AEI-Insights - AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ASIA-EUROPE RELATIONS

(ISSN: 2289-800X); JANUARY, 2016; Volume 2, Number 1

Anis Bajrektarevica and Petra Posegab

aInternational Law and Global Political Studies

Vienna (Austria), EUROPE

Tel: +43 (0) 676 739 71 75

Email: anis@bajrektarevic.eu

bFaculty of Criminal Justice and Security

Ljubljana, Slovenia

Tel: +386041829763

Email : petra@moderndiplomacy.eu

Regions, rich in energy resources, continue to be of crucial interest to our carbon-powered world. Numerous factors summon concern, those such as international legal status, ownership rights, energy routes, transit corridors, state and corporate interests, environmental hazards, and the overall puzzle of energy diplomacy. Additionally, The Caspian is troubled with its specific complexities, some of which we list in our work. These include undefined legal status, territorial disputes, ethnic instabilities and vicinity to other hot spots, such as the turmoil Middle East and the more recently sparked conflict in Ukraine. Influenced by its geography, The Caspian is also of central interest for European energy security, although the supply chain from the region has been traditionally under Russian control. However, for the past decade or so, the EU has become increasingly ambitious in planning Caspian pipelines that exclude Russian territories; the Nabucco Pipeline project has been at the centre of these strategic efforts for a considerable amount of time. The Caspian is therefore also at the crossroads between grand and conflicting energy interests of Russia and Western Europe.

Caspian Basin, energy security, pipelines, geopolitics, international maritime law

Just as the rapid melting of the Polar caps has unexpectedly turned distant and dim economic possibilities into viable geo-economic and geopolitical probabilities, so has the situation emerged with the unexpected and fast meltdown of Russia’s historic empire, the Soviet Union, and its economic ties to The Caspian Basin. Once considered as the Russian inner lake, The Caspian has presented itself as an open sea of opportunity, literally overnight. This opportunity exists not only for the new, increased number of riparian states, but also for the belt of neighboring states, both old and new, as well as for other interested states, internationally.

The interests of external players range from the rhetorical to the geopolitical, and from the antagonizing of political conditionality and constraint to more pragmatic trade-offs between political influence and gains in energy supply. We thus identify the three most important categories of interest in The Caspian; The first are the energy-related economic and political interests. These refer to the exploitation of gas and oil resources hidden in The Caspian. The second are the non-energy related economic interests, such as extensive fishing options and the costly caviar of The Caspian Sea. The third is The Caspian’s strategic position. Its location not only constitutes one of numerous European-Asian-Middle Eastern crossroads, but also offers various avenues for setting future pipeline routes that contribute to larger geostrategic and geo-economic considerations (Zeinolabedin and Shirzad, 2009).

In such an interest-driven set of conflicts, we cannot neglect the power and influence of large trans-national corporations which influence the region’s stability, equilibrium of interests, and policy-making processes. We thus hereby refer to non-state players such as organized radical Islamic groups, organized crime groups, and international and nongovernmental organizations concerned with human rights, democracy building, and ecological issues. Additionally, let us not disregard big consumers such as China, India, or the European Union (EU) that are driven by their own energy imperatives to improve their energy security as well as diversify their supplies, modes, and forms over the long term. Striving for energy security is, relative to demand, of utmost importance in relation to the geopolitics of energy in The Caspian.

On the promise of these allegedly vast and mostly untapped oil and natural gas resources, The Caspian is witnessing The New Grand Game—a struggle for dominance and influence over the region and its resources, as well as transportation routes. Notably, The Caspian basin is a large landlocked water plateau without any connection to outer water systems. Moreover, the former Soviet republic states of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan have no direct access to any international waters. Thus, pipelines remain the principle mode of transportation and delivery of carbonic fuels, creating yet another segment for competition and

sources of regional tension as the three riparian states depend on their neighbors for export routes. Due to both the unresolved legal status of the basin, as well as to the implications of its resources for the EU energy security, numerous new pipeline constructions and expansion projects have been proposed but remain unrealized. For the EU, the most important of these was the Nabucco pipeline, which, although not fully guaranteed, served as hope for energy reduced dependence on Russia. The goal is becoming additionally more relevant due to ongoing crises in The Ukraine and to the accompanying process of alienation from Russia, suggesting questionable future results.

In what follows, then, the paper, will consider the geopolitical, legal, and economic features of The Caspian Theater, complex interplays, and its possible future outlook. We will reflect in detail on the interests of the regional and global players involved, and on the very complex issue of the undeclared legal status of The Caspian, and the consequences this status quo holds for the concerned parties. In addition, the paper will emphasize the importance of the most notable current and planned pipeline projects, and their effects for EU energy security. Finally, the paper will describe future options for pipeline diplomacy in the region, and the implications of this diplomacy not just for the EU but also for the Caspian wider region.

The Caspian Water Plateau

The Caspian is the world’s largest enclosed body of salt water, approximately the size of Germany and the Netherlands combined. Geographical literature refers to this water plateau as a sea, or the world’s largest lake that covers an area of 386,400 km² (a total length of 1,200 km from north to south and a width ranging from a minimum of 196 km to a maximum of 435 km), with a mean depth of approximately 170 meters (maximum southern depth is at 1025 m). At present, the Caspian water line is some 28 meters below sea level (median measure of the first decade of the 21st century). The total Caspian coastline measures at nearly 7,000 km, shared by five riparian (or littoral) states.

The legal status of this unique body of water remains unresolved in whether the Caspian is a sea or lake. As international law distinguishes lakes from seas, the Caspian should be referred to as a water plateau or the Caspian basin. However, The Caspian is both a sea and a lake. Northern portions of the Caspian display characteristics of a freshwater lake, due to influx from The Volga, The Ural River, and other smaller river systems from northern Russia. In the southern portions, where waters are considerably deeper but without major river inflows, salinity is evident and The Caspian appears as a sea.

The Inner Circle

The so-called Inner Circle of The Caspian Basin consists of five littoral states—namely Russia, Iran, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan—sharing the common coastline. These have an asymmetric constellation and can be roughly divided between the two traditional states of Russia and Iran, and the three newcomers Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan. This division corresponds with that only Iran and Russia have open sea access, while the other three countries are landlocked, as The Caspian itself is a landlocked body of water.

