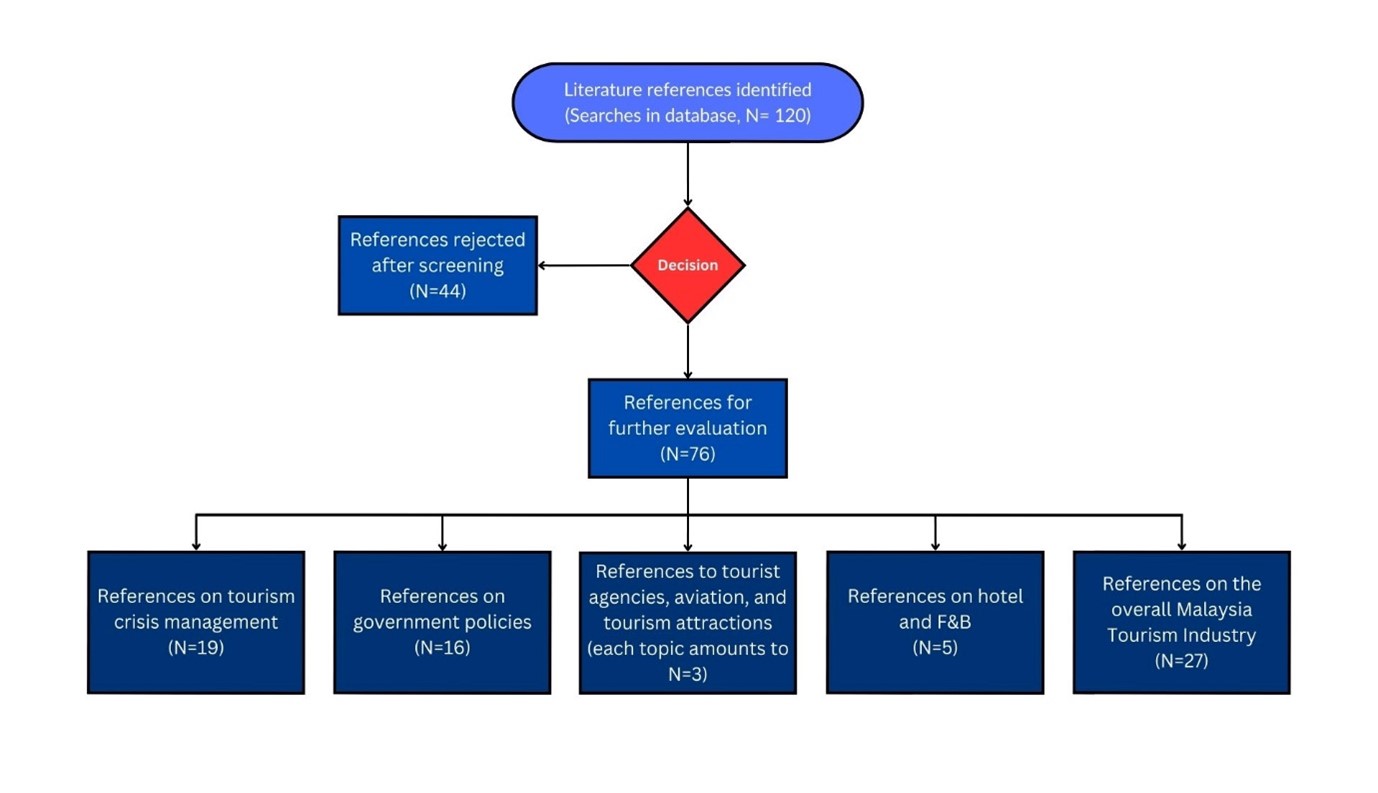

Figure 1 displayed the procedure followed for the purposes of this review and outlined the characteristics of the chosen references. Foremost, 120 studies/papers and other references such as books, conference proceedings, reports from the aforementioned databases were identified. Out of the 120, 44 were rejected after reading the shortlisted data as they were either duplicates or they had no proper abstract or were not composed in the researcher’s familiar language. Amongst the remaining 76 references, nearly half of them is Malaysia tourism-focused literature (n=36, 47%); original research articles (n=21, 28%); and non-research articles that consisted of reviews, case studies and news reports (n=19, 25%). Many of the literature references reported concrete evidence obtained on all sectors of the tourism industry including the overall industry (tourism) (n=27, 35%), hotel and F&B only (n=5, 7%), tourism agency only (n=3, 4%), aviation only (n=3, 4%), tourist attractions only (n=3, 4%), policy only (n=16, 21%), crisis management (n=19, 25%). 26 papers out of the literature references were written before 2011, nine out of the literature references were written from 2012 to 2019, and 50 out of the references were written after 2019, which indicates the severe impacts that the pandemic has brought to the tourism industry of Malaysia and the attention that the crisis management of tourism is drawing.

