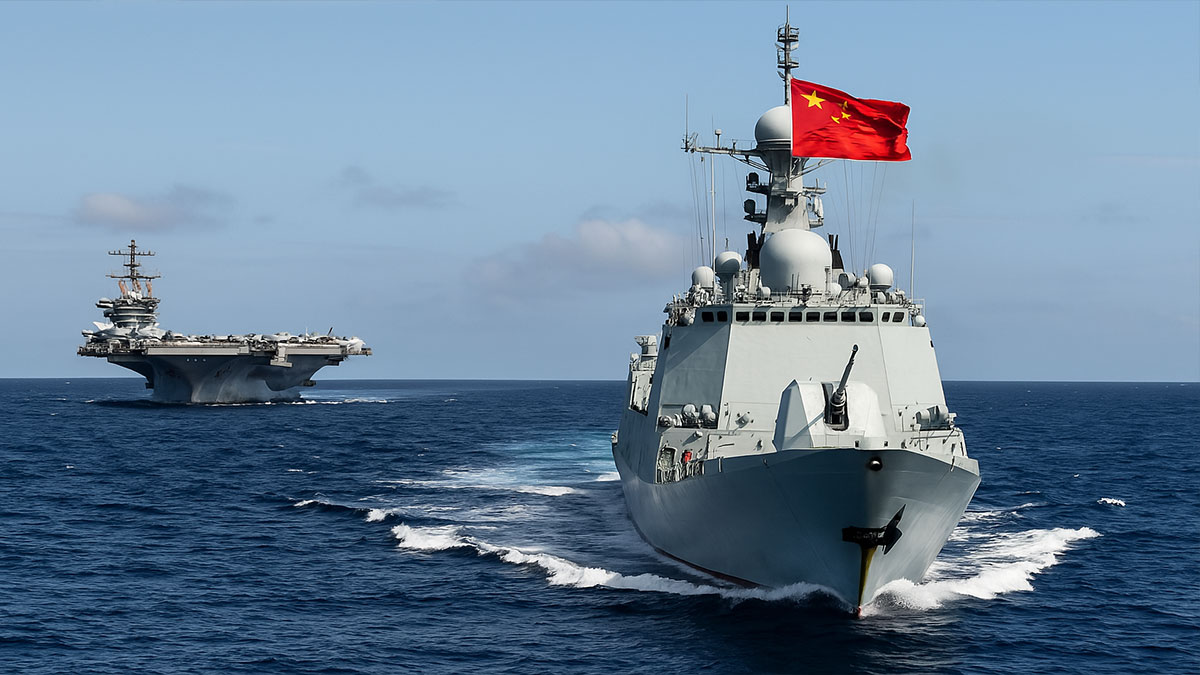

The Indo-Pacific has become the focal point of great power competition, where naval dominance is a decisive factor in shaping the regional balance of power. At the heart of this contest is the stark contrast between China’s surging shipbuilding capabilities and the United States’ struggles to maintain its maritime superiority. A closer examination of both nations’ shipbuilding capacities reveals the extent to which China is outproducing the United States, particularly in military vessels, with serious implications for regional security.

China's shipbuilding industry has grown exponentially since the 1970s, benefiting significantly from Japan’s Official Development Assistance (ODA)1, which facilitated technology transfer and modernisation of shipbuilding and steel industries. Through the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), Chinese engineers and managers trained in Japanese shipyards, while Japanese experts provided on-site guidance in China. Leading facilities such as Jiangnan Shipyard, which produces both civilian and military vessels, benefited from these collaborations, learning from firms like Mitsubishi Heavy Industries.2

China’s rise as a maritime power is driven by its rapidly advancing shipbuilding sector. The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is now the world’s largest navy by fleet size, with over 370 battle force ships, projected to exceed 435 by 2030.3 This expansion is facilitated by China’s extensive network of state-supported shipyards, many of which possess dual-use capabilities, enabling seamless transitions from commercial to military shipbuilding. Notable naval production hubs include Jiangnan Shipyard, Dalian Shipbuilding Industry Company, Hudong-Zhonghua Shipbuilding, and Guangzhou Shipyard International.

A critical factor in China’s shipbuilding supremacy is the synergy between state- owned enterprises and the military-industrial complex. The China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC) and the China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation (CSIC) merged in 2019 to form a behemoth that streamlines production and enhances efficiency.4 This integrated system enables China to produce warships at an unprecedented rate, with a capability that far surpasses that of the United States. In 2024 alone, China built more naval tonnage than the entire U.S. industry has since World War II.