In addition to five littoral states, and correspondingly five different perspectives on The Caspian, the region is home to numerous territorial disputes, while maintaining absolute geopolitical importance to its respective littoral states and beyond. The additional layer of complexity represents the unsolved legal status, while its resolution drifts between an external quest for the creation of special international regimes and the existing United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The dynamics of the respective littoral states display the following three traits; dismissive, assertive, and reconciliatory interests. A dismissive interest refers to eroding the efforts of the international community and external interested parties for the creation of the Antarctica-like treaty by keeping the UNCLOS referential. An assertive interest refers to maximizing the shares of the spoils of partition by extending the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and continental shelf as to divide most, if not the entire body of water, among only the five. A reconciliatory interest refers to preventing any direct confrontation among the riparian states, over the spoils, by resolving claims without arbitration from third parties (Bajrektarevic, 2011).

Russia

Only a negligible part of Russia’s extensive reserves appear to be located at The Caspian Basin, . Therefore, Russia has adopted a strategy of involvement in the energy businesses of the other, better-endowed riparian states, employing strategies such as joint resource development and the granting of access to the Russian oil and gas pipeline system. The main players in this field are the state-owned companies Gazprom, Rosneft, and Transneft, as well as numerous large private energy enterprises such as Lukoil, Sibneft, or Yukos (Crandall, 2006).

In light of the loss of economic influence in The Caspian after the dissolution of the Soviet Union – influenced by an overwhelming preoccupation with preserving the strategic influence in the region – Russia’s views dramatically shifted in the 2000s, from politico-security aspirations to largely economic goals. To this end, Russia turned to bi- and multilateral agreements with Caspian littoral countries so to secure its economic interests in the basin. With its unique policy, labelled common waters, divided bottom, it moved closer to the Kazakhstani/Azerbaijani stance, following the principle of dividing the seabed into proportional national sectors, aligning with the UNCLOS principle. Concurrently, Russia maintained a common management of the surface waters, preserving free navigation and common ecological standards for all littoral states, and thus partly following the lake principle by excluding the international community. With this division, Russia would receive eighteen and a half percent of The Caspian seabed, while Kazakhstan would receive twenty-nine percent, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan approximately nineteen percent, and Iran would be left with fourteen percent. Due to these efforts, Russia agreed upon the division of the northern part ofThe Caspian with Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, while still strongly affirming that the five-party consensus continues as the only path to a final decision on the legal status of The Caspian (Von Geldern and Zimnitskaya, 2010). Although this agreement presents a positive sign for the future, its major downside suggests a strong dependency on dependent on good relations between the littoral states, subsequently effecting a need to acknowledge the geopolitical realities of The Caspian. We must also consider the Iranian defiance of this solution since it diminishes its political and economic role in the basin, leaving the country with the smallest share and deepest waters. The division is illustrated in Figure 1.

Regarding intra-regional relations, Russian concerns about the influence of Turkey, China, The EU, and The US in the Caspian Basin have increased recently due to the eagerness to regain its role as a major power. Above all, the emergence of Azerbaijan as a major ally of the West has effected dismay in Moscow. As for Iran, the historically adverse relationship has improved in some areas as the two powers still share a number of mutual interests in the Caspian Basin. Examples of this include the opposition to growing Western interference in regional affairs, and the proposed construction of a trans-Caspian pipeline (Dekmeijan and Simonian, 2003).

Iran

Despite ranking among the world’s leading oil producers and second largest producer of natural gas, Iran’s share of the local oil and gas reserves is negligible, similar to Russia. Moreover, foreign direct investment (FDI) in the energy sector has been hampered due to continuous conflicts with the West over nuclear issues (Crandall, 2006). However, because of its status as a regional power, as well as its unique geographic position between The Caspian basin and The Persian Gulf, Iran remains an attractive transit country. This geographical advantage also grants it power and a wide range of possibilities for gaining influence as a Caspian littoral state.

Foreign policy priorities have been affected by Iran’s past dominance, as well as the religious ties it has with the Republics of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan. However, these newly independent states (NIS) see Iran’s potential in cheap transit routes for oil and gas rather than the Iranian advantage. Of greatest concern are Iran’s relations with Azerbaijan, hampered due to Azerbaijan’s westward cooperation on energy matters (Dekmeijan and Simonian, 2003). Additionally, significant also becomes the great divide between the two countries when defining the legal status of The Caspian. Initially following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Iran strongly asserted that Azerbaijan was, along with other former republics of Soviet Union, a successor to all the treaties signed between Iran and the Soviet Union. Although never fully deviating from this position, Iran, along with Russia, was also a strong supporter of the condominium solution. However, when Iran lost Russia as an ally on this matter due to Russia’s efforts to form a closer bond with neighboring Azerbaijan, it opted for the lake solution of The Caspian, which remains as Iran’s official position today. Azerbaijan, alternatively, has greatly defied all these positions and is lobbying for the Caspian to become subject to the UNCLOS treaty. This would allow a diminished role for Iran in The Caspian, along with the realistic threat of bringing foreign military vessels into The Caspian and onto Iranian borders.

Azerbaijan

Heavily dependent on the oil sector, the State Oil Company of The Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR) was created to provide benefit from abundant hydrocarbon resources in the Caspian Sea. Subsequently, foreign SOCAR partnerships have attracted considerable FDI to the region (INOGATE Oil and Gas Directory, 2003-2004). By 2010, and after signing the so called Contract of the Century with thirteen world leading oil companies in 1994, an amount of eight billion dollars had been invested into exploration and development operations in the sectors of The Caspian that belong to Azerbaijan, according to UNCLOS provisions. An additional one-hundred billion is expected to be invested in the next twenty-five to thirty years (Von Geldern and Zimnitskaya, 2010).

Azerbaijan has been very vocal on defining The Caspian as a sea and therefore subject to international law, a ruling from which Azerbaijan would benefit greatly. The continuous lobbying for this solution becomes evident given that economic stability has assisted Azerbaijan to deter its powerful neighbors Russia and Iran, and to sustain sovereignty as well as to keep alliances (Von Geldern and Zimnitskaya, 2010).

Azerbaijan’s goal has also been to maintain a balance between Russia and the West. However, of concern are the unresolved conflicts with Armenia over the status of The Nagorno-Karabakh province and fragile relations, mostly due to pipeline disputes with Turkmenistan (Dakmeijan and Simonian, 2003).