Difficulties and Challenges of Tourism during Covid-19

Tourism in Malaysia has been regularly and negatively affected by a series of crises that have struck the industry in the past two decades. The major ones include the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami and the 2003 SARS epidemic and the subsequent outbreaks of H1N1 (Zahed, Ahmad & Henderson, 2012). Since March 2020, Malaysia’s Covid-19 prevention and control have pushed tourism to a passive status. For the sake of guaranteeing the well-being of the nationals and effectively fighting against the pandemic, the government implemented a series of "Movement Control Order" (MCO). Under the devastating influence of Covid-19, carrying out MCO had put local tourism and its related industries in a position that is more difficult than ever. The attack of Covid-19 is a disastrous blow to all tourism industry practitioners in Malaysia, where the pressure and challenges that the industry has to face are unprecedented. The MCO, effective from March 16, which was supposed to last for two weeks only due to the unstable situation, was extended all the way to 2022. Throughout the MCO period, foreigners were prohibited from entering Malaysia (except for work purposes or the spouse of a Malaysian), and nationals without valid reasons were prohibited from going abroad, crossing states, and attending gatherings1. All sightseeing activities were cancelled or restricted, as everyone’s daily movement must follow standard operating procedure (SOP).

The tourism industry-related service line was also brutally decimated as part of the chain reaction. During the last decade, Malaysia consistently did well in attracting tourists from more countries and regions. Therefore, local hotels flourished. But in 2020 and 2021, due to the enforcement of MCO together with the entry ban, many hotels struggled to survive. Mr. Yap Lip Seng, the CEO of the Malaysian Hotel Association revealed that Malaysia will lose at least 60% of its tourism business by 2020. Within the industry, wages will be cut, and unpaid holidays will be practised as this is the only chance to save jobs. However, often, smaller hotels cannot afford this. Eventually, thousands of practitioners in the industry will find themselves ending up closing their business. To support the tourism businesses, the government and practitioners decide to use some hotels as mandatory quarantine centres to provide accommodation for Malaysians returning from overseas. Although the government promised RM150 per room per night and more than 23,000 rooms and 190 hotels appeared on the list; still, many of them were nevertheless not fully occupied. Senior Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob said the authority welcomes volunteers, and the volunteering hotels would be given Sales and Services Tax exemption for their involvement. Hotels willing to help could get in touch with the National Disaster Management Agency (Nadma) and the Tourism Ministry. The Malaysian Hotel Association, therefore, assumed that the emergency scheme would not lead to a significant upswing, but it still helped the participating hotels, considering that there was almost no income at all during this period. To a certain extent, this created a win-win situation for some hotels to weather the storm at that moment. According to the statistic given by the minister of tourism Datuk Seri Nancy Shukri, from March to October 2020, in total there were 109 hotels and guesthouses that shut down nationwide.

It was also a challenging period for the aviation industry. Air travel, being a dependent commodity, sees its demand affected by a variety of factors (Rhoades & Reynolds, 2007). Malaysia’s tourist travel was primarily relying on international and domestic flights. According to what the Malaysian Aviation Commission revealed, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, up to 1576 flights between January 1st and February 29th, this year were cancelled, which includes 376 Malaysia Airlines flights, 644 AirAsia flights, and 114 long-distance AirAsia X flights, and 442 Malindo flights. Starting from March 2020, with the imposition of MCO, the tourism industry in Malaysia experienced a significant decline. This led the Malaysian government to take steps to address the crisis by announcing the merger of the national airline, Malaysia Airlines, with the low-cost airline, AirAsia. The objective of this merger was to save both airlines and help them to navigate the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. However, the pandemic continued to impact the aviation industry, resulting in significant losses for Malaysia's two largest airlines. On the one hand, the domestic traffic by flights among states diminished; on the other hand, there were nearly no international flights. By the end of 2020, Malaysia Airport lost 75.5% of tourist arrivals compared to 2019. The whole aviation industry looked at a lag of 3 years at least before the businesses could bounce back to pre-Covid-19 days.

There was extremely low demand from the market as there were no more tourists. Thus, on account of the freezing of the industry, all the practitioners were soon getting unemployed. In Malaysia, there were over 3.6 million nationals in the tourism industry, which counts for 23.6% of the entire workforce. Referring to the Kenanga Investment’s research results, with the interference of MCO and supply chain, Malaysia’s unemployment rate soared to its highest level in 10 years in March 2020. The unemployment rate reached a high of 4 to 5%. Economists believed that the unemployment rate was expected to rise in the future, and tourism-related fields may be the hardest-hit industry. Following an analysis by the Affin Hwang Capital, employment in the tourism industry alongside its related fields affected by Covid-19 had potential downside risks and may drag on the overall employment performance. It was estimated that the annual unemployment rate of the tourism industry may rise to 5-6%, which was much higher than the 3.3% in 2019.

The recession is real. From March to December 2020, Malaysia's tourism industry entered the “off-season” period. The hibernation market and bleak financial condition have made all the practitioners now suffer and have started to look for self-help. According to the interview with the practitioner, the average loss for the small-size tourism agency was about RM15,000 per month. In terms of large travel agencies, most required employees to take unpaid leave. Some were laid off. Since February 2020, most of the bookings were cancelled. During the Recovery Movement Control Order (RMCO) period, the situation was slightly eased. As the third wave of pandemic started again in October 2020, the local tourism agencies had no business to run again. During such hardship, compared to the inbound group-oriented tourist agencies, those who ran more outbound groups were at a greater risk. According to the interview with the practitioners, during the pandemic the public was restricted to visit offshore destinations and the fear of visiting most countries, tourists would first request a withdrawal. However, usually, the airline and hotels will not allow the travel agency to withdraw the group tickets easily. The airline will follow its rules to detain the funds or postpone the bookings for three months, so the travel agency found difficulty in maintaining its cash flow. In order to keep surviving, many of the practitioners in the tourism industry took up part-time jobs or transferred to other industries. With the cancellation of tour groups, local tour guides faced the dilemma of unemployment. A large number of local tour guides received no job all year long. Before the implementation of MCO, the local tour guides launched some hidden spots in remote suburbs to try to save the stark local tourism industry. However, after the MCO, the tourism industry was completely suspended. Among all types of tour guides affected, those using Chinese as the medium of communication were the most affected. In the past several years, owing to the spike in numbers, the Chinese tour groups dominated the market. The demand for Chinese-speaking tour guides was the highest. Amid the pandemic, as Chinese tour groups have stopped coming to Malaysia, nearly all Chinese-speaking tour guide jobs have been paused.

