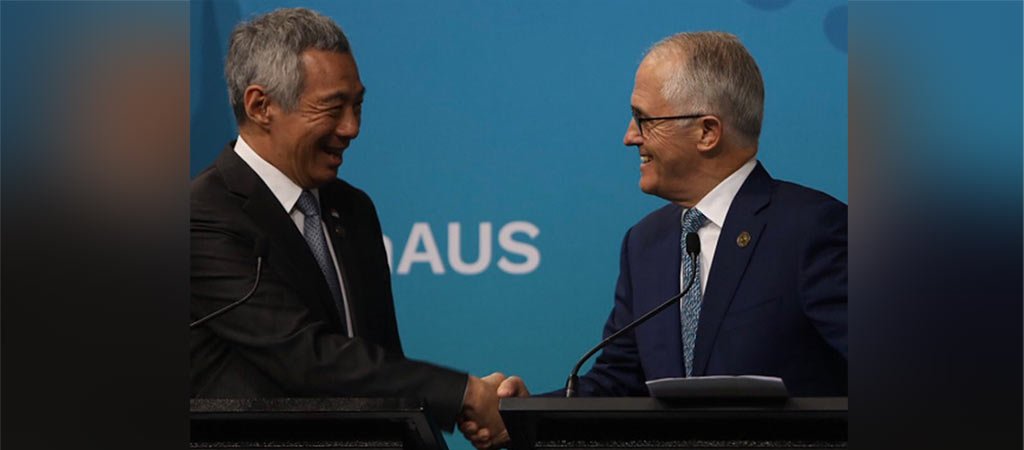

The ASEAN–Australia Special Summit attracted bipartisan Australian support, and was a success. We saw Malcolm Turnbull, in his carefully worded commentary and body language, engaging effectively with our neighbours. He understood the rhetorical need to declare our ‘steadfast commitment to ASEAN’, and in various economic, security and education areas Australia expressed a commitment to practical cooperation.

In reminding our guests that we have much to offer, we were developing a distinctively Australian engagement with Asia. This is the long game Australia has sometimes played in the past—and must play assiduously if we aren’t to become an increasingly lonely nation in a less America-dominated era.

Thus, the good news. However, listening to ASEAN reactions—including in the chatter around the edge of formal events—suggests the need for caution. The Australian media commentary, it might be argued, included several false leads.

First, some analysts became excited by the idea that Australia might join ASEAN. Former Indonesian Foreign Minister Marty Natelagawa called such an initiative a ‘distraction’. In fact, it would be counterproductive.

Rudolfo Severino, former Secretary-General of ASEAN, has said that Australians aren’t perceived to be ‘Southeast Asians’. Australian membership would require consensus approval, and a campaign to join would arouse negative as well as positive responses in Australia, as well as in ASEAN countries, damaging our engagement.

In economic and security matters there’s important common ground between Australia and our Southeast Asian neighbours—but there are also differences in policy objectives and political culture. The Rohingya crisis and Cambodian politics are danger areas, and the conspicuously absent Philippines president, Rodrigo Duterte, has a wider regional influence than many Australians would like.

Looking across the region, no country comes close to Australia in commitment to liberal values—and yet many Southeast Asians are proud of what their countries are achieving in economic and social development, and are unlikely to see Australian membership as a priority.

True, Australia was ASEAN’s first official dialogue partner back in 1974, but today ASEAN has many suitors. Japan, South Korea, the United States, Russia and India all hosted summits with ASEAN before we did—and Australia is now outmatched in both trade and investment.

Another reason for hesitation about Australia getting inside, rather than closer to ASEAN, is the contrast in diplomatic culture. The increasingly influential Sultan Nazrin of Malaysia, who gave the keynote speech at the lively Track 2 dialogue preceding the summit, stressed the significance of ‘mutual consultation’ and ‘consensus building’ as ASEAN’s ‘preferred methods for managing disputes and moderating differences’—and the ASEAN discomfort with ‘adversarial approaches’.

Australians may come to respect ASEAN methods, but this would require new levels of patience—as would working within the complex and often ritualised processes of ASEAN.

In addition to the issue of membership, another false lead was the proposal to unite ASEAN in some way with the developing Quadrilateral, which brings Australia together with the United States, Japan and India. Apart from its security dimension, this grouping is said to be planning to fund regional infrastructure ‘to counter the rising influence’ of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

The Quad has been promoted as a democracy-based venture, which immediately raises ASEAN suspicions. As Sultan Nazrin’s keynote address explained, ASEAN doesn’t discriminate on grounds of ‘political ideology and security alignment’, but ‘welcomes all political systems’. Thus, Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong warned that ASEAN doesn’t want ‘rival blocs forming or countries having to take sides’.

Even when talking of the reworked Trans-Pacific Partnership, Lee hoped that both China and America would eventually join. By contrast, the Australian leadership has been content to claim that in strategic terms we’re ‘joined at the hip’ with the United States.

ASEAN doesn’t approach China the way Australia tends to do today. It’s an exaggeration to say—as one newspaper did—that the ‘spectre of a rising China stalked’ the summit. Singapore is by no means the most pro-China country in the grouping, yet Lee described China’s aim to grow its influence as ‘legitimate’. Southeast Asia has very long experience of a powerful China and sees advantage as well as danger in its rediscovered paramountcy.

The South China Sea disputes are only one dimension of the relationship—and here too there’s an element of optimism, and patience. Australian commentators have overestimated the degree to which ASEAN is divided. Also, although Southeast Asians tend to welcome the presence of the United States and others in their region—and want to maintain the space for their engagement—it’s wrong to assume they favour confrontation.

Even in the case of the concept of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ we’ll have to argue hard that it isn’t a code-word for containment—nor the basis for a new regional architecture designed to challenge ASEAN’s structures.

An additional false lead, favoured by a few Australians, was the suggestion that we’re wasting our time on ASEAN, a slow-moving organisation that has failed to ‘stand up to China militarily’ and has been unable to solve the Korean crisis. These are unreasonable tests, and our prime minister was right to praise ASEAN as the ‘strategic convenor of our region’.

Institutions that Australia has favoured—The Asia and Pacific Council of decades ago, Rudd’s doomed Asia Pacific Community and even APEC—have prospered less than ASEAN-centred ones, and we have operated best when working with ASEAN countries (for instance, in the Bali Process). Competition between China and Japan prevented Northeast Asia from providing leadership, and ASEAN’s creative diplomacy hasn’t only promoted dialogue between these powers, but also brought the US, Russia and even North Korea into regional deliberations.

ASEAN remains our best option if we wish to build trust, not confrontation, in this rapidly changing region. What’s more, we already trade with ASEAN much more than with the US and even Japan—and the future potential is impressive. Prioritising relations with our nearest Asian neighbours will benefit—not damage—our relations with both Beijing and Washington. Far from undercutting our critical US alliance, the ASEAN priority enriches Australia’s international identity.

Anthony Milner is International Director of Asialink and co-chair of the Australian Committee of the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific. Image courtesy of the Prime Minister’s Office via Twitter.

* This article was first appeared in ASPI's The Strategist website.

Last Update: 17/01/2023