China’s shipbuilding supremacy is further reinforced by substantial government subsidies, an abundant skilled workforce, and direct state oversight, ensuring rapid completion of naval projects. The efficiency of Chinese shipyards in producing advanced warships, including aircraft carriers, destroyers, and amphibious assault ships, starkly contrasts with the slower and costlier U.S. shipbuilding process. Jiangnan Shipyard, for instance, has successfully constructed the 003 Aircraft Carrier, Type 052D destroyers, and Type 055 cruisers.5

The U.S. shipbuilding industry peaked in the 1920s, once accounting for 22% of global shipping tonnage. The Merchant Marine Act of 1920, or the Jones Act, aimed to protect domestic shipbuilding but has contributed to long-term inefficiencies.6 Over the past century, fluctuating government subsidies, high labour and steel costs, and market uncertainties have led to a continuous decline in U.S. commercial shipbuilding.

By 2023, the U.S. Navy operated approximately 296 battle force ships—80 ships short of its projected requirement.7 Although plans exist to expand the fleet to over 350 ships by the 2040s, achieving this goal presents significant challenges. The U.S. has only a handful of operational shipyards capable of constructing large warships, a stark contrast to China’s vast production network. Additionally, the U.S. shipbuilding workforce has dwindled from 120,000 to about 72,000 over the past two decades.

Another major hindrance to U.S. naval expansion is the high cost and lengthy timelines associated with warship production. The construction of an Arleigh Burke- class destroyer, for example, takes roughly four years, whereas China can build a Type 052D destroyer in nearly half that time. U.S. shipyards are further burdened by bureaucratic inefficiencies, complex procurement processes, and a lack of coordination between government and private industries.

While efforts are being made to revitalize the U.S. shipbuilding sector— including initiatives to integrate commercial and military shipbuilding and invest in workforce training—these measures are unlikely to yield immediate results. The constraints on U.S. shipbuilding raise concerns about the Navy’s ability to sustain its forward presence in the Indo-Pacific, especially in light of China’s rapid fleet expansion.

The growing disparity in shipbuilding capabilities between China and the U.S. has profound consequences for Indo-Pacific security. China’s ability to rapidly produce and deploy naval assets enhances its capacity to enforce maritime claims, project power, and challenge U.S. naval dominance in key strategic waterways, such as the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait. Recent dual-aircraft carrier drills conducted by the PLAN underscore its expanding operational reach.8

Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy’s shrinking fleet and declining shipbuilding capacity hinder its ability to counterbalance China effectively. With global commitments stretching resources thin, Washington faces mounting pressure to reinforce its regional military posture through alliances. The AUKUS pact and QUAD initiatives— designed to enhance maritime security cooperation with Australia, Japan, and India— reflect a strategic effort to offset China’s naval expansion.

However, alliances alone may not suffice if the U.S. fails to accelerate shipbuilding and fleet modernisation. A prolonged inability to address industrial shortcomings risks ceding greater strategic space to China, allowing Beijing to shape the maritime order in the Indo-Pacific. Some argue that the U.S. could leverage the shipbuilding industries of allies such as South Korea and Japan—the world’s second and third largest maritime industries—to address shortfalls, but the effectiveness of such partnerships remains uncertain.9

The ongoing naval arms race between China and the United States is marked by Beijing’s ability to outproduce Washington in warship construction at an alarming rate. China’s state-backed shipbuilding sector, coupled with strategic investments and production efficiencies, has enabled the PLAN to expand at a scale unmatched by the U.S. Meanwhile, the United States grapples with shipyard limitations, cost overruns, and a shrinking workforce, all of which hinder its ability to compete in naval production.

As Alfred Thayer Mahan observed in The Influence of Sea Power upon History, “Whoever rules the waves rules the world.”10 This historical truism highlights the strategic importance of naval power. If the U.S. is to maintain its maritime pre- eminence in the Indo-Pacific, it must undertake a fundamental restructuring of its shipbuilding industry. Failure to do so will not only weaken America’s strategic position but also embolden China’s maritime ambitions, reshaping the regional balance of power for decades to come.

Footnotes:

1 Takagi, Shinji. 1995. From Recipient to Donor. International Finance Section Department of Econ Ton Univers.

2 Mingzi, Li. 2023. “What Has China Gone through to Become so Strong in Shipbuilding?” Cansi.org.cn. 2023. https://www.cansi.org.cn/index.php/cms/document/18575.html.