Government efforts to overcome the difficulties and challenges

Concerning the great depression of the tourism industry in Malaysia, the federal government and the state government have both put forward plans to help the tourism industry and its practitioners. At the federal government level, the government has devised multiple measures to minimise the short-term impact of the pandemic, aimed primarily at the tourism industry. In the “Prihatin Rakyat Economic Stimulus Package”, the government guarantees the affected tourism industry’s practitioners income tax instalments which were suspended for six months. Before this stimulus package, the government allocated RM500 million to provide a 15% discount on electricity bills for the tourism sector. After MCO began, the Malaysian government demanded financial institutions to provide financial relief to borrowers by rescheduling or restructuring loans, and also offering payment moratoriums. There was a 100% stamp duty exemption arising from these rescheduling, restructuring, or moratoriums. The exemption was given until the end of 2020. The government can assist the cash flow of small and medium-sized enterprises (SME), as it had prepared a RM200 million and a RM500 million micro-credit scheme for small businesses in the tourism industry, and Bank Negara Malaysia was going to provide RM2 billion-worth in loans for SMEs. Each SME will be eligible to receive up to RM1 million with a tenure of 5.5 years. Moreover, Travel agencies, hotels, airlines, as well as businesses in the tourism industry, were given a deferment of their monthly tax instalments for six months starting April 1, 2020. Hotels were also exempted from service tax from March 1, 2020, until August 31, 2020.

To support the restoration of the tourism industry, the federal government allocated USD113 million in the form of travel discount vouchers and sharpened tourism promotion. The government collaborated with airlines, resorts, and hotels to offer discount vouchers of RM100 per person starting in March 2020. RM30 million was funded to Tourism Malaysia to increase the promotion of Malaysian tourism in the Middle East, Europe, ASEAN, and South Asia. In addition, a special income tax relief worth RM1,000 was available to individuals for expenses on domestic tourism from March 1 to August 31, 2020. It was limited to entrance fees for tourist attractions and expenses on accommodations at premises registered with the Ministry of Tourism, Arts, and Culture. While the effect of the policies and strategies being employed still needs to be further examined, the tendency and determination shown through actual movements to bring back the normalcy of domestic tourism have already released a positive signal and formed a solid start for the tourism industry to heal the wound. In November 2020, Tourism, Arts, and Culture Minister Datuk Seri Nancy Shukri said the government was upbeat about assisting tourism industry players in the country who had been badly affected by the Covid-19 pandemic for the survival of the industry. This was proven through the RM200 million allocation for the Tourism Recovery Plan under the Budget 2021, as tabled by Finance Minister Zafrul Aziz, and it was not a supplementary budget as it was the Budget for tourism for 2021. Apart from that, there was also an allocation for handicrafts. If in 2020 the ministry received only RM57 million, it would receive RM91 million for 2021. Under the Tourism Recovery Plan, "the Ministry would be implementing several initiatives such as discounts for tourist destinations, family holiday packages, arts and culture promotion, accommodation vouchers and Meet in Malaysia campaign," said the minister.

By the end of 2020, the government was showing its determination to rebrand Malaysia as among the 'Top of The Mind Ecotourism Destinations of the World' despite the local tourism industry struggling to survive amid the daunting pandemic. The goal to bestow Malaysia amongst the top ecotourism destination in the world would be possible with the implementation of the National Tourism Policy 2020 – 2030 (Dasar Pelancongan Negara 2020 - 2030) which was announced and launched by the Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin. Following the 17 objectives listed in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDG), Muhyiddin Yassin the then Prime Minister, said the DPN 2020-2030 was Malaysia's dynamic and strategic plan to spur the tourism industry in the country. According to National Tourism Policy 2020-2030 (MOTAC, 2020), other than sharpening Malaysia's competitiveness, Muhyiddin also mentioned that DPN 2020 – 2030 would be serving as a blueprint for Malaysia to build an inclusive and sustainable tourism industry that is well-prepared and resilient against potential disasters in the future. According to the Prime Minister, "the policy will be implemented through six core strategies namely governance transformation, establishing inclusive tourism investment zones, intensifying tourism digitalization, enriching the experience and satisfaction among tourists, strengthening commitment towards building sustainable tourism as well as increasing human resources capacity within all tourism sub-sectors". The government is aiming at luring more domestic and international investors by reviving cooperation between the public and private sectors through the Special Tourism Investment Zones. Also, technology-centred tourism development will be greatly encouraged as “technology development will strengthen the industry's network apart from paving the way for new innovative sub-sectors within the tourism sector and subsequently create more business and employment opportunities”. The PM believes that to “ensure the tourism product developments remain sustainable, competitive and inclusive as indicated under the DPN 2020-2030 is the government’s shared responsibility; hence, all parties are urged to work closely with the Tourism, Arts and Culture Ministry to confirm that the objectives outlined under the DPN 2020-2030 could be achieved”.