Kazakhstan

Holding the greatest share of Caspian oil in its national sector, Kazakhstan’s foreign policy is heavily influenced by its dependence on Russia as a primary energy transit route. The growing inflow of FDI from China signals the rising importance of cooperation with The East (The Economist, 2007). Due to the vast energy resources in its possession, Kazakhstan’s decision regarding energy export routes is crucial for the stability of the current power game in The Caspian. The country has three options for exporting its energy reserves. The first is the expanding of the existing route through Russia to the Black Sea coast (EIA, 2003). The second is the transporting of additional oil into the western Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) through the Aktau-Baku subsea pipeline (Marketos, 2009). The third option is the raising of the importance of the energy flow to The East through the Kazakhstan-China pipeline (EIA, 2003).

Turkmenistan

Recent developments have marked a new era with respect to Turkmenistan’s position in the energy game. With newly inaugurated Chinese and Iranian pipelines and pledges to supply the Nabucco pipeline, the country has not only diversified its supply routes but also offered central Asian countries the opportunity to lessen their dependence on Russia as a major energy supplier (BBC, 2010). Turkmenistan was also the first country in The Caucasus region to secure an energy contract which completely bypassed Russia. This was done through the Korpezhe-Kurt Kui pipeline, supplying Turkmeni gas to Iranian markets. In the aftermath of the Korpezhe-Kurt Kui project, Turkmenistan became extremely ambitious in terms of constructing new energy routes such as the proposed East-West pipeline, the Trans-Caspian pipeline, and the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline (EIA, 2012).

The Outer Circle and Other External Actors

Other players from the international community have been able to enter the Caspian game following the collapse of the Soviet Union. The three former members of the Soviet Republic were in desperate need of technology and capital so to exploit the hidden Caspian resources; the outside involvement was therefore seen as crucial for developing drilling and exporting capabilities, and also for distancing Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan from Russia. The Caspian basin is landlocked, therefore it is dependent upon pipelines and shipping through neighboring states so to reach consumer markets. Upgrading old Soviet pipelines and constructing others became pivotal for the economic stability of the region and it also allowed major strategic planning of these new pipeline routes. The three post-Soviet Caspian littoral states were not very powerful in regional, and more so global, terms. Newly independent, with weak militaries, barely functioning economies, and great prospects for domestic and external conflict, these states offered targets for other interested parties looking to exploit these circumstances (Kubicek, 2013).

With regards to the transshipment of hydrocarbons to the international market, the importance of the interests and the state of political environment in countries such as Georgia, Armenia, Turkey, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, India, and Pakistan, commonly referred to as the Outer Circle, requires mentioning. At the beginning of the energy hype around The Caspian, Turkey indicated its interest in exploiting its culture. This becomes more sensible considering that the Azeris, Turkmen, Kazakhs, and Uzbeks are all of Turkic heritage, and Turkey’s status as a modern, successful state could be utilized to gain major influence in the region. However, this perception has been far too optimistic; although Turkish construction firms seem to do well securing business in the region, Caspian states seem to prefer Russian, American, or European investors when it comes to investment and major energy projects. An important aspect for Turks is the BTC pipeline, which connects Turkey to the Caspian region. Nevertheless, most of the country’s energy needs are still met through pipelines from Russia, most notably The Blue Stream (Kubicek, 2013). With the suspension of the Nabucco (Nabucco- West) and recently, the South Stream Project, it has become evident that Turkey could play a much more crucial role in the future of pipeline diplomacy. For now, both The EU and Russia are suggesting a gas route through Turkey: EU sans Russia, with a starting point in Azerbaijan and Russia and with a stream of gas flowing from Russian fields, through Greece and Turkey. We have yet to witness which Southern Corridor strategy will be implemented. What is clear, though, is that Turkey gained greatly in its starting position because of the zero-sum gaming process between Russia and the EU, therefore, its expectations of being an important (pivotal) transit country may become a reality in the near future. Also significant to the competition in The Caspian are India and Pakistan’s growing energy needs. They have both backed the proposed TAPI pipeline, although the prospects for this pipeline seem dim in the foreseeable future. Furthermore, India has a vivacious cooperation with Iran in the field of gas supply; it gained rights to develop two Iranian gas fields and is in the midst of discussing a pipeline route from Iran that would traverse Pakistan (Kubicek, 2013). Iran undoubtedly represents a critical area of interests for India regarding its energy security, for it provides the country with shorter supply routes without major choke-points in between. The invigorated India-Iran strategic partnership from 2003, since it diminished due to US interference, would also be beneficial not just for India’s energy and Iran’s economic security, but also for the strategic balance and security enhancement of the whole region. Both India and Iran are similarly concerned in relation to issues such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, and recently, ISIS (Kapila, 2014).

Additionally, with regards to global actors such as The United States, The European Union, China, and Japan, the interest in The Caspian region can not only be limited to promoting general political stability and seeking access to Caspian oil and gas resources, but extending the view that Caspian states are a new potential market for western products and The FDI.

The United States has managed to gradually insert itself into the region. Initial involvement predominantly included investments made by major American corporations that gained substantial percentages in large-scale projects, mainly in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. Empowered by this, The US slowly became more ambitious. In accordance with its struggle to keep the vision of the unipolar world alive and relevant, it introduced a new important strategic goal for The Caspian; drawing pipeline routes that would completely bypass Russia and therefore diminish its influence in the region, but the “events have not transpired as those in Washington hoped or those in Moscow feared.” (Kubicek, 2013) Russia’s strategic influence did not dissipate, and besides Azerbaijan, The US has no other major ally among The Caspian littoral states. However, regarding strategic alliances in the countries surrounding The Caspian riparian states, the contrary is true.