3 Rossi, Emanuele. 2025. “The Pentagon Report: China’s Military Rise and Its Implications for the West – Chinaobservers.” Chinaobservers. February 20, 2025. https://chinaobservers.eu/the-pentagon-report-chinas- military-rise-and-its-implications-for-the-west/.

4 Nouwens, Meia. 2019. “Is China’s Shipbuilding Merger on Course? .” IISS. 2019. https://www.iiss.org/ar- BH/online-analysis/military-balance/2020/09/china-shipbuilding-merger/.

5 Du, Harry. 2018. “Analysis of Jiangnan Shipyard | ChinaPower Project.” ChinaPower Project. December 17, 2018. https://chinapower.csis.org/analysis-jiangnan-shipyard/.

6 Potter, Brian. 2024. “Why Can’t the U.S. Build Ships?” Noahpinion.blog. Noahpinion. September 5, 2024. https://www.noahpinion.blog/p/why-cant-the-us-build-ships.

7 LaGrone, Sam. 2023. “Navy Raises Battle Force Goal to 381 Ships in Classified Report to Congress - USNI News.” USNI News. July 18, 2023. https://news.usni.org/2023/07/18/navy-raises-battle-force-goal-to-381-ships-in- classified-report-to-congress.

8 Luck, Alex. 2024. “China Conducts First Dual Carrier Op in South China Sea.” Naval News. October 31, 2024. https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2024/10/china-shows-off-elaborate-first-dual-aircraft-carrier-photo-op/.

9 Panella, Chris. 2025. “Naval Affairs Specialist Says Pacific Allies Might Just Have Answers to US Shipbuilding Problems.” Businessinsider.com. 2025. https://www.businessinsider.com/pacific-allies-may-have-answer-to-us- navy-shipbuilding-problem-2025-3.

10 Mahan, Alfred T. (1890) 2017. The Influence of Sea Power upon History 1660-1783. London: Forgotten Books.

Bibliography:

Du, Harry. 2018. “Analysis of Jiangnan Shipyard | ChinaPower Project.” ChinaPower Project. December 17, 2018. https://chinapower.csis.org/analysis- jiangnan-shipyard/.

LaGrone, Sam. 2023. “Navy Raises Battle Force Goal to 381 Ships in Classified ReporttoCongress-USNINews.”USNINews.July18,2023. https://news.usni.org/2023/07/18/navy-raises-battle-force-goal-to-381-ships-in- classified-report-to-congress.

Luck, Alex. 2024. “China Conducts First Dual Carrier Op in South China Sea.” Naval News. October 31, 2024. https://www.navalnews.com/naval- news/2024/10/china-shows-off-elaborate-first-dual-aircraft-carrier-photo-op/.

Mahan, Alfred T. (1890) 2017. The Influence of Sea Power upon History 1660- 1783. London: Forgotten Books.

Mingzi, Li. 2023. “What Has China Gone through to Become so Strong in Shipbuilding?”Cansi.org.cn.2023. https://www.cansi.org.cn/index.php/cms/document/18575.html.

Nouwens, Meia. 2019. “Is China’s Shipbuilding Merger on Course? .” IISS. 2019. https://www.iiss.org/ar-BH/online-analysis/military-balance/2020/09/china- shipbuilding-merger/.

Panella, Chris. 2025. “Naval Affairs Specialist Says Pacific Allies Might Just HaveAnswerstoUSShipbuildingProblems.”Businessinsider.com.2025. https://www.businessinsider.com/pacific-allies-may-have-answer-to-us-navy- shipbuilding-problem-2025-3.

Potter, Brian. 2024. “Why Can’t the U.S. Build Ships?” Noahpinion.blog. Noahpinion. September 5, 2024. https://www.noahpinion.blog/p/why-cant-the-us- build-ships.

Rossi, Emanuele. 2025. “The Pentagon Report: China’s Military Rise and Its Implications for the West – Chinaobservers.” Chinaobservers. February 20, 2025. https://chinaobservers.eu/the-pentagon-report-chinas-military-rise-and-its- implications-for-the-west/.

Takagi, Shinji. 1995. From Recipient to Donor. International Finance Section Department of Econ Ton Univers.

Article was originally produced for IFEMES.

Last Update: 06/04/2025