At the state level, in Pahang, Chief Minister Datuk Seri Wan Ismail announced the state government had set aside RM63,900 for tour guides whose livelihoods have been affected by the pandemic. 426 individuals comprising Taman Negara nature tour guides, and Taman Negara tour boat operators will each receive RM100 cash along with essential items worth RM50. Despite the initiatives appearing to aid, the processes involved in their implementation have been riddled with complaints. Referring to the chairman of Pahang Tourist Guides’ Association, Mr. Chin Yeong Chyuan, of the 130 active and registered guides of the association, only 7 received the allowance. At the end of March 2020, the State Tourism Administration - Tourism Pahang announced the second day after the state’s initiative is out, it has already assisted the Ministry of Finance with information about the qualified tour guides in the state. Later, the tour guides submitted personal information online. Most of the applicants who were eligible for the allowance, even though they have completed the online form and attached the bank account number through the official website of the Ministry of Finance; did not receive anything for two months. However, the Ministry of Tourism and the Ministry of Finance were unable to respond directly to this situation. Consequently, the initiative did not get to help the tour guides in the State promptly.

In the case of Johor, according to the report of New Strait Times, in May 21, 2020, the state government announced several incentives to assist the tourism industry players, including the allowance of one-time assistance to qualified tour guides, and exemption from the license fees of travel agencies and hotels, so as to help them survive the challenge. Johor State Tourism Committee chairman Datuk Onn Hafiz explained that 936 qualified tour guides living in Johor would receive the RM1,000 allowance, involving a total amount of RM936,000. The state government also exempted the license fees of travel agencies and hotels in the state in 2020. It is estimated that 1,031 license holders would benefit, and the exempted license fees were expected to reach RM 894,211. At the same time, theme parks and family entertainment centres in the state were waived from the entertainment duty that year too, which was about RM3 million. In addition to the above-mentioned benefits, the Johor State Tourism Committee worked on developing both long-term and short-term strategies to revive the tourism industry in the state after the end of the Covid-19 pandemic. The state government expected the incentives would help the industry practitioners to overcome the difficulties and challenges, and also to improve the performance of the tourism and service industry of the state.

As for Perak, based on the report of Sin Chew Daily, on December 24, 2020, Nolee Ashilin, who is in charge of the state’s housing and tourism, unveiled that the state would allocate 1.2 million to boost the tourism sector, which contained a one-time allowance for the native tour guide (RM 700 per person) and travel agency (RM 2000 per company), 10,000 #TravelPerakLah vouchers, and the one-time RM10,000 subsidy for 12 native tourism organisations and non-government organisations. According to her, the allowance for the registered tour guides and tour agencies was given to appreciate the practitioners’ effort to develop the tourism industry in Perak and to rejuvenate the sector during this pandemic. A subsidy for NGOs and tourism organisations was given to promote new tour packages to attract tourists to visit Perak. The continuously distributed travel voucher covered sightseeing, accommodation, and package, to maintain and enhance the confidence of tourists towards tourism in Perak. The state government allocated 4.4 million to support local tourism through the improvement of existing tour packages and marketing, with the aim of maintaining a dynamic and satisfactory tourism market that would encourage repeat visitation and consumption.

Discussion

In line with UNWTO’s data, in the first 10 months of 2020, the number of international tourists’ arrival dropped by 72%, which is historically the lowest since 1990. The number of tourists travels internationally is 900 million less than in 2019, which roughly equals to a USD935 billion loss. Hence, the organisation called on countries to step up their response to the pandemic without panic. Countries should take appropriate measures according to their condition to cushion the negative impact on the tourism industry, while unnecessary panic and extreme policies will lead to worse consequences than the pandemic itself. Effective crisis management can enhance the resilience of tourism organisations and destinations in crisis situations, strengthen their defence mechanisms, limit potential damages, and allow them to bounce back to normalcy faster (Paraskevas, Altinay, McLean & Cooper, 2013).

The government must keep the information open and transparent so that the general public will know the latest situation in time. In this process, the mass media plays an important role. For example, back in 2004, after the deadly tsunami, the media exaggerated the extent and harmful outcomes of the crisis and neglected the post-crisis period, failing to help rebuild tourists’ confidence by circulating positive stories. This is a universal phenomenon and there were many instances where media coverage has exacerbated and perhaps prolonged a destination’s crisis (Beeton, 2006). The government needs to lead a more proactive role in regulating, assisting, and reviving the tourism sector to heal. The tourism industry has been systematically impacted by the negative effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. On the one hand, the most direct impact of the pandemic on the supply side is that tourism-related enterprises suffer heavy losses and were trapped in a survival crisis, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises. On the other hand, the present suspension has provided a buffer period for the authority and practitioners to reflect and try to solve the problems that popped up in the industry.