China has moved from a somewhat silent presence during the time immediately following the collapse of the Soviet Union, to a more active involvement in recent years. Much like in Africa or The Middle East, this involvement is predominantly powered by the vast energy needs of the country. Also similar to Africa and The Middle East, China has high prospects for success because it seems like a less threatening partner than Russia or The US, not to mention the absence of historically denoted relations. It first managed to enter the region through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which has stretched from having predominantly security-oriented goals to being an energy-concerned forum, thus effectively introducing China into the energy politics of the region. Central Asia and the Caspian Basin are also part of China’s policy of the New Silk Road, stretching from China to Rotterdam, Netherlands. The concept of a New Silk Road is, much like the ancient one, envisioned to be an economic belt, an area of economic cooperation, a vision of China for the interdependent economic and political community spanning from the shores of The Pacific to the Western European sea (Tiezzi, 2014). At the moment though, China is mostly present in the Kazakhstani oil sector and the Turkmenistan gas sector. Also, we must consider the collision of Chinese energy security needs and the Iranian search for new energy partners after the harshening of Western sanctions due to the Iranian nuclear program. Both China and Iran have gained greatly with this enhanced cooperation; China with securing more energy supply deals and Iran with preserving its state of economic development and stability.

Innumerable negotiation rounds have been held in order to determine the legal framework applicable to the Caspian Sea. Affecting both the development and ownership rights for gas deposits, the implications reach to topics such as environmental protection, navigation of the waters, and fishing rights.

Historical Developments Prior to 1991

The year 1991 not only represents a key date in world history, but also left a deep imprint on the Caspian Basin. After all, the number of riparian states increased from two to five virtually overnight, following the disappearance of The Soviet Union. The first sources addressing the legal status of the Caspian Sea date back to the 18th and 19th centuries, when the first treaties between Russia and Persia were concluded, de facto establishing the beginning of Russian geopolitical supremacy in The Caspian region (Raczka, 2000). With the creation of The Soviet Union, a new legal framework, the Treaty of Friendship, was negotiated in 1921, declaring all previous agreements void (Mehdiyoun, 2000). Following the 1935 Treaties of Establishment, Commerce, and Navigation; the 1940 Treaty of Commerce and Navigation; the 1957 Treaty on border regimes and subsequent Aerial Agreement; the initial obligations of the 1921 treaty were further reiterated, establishing consensus over matters previously not covered.

However, with the collapse of The Soviet Union, the legal validity of the existing legal framework prior to 1991 was seriously challenged, and to a great extent obsolete, no longer reflecting the realities within the region. The Caspian Basin has become a unique multinational mixture of economic, political, energy, and environmental concerns; where the division in any way has, for now, proven to not balance properly between the areal and utility claims of the parties in conflict (Oleson, 2013). But as the exploitation of the resources hidden in The Caspian became a reality in the 2000s, the states chose to distance themselves from the international regime and to seek other solutions under which they can divide their respective energy reserves. But the lack of utilization of international law inevitably means more maneuvering space for self-interested power play (Von Geldern and Zimnitskaya, 2010).

Present Alternative Legal Options and their Implications

Following the increase in the number of Caspian littoral states, calls for alternative legal options were made, most importantly either determining the legal status of the Caspian Sea or insisting on the condominium approach. Classifying The Caspian Sea as a sea would bring forth the application of the 1982 UNCLOS. Following this action, The Caspian Sea would be divided into respective corridors, determining the applicable rights and obligations both for littoral states and the third parties (Janis, 2003). That would essentially divide The Caspian into three parts. First, there are the territorial waters stretching twelve nautical miles from the shore. Second, there are the 200 to 350 nautical miles of continental shelf depending on the configuration of the continental margin. Third, there are exclusive economic zones (EEZs) that extend from the edge of the territorial sea waters up to no more than 200 nautical miles into the open sea. Within this area, the coastal state has exclusive exploitation rights over all natural resources. While territorial waters grant full state sovereignty, the EEZs grant sovereign rights with which to exploit resources to a certain state, but not sovereignty over the waters of the EEZ.

This division, considering the fact that the Caspian width does not extend 435 miles, would mean different state economic zones and continental shelves would overlap, giving way to interstate bargaining. According to UNCLOS, the “delimitation of the continental shelf...shall be effected by an agreement on the basis of international law...in order to achieve an equitable solution” (Aras and Croissant, 1999). In this process, the most powerful states in the area would have the advantage in the bargaining. Considering that UNCLOS has been accepted and ratified, only Russia faces the complexity of defining the status of the Don-Volga system and the incompleteness The UNCLOS solution offers for the Caspian.

Conversely, classification of The Caspian Sea as a lake is complicated both by the absence of international convention on the issue and the lack of international practice, even if covered by customary law. The most common practice on the matter is the division of the water plateau into equal portions, inside which states exercise full sovereignty. In the sovereignty sense, drawing a border on an inner water surface is similar to drawing land borders. In comparison to the solution under the provisions of UNCLOS, the division of national sectors under this principle would grant the states a greater degree of control (Dekmeijan and Simonian, 2003) and leave no room for political bargaining. This also closes the door to the international community, foreign trade, a military presence, and large petroleum companies.

The final option, condominium status, defined as conjoint ownership over a territory, is usually seen as temporary in nature and used only as a last resort. This solution for the Caspian was initially urged by Russia and Iran, which was not sufficient to approve as the final solution for the division of the Basin (Raczka, 2000). The newcomers to the Caspian membership: Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan, have been advocating strongly against this idea given their relatively long Caspian coastal lines and heavy dependence on Caspian produced energy. Currently, the condominium option seems the least plausible of all the proposed solutions. After Russia’s change of heart regarding the condominium issue. due to attempts to improve the relationship with Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, Iran was left without an ally. Keeping this in mind, Iran strongly supporting the lake solution because it still rewards Iran with a considerable portion of the Caspian (Oleson, 2013).

Present and Future Outlook

As of the new millennium, the already mentioned important shift took place in the legal division of The Caspian Basin. The northern part of the seabed was de facto divided between Russia, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan in 2003; however it is unclear whether Iran and Turkmenistan will compromise on the issue. Considering the frequent border disputes between Azerbaijan and Iran in the recent past and the absence of de jure division of the Basin, the situation needs unanimous settlement in order to avoid future conflicts and to attract foreign investment.