Based on the literature reviewed, the findings on the challenges and issues faced by the tourism industry in Malaysia amid the Covid-19 pandemic are mostly in line with previous research. The reduction of tourist arrivals, supply-demand mismatch, underemphasis on domestic tourism, and lack of resilience have been identified as major challenges in the Malaysian tourism industry in previous studies. In addition, the impact of unexpected public emergencies such as the Covid-19 pandemic on the tourism industry has also been discussed in previous research, but not so much in the case of Malaysia. This discussion, thus, highlights the importance of domestic tourism development and soft power enhancement in the Malaysian tourism industry. Previous research has also emphasised the importance of domestic tourism in sustaining the tourism industry during times of crisis, and the potential of soft power to attract visitors to a destination. These are consistent with prior literature on the challenges and potential solutions for the tourism industry in Malaysia. However, it is important to note that the tourism industry is constantly evolving, and new challenges may emerge in the future. Therefore, ongoing research and analysis are necessary to ensure the sustainability and growth of the industry, especially when the pandemic is still underway.

The supply-demand reform for tourism products and industrial structure

In this Covid-19 crisis, not only effective tourism supply is facing a survival crisis, but also the ineffective supply is more likely to be eliminated. According to the official website of Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, various types of high-quality tourism resources in Malaysia are listed, including natural attractions such as national parks, beaches, islands, and rainforests; cultural and heritage sites such as temples, mosques, museums, and historical buildings; and adventure and sports activities such as diving, trekking, and water sports. After the recovery of the tourism market, and to precisely meet the manifold modern tourism demand, those high-quality local tourism resources that have been put aside in the Covid-19 crisis should be revitalised and optimised through the creative packaging and cultural implantation, to further increase the supply-side structural reform of the tourism industry. Moreover, an effective reorganisation and integration of tourism assets in the post-Covid-19 era could possibly change the competitive pattern of the tourism industry. Demand-wise, under the Covid-19 pandemic, there are hardly any tourists travelling between countries. The whole world is facing the same dilemma. Thus, in order to warm up and let the industry recover, the industry also needs to adjust and upgrade on the demand side, where demands must be stimulated and guaranteed again. For the sake of boosting the local tourism industry, the authority and the nationals of Malaysia have to play the most significant roles.

With regards to the supply side, tourism enterprises, especially small and medium-sized enterprises, need to solve the survival problem. The government should take the initiative to mitigate the immediate impact of the Covid-19 crisis. Other than current financial measures, the government may utilise different tools to ease the practitioners’ burden. For example, rent subsidies can be provided for tourism sector-related offices, buildings, and event spaces. Also, reasonable extra allowance from the federal government can be offered to those with zero income to help fulfil their essential needs. In addition, although crises and disasters cannot be stopped, their impacts can be limited by both public and private sector managers (Ritchie, 2004). During the MCO period, practitioners should seize the suspension of tourism to conduct a comprehensive survey regarding the market rather than simply relying on promotion after Covid-19 to rebuild their businesses. It will be wise for the industry to reshape products and services according to market demand because when the pandemic is over, the pent-up tourism demand will possibly be released rapidly or even multiplied in a short time. At this stage, only when the online marketing and the plan for returning to work are made, can the tourism blowout in the post-Covid-19 era be welcomed. Last but not the least, Ritchie (2008) also notes that understanding and subsequent management of incidents can be vastly improved through the extension and application of crisis and disaster management theory and concepts from other disciplines, coupled with the development of specific tourism crisis management research and frameworks. The public health emergencies have alerted the tourism industry to establish a tourism emergency mechanism as soon as possible. It should range from the system, materials, personnel, funds, and all other aspects, to provide security and preparation for the local tourism industry to cope with any unexpected crisis.

In relation to the demand side, the government needs to prioritise the restoration of the domestic tourism market, which is the paramount strategy for the Malaysia tourism industry to recover. Hetherington (2004) remarks that political trust operates like a stimulus that influences citizens’ decisions to support or oppose government policies. He argues that support for an expansion of services is likely high if the public perceives the institutions that will deliver those services as trustworthy. Due to the consideration of public health and safety, the recovery of the inbound tourism market will be later than that of domestic tourism. Trust is important to understand the world, functioning of institutions, decision-making processes, and social, political, and community relations because it underlies human and social life (Stein & Harper, 2003). Therefore, when revitalising the inbound tourism market, the authorities and the industry should establish a “safe destination” image to show the international society and vigorously develop tourism insurance to rebuild the trust of inbound tourists to the country. Bramwell and Lane (2011) comment that because the government has a primary influence on governance and policymaking for sustainable tourism, the roles and activities of the states directly affect tourism and the sustainable development of the industry and destinations. Thus, the biggest challenge after Covid-19 for the government will be restoring the trust of domestic and foreign tourists. The "Clean and Safe Malaysia" campaign is one of how this is to be achieved. The aim is to award certification to hotels that meet the requirements of the relevant authorities. Also, airlines, hotels, transport companies, and other operators should consider collaborating to provide joint travel packages. This will reduce costs for businesses and visitors and make the country's tourist industry more competitive.

The prioritised domestic tourism restoration for nationals

In a social media post by the Malaysian Tourist Board back on 16 May 2020, they had encouraged nationals, under the hashtag “#TravelLater”, to explore their own country after the crisis to bolster the local economy. Datuk Musa Yusof, the then director-general of Tourism Malaysia, had projected that it could take months for the tourism industry to recover from the impacts of Covid-19 and emphasized that the industry would need all the help it could get to rebuild. Historically, the domestic tourism market is usually the first to recover in the post-crisis era. Indeed, the inbound market can typically only stabilize and revive once the domestic tourism market has recovered. Reflecting on these past strategies in 2023, it's evident that Malaysia's concerted efforts to curb the pandemic led to a substantial growth in the tourism industry as initially hoped. Public support for tourism development, as Nunkoo & Ramkissoon argued in 2011, remains a prerequisite for the sustainable growth of the industry. Any lack of such support can hinder the growth and future potential of a destination. Therefore, it's crucial for a destination's government to gain the community’s endorsement for tourism to ensure socially compatible development. During the peak of the pandemic, the sentiment "Must go jalan jalan" resonated with many nationals who had been strongly advised to stay at home for several months. This sentiment drove a quick recovery in industries related to open-air natural scenic spots, such as the National Park in Pahang, Langkawi Island in Kedah, and Mount Kinabalu in Sabah. In retrospect, the key focus for the government and the industry was how to transform outbound tourism into domestic tourism in order to restore the total domestic tourism to pre-pandemic levels.

According to an Oxford University researcher Per Block’s definition, “travel bubbles, do away with that waiting period for a select group of travellers from certain countries where the coronavirus has been contained. In a ‘travel bubble’, a set of countries agree to open their borders to each other but keep borders to all other countries closed. Hence, people can move freely within the bubble, but cannot enter from the outside”. Since the RMCO stage began, the government eyes to create and consolidate the “green travel bubble”. Compared to directly pushing the bubble to an international level, the federal government aspires to practise it among states to stimulate the domestic tourism market. Thus, the “green travel bubble” scheme was launched in November 2020 to resuscitate the local tourism industry. “Green travel bubble under the tourism recovery plan, has three main objectives - first is to restore the people’s confidence to travel again, second is to revive the domestic tourism industry, and finally to maximise the available resources. Vehicles travelling within the travel bubble cannot make any stop in or cross red zones without first obtaining permission from the police”, said the tourism minister Datuk Seri Nancy Shukri. To further revitalise and invigorate the tourism sector, the minister also revealed that MOTAC has prepared SOPs and is ready for the international green travel bubble. The bubble initiative originally envisioned allowing Singaporeans to first vacation in Langkawi, which had been declared a virus green zone. Once the pandemic was effectively controlled in Malaysia, the plan was to gradually expand this travel bubble to include Hong Kong, Macau, Australia, New Zealand, China, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Thailand. This progression was designed to slowly permit travel for business and medical tourism purposes, eventually culminating in leisure and sightseeing tours by April 2022. Given the current year, it's important to evaluate and acknowledge the outcomes and impact of these strategies.

The attractive soft power enhancement tool for quality foreign tourists

Nye (1990) came up with a definition for “soft power” as “the ability to get what you want through attraction rather than through coercion”. From the perspective of soft power enhancement, Ooi (2016) believes that “the tourists become a geopolitical object and subject”. Simply put, Malaysia’s tourism industry can be employed as a tool of soft power enhancement too. Based on the statistics generated by Mohamad, Abdullah, and Mokhlis (2012), “foreign tourists were willing to come back to Malaysia for various positive reasons that include low-cost travel and living packages, cultural heritage, and natural scenes”. Therefore, Malaysia could enhance its soft power and attract the inbound tourism market to return by optimising the tourism environment, enriching the tourism product system, improving the quality of tourism services, and introducing policies such as tax refunds for tourism shopping as the MOTAC minister mentioned earlier, “under the current circumstance, Malaysia tourism needs to fancy tourists’ quality rather than quantity”. Tourists who can produce high expenditure while travelling should be the targeted audience at this stage. Up to date “tourism activities will continue to be allowed under strict standard operating procedures, as the recovery of MCO is extended to March 31, 2022”, said Defence Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob. Upon completion of all the boosting policies and methods, the tourism sector in Malaysia is slowly recovering since the mid of 2022 as the situation has been stabilised with the help of the vaccine.

Conclusion and Recommendations:

The Covid-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on Malaysia's tourism industry, which was expected to experience significant growth in 2020. The industry has been faced with various challenges, including operational difficulties, forced shutdowns, bankruptcy crises, and survival pressures. To address these challenges and revive the industry, a comprehensive approach involving both the government and the private sector is needed.

From the supply side, the study found that domestic tourism development is crucial in sustaining the tourism industry during the Covid-19 pandemic. The government has taken steps to promote domestic tourism, including offering attractive packages and launching campaigns to encourage Malaysians to travel within the country. However, the study also highlights the need for more innovative and creative tourism products and experiences to attract local tourists. From the demand side, the study found that Malaysia's soft power, particularly its cultural and natural heritage, can be further leveraged to attract international tourists. However, challenges such as the lack of effective government coordination of the practitioners and the need for friendly policy integration to enhance the tourism experience remain significant obstacles. Overall, the study suggests that a comprehensive approach, involving both the government and the private sector, is needed to address the challenges faced by the tourism industry in Malaysia. This includes promoting domestic tourism, enhancing the country's soft power, developing innovative tourism products, and improving infrastructure and technology.

This research has synthesized and assessed the available literature on the difficulties and challenges facing Malaysia's tourism industry during the Covid-19 pandemic. The study suggests that Malaysia should focus on helping industry practitioners survive first and then begin planning for future deployments. By prioritizing the survival of the industry, the tourism industry can gradually return to normalcy and aim for in-depth and high-speed progress.