The most publicized trans-Caspian initiatives – the twenty-third meeting of the Special Working Group on The Caspian Sea in 2008 and The Caspian Five Summit in 2010, both held in Baku – have, contrary to expectations, failed to deliver a feasible solution. An agreement regarding the security issues was signed in November 2010. However, the issue of the legal status of The Caspian was once again postponed. The 2010 Baku summit reflected the status quo, and focused on pipeline developments in Nabucco, trans-Caspian initiatives, and future revenue possibilities. As a result, the five states left the territory and resource issues unsolved (Pannier, 2010). Despite these failures, an agreement was reached among all five littoral states by the end of September 2014. Iran and Russia successfully lobbied to reach a unanimous agreement about the inadmissibility of a foreign military presence in The Caspian, thereby ruling out any possible future deployment of North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) forces (Dettoni, 2014). This signals the aspiration of all parties involved in finding common ground on the delimitation matter. Although an agreement on this has not yet been reached, evidently no NATO flag will be flying above Caspian waters, which is an important geostrategic victory for Russia and Iran. The decision comes at a fragile time for both countries in question; the civil war in Ukraine has severely damaged Russia’s relations with the West, and Iran is still in the midst of very harsh sanctions due to its nuclear program.

Energy Reserves and Transportation

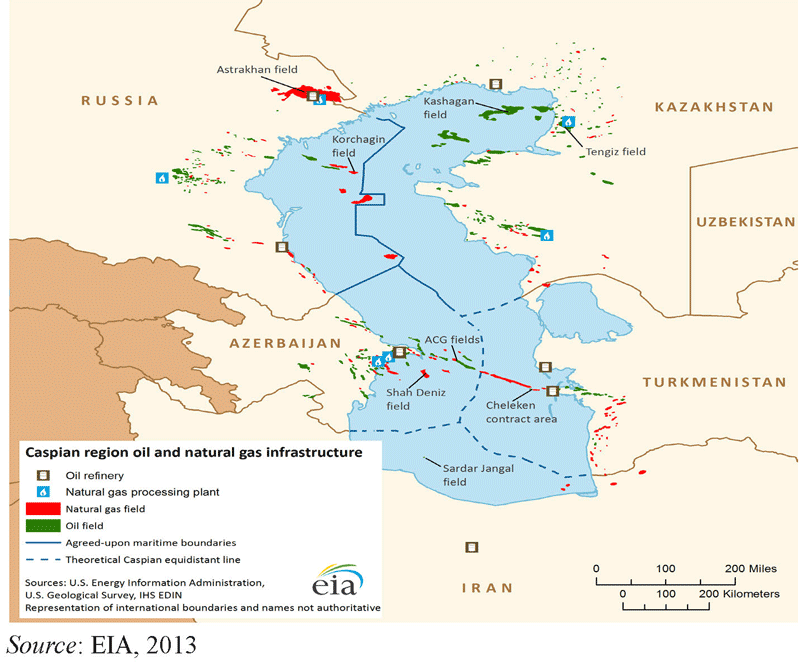

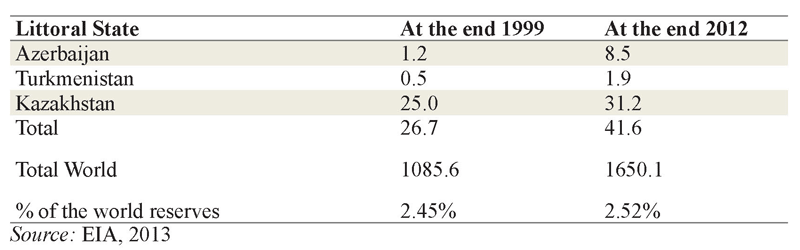

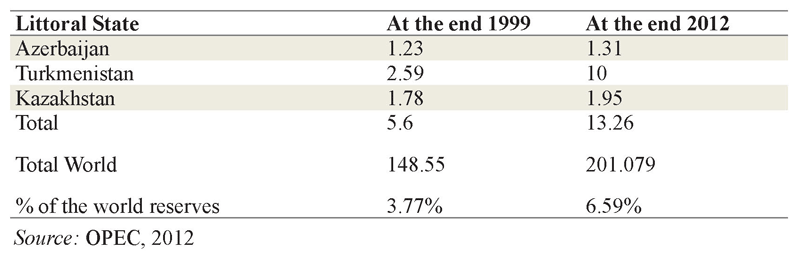

The Caspian energy reserves, concentrated primarily in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan, can have a disruptive effect on the global energy market. As Tables 1 and 2 show, in 2012 The Caspian share constituted 3.4 percent of global oil production, and 20 percent of total world gas production. However, with the increase of Azeri and Kazakh oil production, and Azeri gas production, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan will increase their importance in export markets (BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2013).

Due to the landlocked nature of The Caspian Basin, the NIS depend on at least one adjacent country in order to export oil and gas. Traditionally, the infrastructure has been dominated by Russian state-owned pipeline monopolists. However, this contradicts the needs of the NIS, which seeks energy independence for implementing energy deals (Goldwin and Kalicki, 2005). There are important pipelines that are not controlled by Russia, most notably the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) oil pipeline and the parallel gas counterpart South Caucasus Pipeline (SCP), also known as Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum (BTE). Upon its opening, the BTC pipeline was regarded as the largest exporting pipeline in the world, spanning over 1,040 miles of terrain. The construction of the pipeline is regarded as unique for connecting The Caspian to The Mediterranean Sea. Europe gained access to the heart of Central Eurasia upon the completion of the BTC. This strategic economic cooperation also explains why a partnership with NATO and The EU is one of the highest priorities for the newly independent Soviet Republics (von Geldern and Zimnitskaya, 2010). The westward extension of the SCP to Central Europe, and construction of a trans-Caspian oil or gas pipeline are of great interest to the West, especially The EU, to transport Kazakh and Turkmen reserves via the BTC and SCP. Lastly, due to heavy reliance on the oil and gas sectors in the economies of five Caspian states, prudent administration is of utmost importance. For example, stabilization oil funds were set up in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan to retain profits. However, due to corruption, these funds have failed to achieve their goals (Crandall, 2006).

These large construction projects often lack proper regulations and oversight. There are two ways for managing such regulations: inter-governmental agreements (IGA) between the countries directly involved or a series of host government agreements (HGA) between the states in question and the corporation-led consortium. These agreements were originally designed to reduce the risks of investing in unstable regions, and to avoid inefficiencies associated with local government corruption. Both solutions have been liable to criticism; IGAs due to the above mentioned lack of prudent administration and corrupt governments and HGAs due ro their tendency to take precedence over domestic legislation. HGAs are part of international investment agreements under international law, usually of extremely volatile nature; it is standard procedure to include a clause, stating that the agreed-upon-standards are not static but will evolve over time (Amnesty International, 2003). This essentially allows oil interests to surpass standard legislative regimes on oil and gas exploitation and on environmental protection issues. Additionally, the host governments are not allowed to challenge the decisions made in the name of “evolving conditions” due to the possible damaging “effects on the economic equilibrium” of the project, therefore representing a clear danger to national sovereignty (von Geldern and Zimnitskaya, 2010).