To address the challenges facing Malaysia's tourism industry, the following recommendations are proposed:

To sum up, while the Covid-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on Malaysia's tourism industry, it also presents an opportunity for the industry to adapt and innovate. By implementing the recommendations proposed in this study, Malaysia's tourism industry can revive and thrive once again.

Limitations and Future Research

Due to the ongoing nature of the issue being studied, data for this research was collected from various sources, including mass media and scientific journals that specifically focus on the impact of Covid-19 on tourism, particularly in Malaysia. Only the WoS database was used for data collection, and Scopus was not included. To enhance this study, empirical research methods such as quantitative analysis or qualitative case studies involving multiple supply chain partners in Malaysia can be employed in future research to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the pandemic's impact on the tourism supply chain.

References

Beeton, S. (2006). Community development through tourism. Collingwood: Land Links.

Bethke, L. (2020). The coronavirus crisis has hit tourism in Malaysia hard. DW News

Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (2011). Critical research on the governance of tourism and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4/5), 411–421.

Chowdhury, I., & Chhikara, D. (2020). Recovery strategy for tourism industry post-pandemic. Mukt Shabd Journal, 9(8).

Debes, T. (2010). Cultural tourism: a neglected dimension of tourism industry. Anatolia - An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 22, 234-251.

“Economic Stimulus Package takes effect from today”. The Oriental Daily. 2020.04.01

Euromonitor (2015): WTM Global Trends Report.

Faulkner, B. (2001). Towards a framework for tourism disaster management. Tourism Management, 22(2), 135–147.

Faus, J., (2020). This is how coronavirus could affect the travel and tourism industry. World Economic Forum.

“Five Things to Know About Travel Bubbles”. Smithsonian Magazine. 2020.05.28

Freitag, M., & Buhlmann, M. (2009). Crafting trust: The role of political institutions in a comparative perspective. Comparative Political Studies, 42, 1537–1566.

Goodall, B., & Ashworth, G. (2013). Marketing in the Tourism Industry (RLE Tourism): The Promotion of Destination Regions. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hamid, R., Hashim, N. H. M., Shukur, S. A. M., & Marmaya, N. H. (2021). The Impact of Covid-19 on Malaysia Tourism Industry Supply Chain. International Journal of Academic Research inBusiness and Social Sciences, 11(16), 27–41.

Hamzah, A. (2004). Policy and planning of the tourism industry in Malaysia. In Proceedings from the 6th. ADRF General Meeting, Bangkok, Thailand

Herreros, F., & Criado, H. (2008). The state and the development of social trust. International Political Science Review, 29, 53–71.

Hetherington, M. J. (2004). Why trust matters: Declining political trust and the demise of American liberalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ismail, N., Masron, T. & Ahmad, A. (2014). Cultural Heritage Tourism in Malaysia: Issues and Challenges. 4th International Conference on Tourism Research (4ICTR), 12, p.8.

Khalifah, Z., & Tahir, S. (1997). Malaysia: Tourism in perspective. In F. Go, & C. L. Jenkins (Eds.), Tourism and economic development in Asia and Australasia (pp. 176–196). London: Cassel.

Ministry of Tourism and Culture Malaysia. (2018). 25.9 million International Tourists Visited Malaysia in 2017.

Ministry of Tourism, Arts, and Culture (MOTAC). (2020). National Tourism Policy 2020-2030.

Mohamad, M., Abdullah, A. R., & Mokhlis, S. (2012). Tourists’ evaluations of destination image and future behavioral intention: The case of Malaysia. Journal of Management and Sustainability, 2, pp.181-189.

Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2011). Developing a community support model for tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 964–988.

Nye, Joseph. (1990). Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power, London: Basic Books.

Ooi, C. (2016). Soft power, tourism. In J. Jafari & H. Xiao (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Tourism (pp. 1-2). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Paraskevas, A., Altinay, L., McLean, J. & Cooper, C. (2013) Crisis knowledge in tourism: types, flows and governance. Annals of Tourism Research, 41, 130-152.

Prideaux, B., Laws, E., & Faulkner, B. (2003). Events in Indonesia: Exploring the limits to formal tourism trends forecasting methods in complex crisis situations. Tourism Management, 24, 475–487.

Rhoades, D. L., & Reynolds, R. (2007). The perfect storm: Turbulence and crisis in the global airline industry. Crisis Management in Tourism (pp. 252–266). Wallingford: CABI

Ritchie, B. (2004). Chaos, crises, and disasters: a strategic approach to crisis management in the tourism industry. Tourism Management, 25(6), 669-683.

Ritchie, B. (2008). Tourism disaster planning and management: From response and recovery to reduction and readiness. Current Issues in Tourism, 11(4), 315-348.

Siti Aishah Abdul Kadir, Azlinda Ahmad & Mohd Hasrul Yushairi Johari. (2019). Challenges and Pitfalls in the Operation of Malaysia Tourism and Hospitality Industry. Wood Technology, Engineering and Science Social.

Stein, S. M., & Harper, T. L. (2003). Power, trust, and planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 23, 125–139.

Telfer, D. (2002) the evolution of tourism and development theory. In R. Sharpley and D. Telfer (eds) Tourism and Development: Concepts and Issues (pp. 3578). Clevedon: Channel View.

Tse, S. (2006). Crisis management in tourism. In D. Buhalis, & C. Costa (Eds.), Tourism management dynamics: Trends, Management, and Tools (pp. 28–38). London: Butterworth-Heinemann.

UNCTAD. (2020). Impact of the coronavirus outbreak on global FDI. Investment Trends Monitor.

UNWTO (World Tourism Organization) (2020). UNWTO World Tourism Barometer 2019

Wood, L. (2020). Strategic actions that destinations can take: Coronavirus (Covid-19) - Case Study. Research and Markets.

WTO. (2020) WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on Covid-19. World Health Organization (WHO) Press.

Zahed, G., Ahmad, P. & Henderson, J. (2012). Tourism crises and island destinations: Experiences in Penang, Malaysia. Tourism Management Perspectives, 2(3), 79-84.

“AirAsia, Malaysia Airlines merger an option as Covid-19 hits industry: Minister Azmin”. (2020, April 17). The Strait Times.

“Aviation Industry is under darkness still due to the low demand”. (2021, January 15). Sinchew Daily.

“Covid-19: Genting Resort’s theme park, casino, hotels shut down for two weeks, refunds available”. (2020, March 17). The Malay Mail.

“Covid-19: Tourism Ministry cancels Visit M'sia Year 2020”. (2020, March 18). The Star.

“Economic Stimulus Package takes effect from today”. (2020, April 1). The Oriental Daily.

“Five Things to Know About Travel Bubbles”. (2020, May 28). Smithsonian Magazine.

“Genting’s theme park opening delayed by a year”. (2020, May 27). The Star.

“Hit by the Covid-19, tour guides change job to self-rescue”. (2020, April 7). Sinchew Daily.

“International Tourism Faces Biggest Slump since 1950s: UNWTO”. (2020, May 28). The New York Times.

“Johor govt announces incentives for tourism sector”. (2020, May 21). New Strait Times.

“Kenanga Investment Bank: CMCO to boost domestic spending”. (2020, May 4). The Malay Mail.

“Mahathir announces RM20 billion economic stimulus package to mitigate Covid-19 impact in Malaysia”. (2020, February 27). CNA.

“Malaysia and China set 2020 as Year of Culture and Tourism”. (2018, August 21). The Star.

“Malaysia’s biggest Covid-19 cluster linked to Sri Petaling tabligh event ends today after four months”. (2020, July 8). The Malay Mail.

“Malaysia: First cases of 2019-nCoV confirmed January 25”. (2020, January 25). GardaWorld.

“Malaysia is ready for international travel bubble, said Nancy”. (2020, November 26). Sinchew Daily.

“Malaysia launches ‘green travel bubble’ scheme”. (2020, November 25). HRMASIA.

“Malaysia to achieve target of 33.1 million tourist arrivals in 2018”. (2018, August 25). New Strait Times.

“Malaysia’s tourism industry decimated by the shutdown”. (2020, March 24). Free Malaysia Today.

“Malaysia’s unemployment rate highest in 12 years”. (2020, May 13). Vietnam Plus.

“MCO crashes tourism industry again, practitioners hope for more allowance”. (2021, January 13). Sinchew Daily.

“Minister of Tourism: Match to October, 109 Hotels and Guest House Closed”. (2020, November 23). Sinchew Daily.

“Ministry has strategies for tourism recovery”. (2020, September 13). New Strait Times.

“More hotels needed to quarantine returning Malaysians”. (2020, April 18). New Strait Times.

“National Tourism Policy aims to ensure industry's continuity in Malaysia, says Muhyiddin”. (2020, December 23). The Edge Markets.

“PM outlines plan to revive tourism industry with DPN 2020–2030”. (2020, December 23). New Strait Times.

“Prihatin Rakyat Economic Stimulus Package”. (2020, March 27). Ministry of Finance Malaysia.

“RM200 mil plan to rehabilitate tourism in Budget 2021 - Nancy Shukri”. (2020, November 18). The Edge Markets.

“Senior minister: Malaysians returning home from abroad to foot half of hotel quarantine bill”. (2020, April 20). The Malay Mail.

“Sustainable tourism income and quality tourists needed, said Nancy”. (2020, December 23). Sinchew Daily.

“Tour guides, undergrads benefit from Pahang government initiatives”. (2020, April 8). New Strait Times.

“Tourism Sector lost more than 100 billion, at least 4 years to recover”. (2020, December 23). Sinchew Daily.

“Tourism still allowed under 'strict SOP' as RMCO extended to Mar 31”. (2021, January 1). Malaysiakini.

“Tourism Malaysia ties up with Expedia”. (2019, August 21). The Star.

“Unemployment rate may be up to 14% - Kantar predicts toursim industry would be hardest-hit”. (2020, May 21). Sinchew Daily.

“Weekend trip to Bangkok? Not happening any time soon”. (2020, May 25). The Straits Times.

“Why is it so important for Malaysians to travel local post Covid-19?” (2020, April 18). The Star.

“World Health Organization declares the coronavirus outbreak a global pandemic”. (2020, March 11). CNBC.

“15 per cent of hotels in Malaysia may have to close operations”. (2020, April 26). New Strait Times.

“1.2 million To Boost Local Tourism, Datuk Nolee”. (2020, December 24). Sinchew Daily.

_____

1During “Conditional Movement Control Order” (CMCO) and “Recovery Movement Control Order” (RMCO) period, nationals are allowed to cross state and attend gatherings as the situation was eased at that stage.

Last Update: 27/07/2023