With the intention of meeting energy policy priorities, The EU has identified cooperation with The Caspian region as one of top goals. The general legal framework governing the political, legal, and trade relationships with Caspian states is The Partnership and Cooperation Agreements (PCA); with the exception of Iran. With the aim of building a stronger presence in the region, The EU has initiated several collaboration platforms: Transport Corridor Europe-Caucasus Asia (TRACECA) in 1993, Interstate Oil and Gas Transport to Europe (INOGATE) in 1995, The Energy Charter Treaty in 1997, and The Baku Initiative in 2004 (European Commission, 2006).

In regards to energy security, the risks of an over dependence on Russia as a primary source of both oil and natural gas supply became especially apparent after a series of disruptions of gas deliveries to Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltic States (US Library of Congress, 2006). Moreover, as significant stakes in several European energy companies have been acquired by Gazprom, an EU goal to diversify among suppliers is anticipated (Baran, 2007). Functioning markets, diversification of sources, geographical origin of sources, and transit routes were outlined in the EU action plan titled, Energy Policy for Europe (European Commission, 2006).

In addition to The EU, the presence of other global players such as Japan, China, the US, and Turkey must also be considered. Japan’s position in the region can be seen more as a provider of development aid, but the presence of US and China signal the growing need for energy to satisfy their increasing demand.

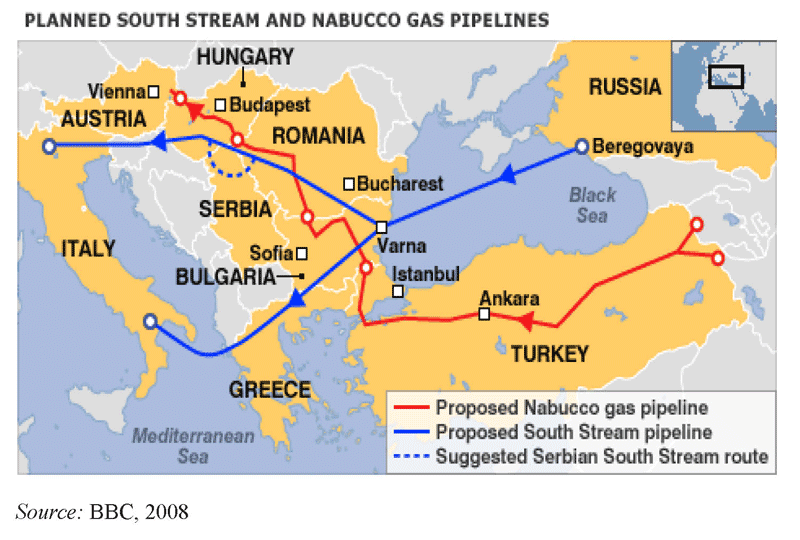

Nabucco was the natural gas pipeline project designed to connect Caspian resources with European markets, and has enjoyed full support from The EU as a means to diversify energy supply. Stretching from Turkey to Hungary while crossing Romania and Bulgaria, the initial plan envisioned transporting natural gas from Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Iran, Iraq, and Egypt. Given the thirty-one billion cubic meter (bcm) maximum capacity of Nabucco, the project could potentially contribute 4.4 percent of the total required gas supply.

In the first phase of the project, Azerbaijan has agreed to feed the pipeline with eight bcm of gas. The second phase plans to introduce gas from other Central Asian countries, while the third phase would provide a steady gas flows from Iran, Iraq, and possibly Egypt (Baker and Rowley, 2009). This pipeline posed a strategic rivalry to Russia’s proposed South Stream Pipeline because the two pipelines target the same markets and follow extremely similar routes. Three out of five countries envisioned to be along the Nabucco pipeline are also part of The South Stream proposed pipeline, all of which is clearly recognizable in Figure 2.

The financing of the two projects also merits examination. The Nabucco pipeline is designed to be privately financed, and therefore has to demonstrate its commercial value. The Russian firm, Gazprom, will never have a problem with financing in accordance with Moscow’s strategic goals (Marketos, 2009). Additionally, both projects have been facing criticism for several reasons. Russia has accused the Nabucco deal of being politically motivated and has even accused the company of artificially inflating the commercial value of the project. Furthering Russia’s claims, Nabucco was given an official exemption from EU competition rules in 2008 (Downstream Today, 2011).

Aware of the EU deal, Russia has begun development of the South Stream and North Stream projects, both designed to deliver gas to European markets. The South Stream’s initial output was projected to reach the markets in 2015 (The South Stream Project, 2014). But pipeline diplomacy proved unpredictable, and political bargaining halted the project, pronouncing it dead in late 2014. The pragmatic reasons for this decision were the continuous obstructions, posed by the Bulgarian government (which many believe were orchestrated and supported by Brussels). Henceforth Russia declared her withdrawal from the South Stream pipeline, and immediately started focusing on Chinese markets,as well as securing new deals with Turkey (Micalache, 2015).

While initially planned for construction in 2009, Nabucco has also faced challenges both on the investment and supply sides. Even though the 7.9-billion-dollar project secured promises of five billion dollars in loans from the World Bank in 2010, The European Investment Bank, The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, RWE of Germany, and OMV of Austria have all announced their decision to postpone their investment in 2009. Furthermore, the Azeri contribution was supposed to account for approximately one-third of the pipeline’s capacity, but the financing ultimately proved elusive. In order for the pipeline to be fully viable, Nabucco is in need of additional suppliers among the NIS (The Economist, 2010).

But the Nabucco pipeline received a damaging blow in 2012 when the proposed pipeline route was reduced more than half, from the original 3900 miles to 1300 miles, due to the substantial and previously uncalculated for financial costs and shifting governmental support in host countries (Natural Gas Europe, 2012). This meant that the Eastern section of the pipeline was terminated, making way for the Turkey-Azerbaijani-financed Trans-Anatolian pipeline (TANAP). The remaining part was afterwards known as the Nabucco-West. But even this reduction could not save the project from receiving a lethal blow in June 2013, when the Azeri Shah Deniz Consortium chose the competing Trans-Adriatic pipeline (TAP) instead (Del Sole, 2013). After the decision was made public, the chief executive of the Austrian energy company, OMV, told the media that the Nabucco pipeline was over for them, effectively ending the dream of many high-level politicians in the EU energy sector. A decade of planning was abruptly finished, with very slim chance of ever starting up again.

This course of events and the final decision indicate a unique set of processes taking place in the Caspian energy field. It is very difficult to argue that the decision to choose TAP was not strategic and geo-political. The behind-the-scenes events occurring were largely connected to the beneficiaries of the project as well as to the strategic rapprochement of Russia and Azerbaijan. We suggest that the decision to terminate Nabucco was taken in Baku, and for which motivating factors are numerous. Firstly, the Nabucco pipeline was a joint EU venture, while Azerbaijan and Turkey have supported the TAP and the important midway junction TANAP. Secondly, the route is 500 kilometers shorter than the Nabucco-West and therefore more economically viable. Thirdly, the TAP infrastructure will primarily travel through Greece, eliminating the risk of interruptions in the supply chain. As a result of EU austerity measures in Greece, the country was forced to privatize the state-owned energy company DEPA and the state gas provider DESFA. Azerbaijani-owned SOCAR was the buyer of the Greek DESFA. The strategic implications of the decision for the TAP project are now clearer than ever. Fourthly, Azerbaijan did not want to sour its relationship with Russia. Fifthly, Azerbaijan and Turkey aimed to enhance their role as pivotal energy suppliers for the European markets (Weiss, 2013).

The Caspian Basin re-emerged as a source of global attention when a new race started for the access of its resources (Kleveman, 2003). It is referred to as the New Great Game by many academics, indicating the historical analogies between contemporary rivalries and the ones between imperial Russia and Britain in the 19th Century (Mandelbaum, 1998). Along with increased competition, the position of the newly independent Caspian littoral states—Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Turkmenistan—has dramatically shifted. Possessing influential power over their respective reserves, the three states must also compromise for access to energy transit routes, know-how, and capital with various external parties.

With regards to regional disputes, numerous implications exist. Firstly, the numerous ethnic and territorial disputes have an adverse impact on both the energy supply potential and the business environment in general. Recently rated as a dangerous conflict area, the situation in The Northern Caucasus region might unfold with devastating regional consequences (International Crisi Group, 2014). Moreover, the disputes over the legal status of The Basin endanger the stability of the area. Therefore the sui generis legal status offers the only viable approach available and needs to be capitalized on.

Finally, as identified earlier, The Caspian Basin has emerged as a key area of European interest with clear focus on the energy supply potential. However, The EU approach could be viewed as too fragmented. Often unable to speak with a common voice on energy related issues, The EU lags behind Russia in terms of increased cooperation initiatives. Even in the effort to try to diversify its energy supply by avoiding Russia and gaining access to the heart of the Caspian, The EU failed due to its over-inflated view of its influence in the region. Compounding this problem further is the fact that Caspian littoral states simultaneously strive for their own economic power and independence. They may not want to stumble from one strategic umbrella to another, but instead, to solidly stabilize a position for their own voice in the future of Caspian energy matters. When fighting for energy security, The EU will have to anticipate other emerging players in the New Great Game, and must remember that tapping into other energy reserves now, in contrast to the past, comes at a price.

An External Policy to Serve Europe’s Energy Interests. (2006). European Commission. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/energy_transport/international/doc/paper_solana_sg_energy_en.pdf, 2-3. [Accessed on 13 February 2015]

Aras, B. and Croissant, M.P. (1999). Oil and Geopolitics in the Caspian Sea Region Westport: Praeger Publishers.

Baker, B. and Rowley, M. (2009). The Nabucco Gas Pipeline Project. A Bridge to Europe? Pipeline and Gas Journal 236, No. 6 (Autumn 2009): 1-2. Retrieved from http://www.pipelineandgasjournal.com/nabucco-pipeline-project-gas-bridge-europe [Accessed on 5 March 2015]

Bajrektarevic, A.H. (2011). The Melting Poles: Between Challenges and Opportunities. Central European Journal of International and Security Studies, Vol. 5/1 (March 2011). Retrieved from http://static.cejiss.org/data/uploaded/13835989259862/1_0.pdf [Accessed on 22 April 2015]

Baran, Z. (2007). EU Energy Security: Time to End Russian Leverage. The Washington Quarterly 30, No. 4 (Autumn 2007): 133. Retrieved from http://muse.jhu.edu/login?auth=0&type=summary&url=/journals/washington_quarterly/v030/30.4baran.pdf [Accessed on 12 January 2015]

Boom and Gloom. (March 8, 2007). The Economist. Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/node/8819945 [Accessed on 19 December 2014]

BP Statistical Review of World Energy. (2013). British Petroleum. Retrieved from http://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/pdf/statistical-review/statistical_review_of_world_energy_2013.pdf, 8, 24. [Accessed on 25 November, 2014]

Brussels Okays Austrian Rules for Nabucco Construction. (February 11, 2008). Downstream Today. Retrieved from http://www.downstreamtoday.com/news/article.aspx?a_id=8624. [Accessed on 10 January, 2015]

Crandall, M.S. (2006). Energy, Economics, and Politics in the Caspian Region. Dreams and Realities. Westport: Praeger Publishers.

Dekmejian, R.H. and H.H. Simonian. (2003). Troubled Waters: The Geopolitics of The Caspian Region. New York: I.B. Tauris.

Del Sole, C. (2013). Azerbaijan Chooses TAP over Nabucco to Provide Gas Pipeline to Europe. The European Institute. Retrieved from http://www.europeaninstitute.org/beta/index.php/ei-blog/181-august-2013/1771-azerbaijan-chooses-tap-over-nabucco-to-provide-gas-pipeline-to-europe-88 [Accessed on 15 December, 2014]

Dettoni, J. (October 1, 2014). Russia and Iran Lock NATO Out of Caspian Sea. The Diplomat. Retrieved from http://thediplomat.com/2014/10/russia-and-iran-lock-nato-out-of-caspian-sea/. [Accessed on 17 January, 2015]

Goldwin, D.L. and J.K. Kalicki. (2005). Energy and Security: Toward a New Foreign Policy Strategy. Washington DC, Woodrow Wilson Center Press.

Human Rights on the Line: The Baku- Tbilisi- Ceyhan Pipeline Project. (2003) Amnesty International. Retrieved from http://bankwatch.org/documents/report_btc_hrights_amnesty_05_03.pdf, 14 [Accessed 20 November, 2014]

INOGATE Oil and Gas Directory 2003-2004. (2004). Azerbaijan: Overview of Oil & Gas Sector. Interstate Oil and Gas Transport to Europe. Retrieved from http://www2.inogate.org/html/resource/azerbaijan.pdf, 20. [Accessed on 10 February 2015]

Janis, M.W. (2003). An Introduction to International Law, 4th ed. New York: Aspen Publishers.

Kapila, S. (November 6, 2014). Iran-India Strategic Partnership needs Resuscitation-Analysis. Eurasia Review. Retrieved from http://www.eurasiareview.com/06112014-iran-india-strategic-partnership-needs-resuscitation-analysis/. [Accessed on 12 December, 2014]

Kazakhstan Overview. (2003). U.S. Energy Information Administration. Retrieved from http://www.eia.gov/countries/cab.cfm?fips=kz. [Accessed on 19 December 2014]

Kleveman, L. C. (2003). The New Great Game: Blood and Oil in Central Asia. New York: Grove Press.

Kubicek, P. (2013). Energy Politics and Geopolitical Competition in the Caspian Basin. Journal of Eurasian Studies 4, No. 2. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1879366513000171!!!!!?np=y. [Accessed on 22 February 2015]

Mandelbaum, M. (March 28, 1998). The Great Game Then and Now«, Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved from http://www.cfr.org/oil/great-game-then-now-address-conference-oil-gas-caspian-sea-region-geopolitical-regional-security-sponsored-friedrich-ebert-foundation/p179 [Accessed on 9 February, 2015]

Marketos, T.N. (2009). Eastern Caspian Sea Energy Geopolitics: A Litmus Test for the US-Russia-China Struggle for the Geostrategic Control of Eurasia. Caucasian Review of International Affairs 3, No. 1 (Winter 2009): 4. Retrieved from http://www.cria-online.org/6_2.html [Accessed on 5 January 2015]

Mehdiyoun, K. (2000). Ownership of Oil and Gas Resources in the Caspian Sea. American Journal of International Law 94, no. 1 (January 2000), 2. Retrieved from https://litigation-essentials.lexisnexis.com/webcd/app?action=DocumentDisplay&crawlid=1&doctype=cite&docid=94+A.J.I.L.+179&srctype=smi&srcid=3B15&key=038c979c7f74b1ee5e8b631b43fae069 [Accessed on 10 February 2015]

Mihalache, A.E. (January 12, 2015). South Stream is Dead. Long Live South Stream. Energy Post. Retrieved from http://www.energypost.eu/south-stream-dead-long-live-south-stream/ [Accessed on 15 January, 2105]

North Caucasus. (2014). International Crisis Group. Retrieved from http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/regions/europe/north-caucasus.aspx. [Accessed 8 January, 2015]

Oleson, T. (October 20, 2013). Gaming the System in the Caspian Sea: Can Game Theory Solve a Decades-Old Dispute? EARTH Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.earthmagazine.org/article/gaming-system-caspian-sea-can-game-theory-solve-decades-old-dispute. [Accessed on 26 November 2014]

Pannier, B. (November 19, 2010). Caspian Summit Fails to Clarify Status, Resource Issues. Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty. Retrieved from http://www.rferl.org/content/Caspian_Summit_Fails_To_Clarify_Status_Resource_Issues/2225159.html. [Accessed on 20 November, 2014]

Raczka, W. (2000). A Sea or a Lake? The Caspian’s Long Odyssey. Central Asian Survey 19, No. 2 (2000): 201-202. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/713656182#.VQLKMuGHi4Y. [Accessed on 5 February 2015]

Remaking Nabucco. (18 February, 2012). Natural Gas Europe. Retrieved from http://www.naturalgaseurope.com/a-smaller-nabucco [Accessed on 21 November, 2014]

The Abominable Gas Man. (October 14, 2010). The Economist. Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/node/17260657. [Accessed on 20 November, 2014]

The South Stream Offshore Pipeline project. (2014). South Stream Project. Retrieved from http://www.south-stream-offshore.com/project/ [Accessed on 10 January, 2015]

Tiezzi, S. (May 9, 2014). China’s ‘New Silk Road’ Vision Revealed. The Diplomat. Retrieved from http://thediplomat.com/2014/05/chinas-new-silk-road-vision-revealed/. [Accessed on 8 January 2015]

Turkmenistan Opens New Iran Gas Pipeline. (January 6, 2010). BBC. Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/8443787.stm. [Accessed on 7 January 2015]

Turkmenistan Background. (2012). U.S. Energy Information Administration. Retrieved from http://www.eia.gov/countries/cab.cfm?fips=TX. [Accessed on 19 December 2014]

U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service. (2006). Caspian Oil and Gas: Production and Prospects, by Bernard A. Gelb, CRS Report RS21190.Washington DC: Office of Congressional Information and Publishing

Weiss, C. (July 13, 2013). European Union’s Nabucco Pipeline Project Aborted. World Socialist Web Site. Retrieved from http://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2013/07/13/nabu-j13.html [Accessed on 13 December, 2105]

Zeinolabedin Y, M.S. Yahyaour and Z. Shirzad. (2009) . Geopolitics and Environmental Issues in the Caspian Sea. Caspian Journal of Environmental Sciences 7, no. 2 (2009): 116. Retrieved from http://research.guilan.ac.ir/cjes/.papers/1447.pdf [Accessed on 13 February 2015]

Zimnitskaya, H. and J. von Geldern. (2010). Is the Caspian a Sea; and Why does it Matter? Journal of Eurasian Studies 2, no. 1 (2010): 10. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1879366510000424 [Accessed on 12 February 2015)

Figure 1: The proposed and already effective division of the Caspian basin

Figure 2: The planned South Stream and Nabucco gas pipelines

Table 1 : Proven Caspian Oil Reserves (In billion barrels)

Table 2 : Proven Caspian Natural Gas Reserves (In Trillion Cubic Meters)

Last Update: 24/12/2021