An earthquake measuring 7.7 on the Richter scale in Myanmar on March 28 2025 without a doubt is a serious one. But the willingness of Myanmar generals to truly seek international assistance has to be contextualized too.

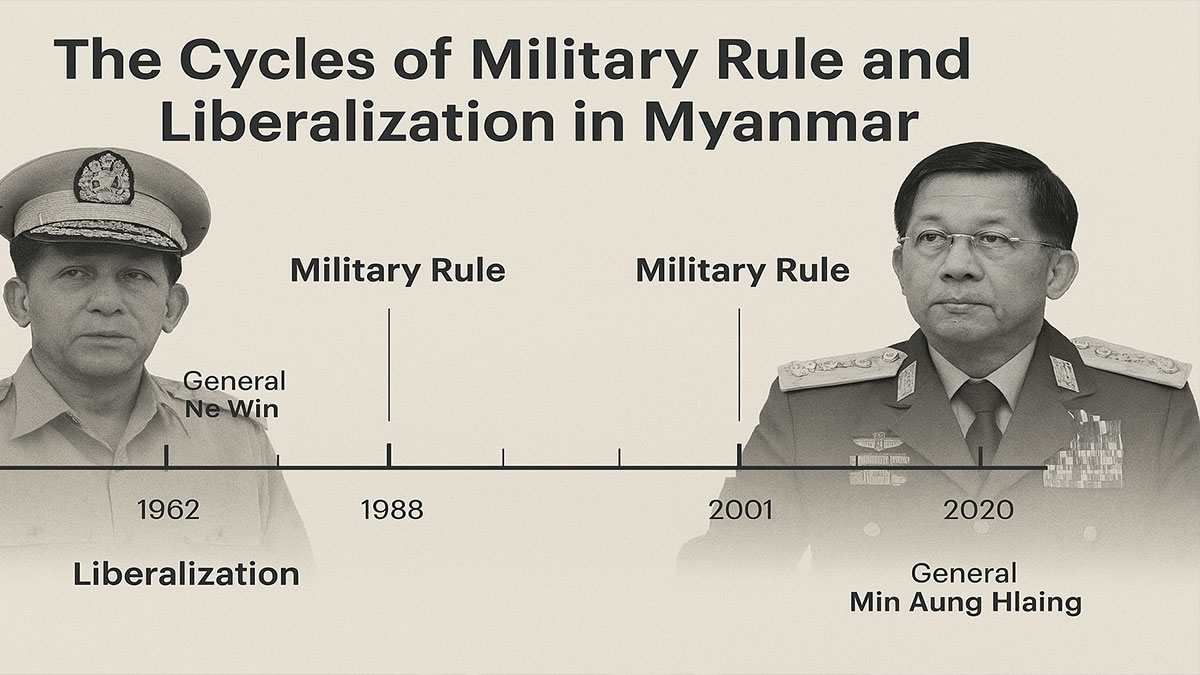

Myanmar’s modern political history is a story of military dominance, brief liberalization, and recurring authoritarianism. Since General Ne Win’s 1962 coup, the country has seen intermittent reforms, only to be pulled back into military control.

The most notable liberalization period occurred under President Thein Sein (2011–2016), a former general who initiated political and economic reforms. However, these efforts were reversed under Senior General Min Aung Hlaing’s coup in 2021.

Invariably, Myanmar’s political trajectory from General Ne Win’s isolationist socialism to Than Shwe’s hardline military rule, Thein Sein’s cautious reforms, and the military’s resurgence under Min Aung Hlaing, all dictate the dynamics of how much aid can go into this hermetic yet war torn country.

On March 2, 1962, General Ne Win staged a coup, for example, overthrowing the civilian government led by Prime Minister U Nu. Under the guise of protecting national unity, Ne Win established a military-led socialist state under the Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP).

The so-called “Burmese Way to Socialism” introduced an autarkic economic policy that isolated Myanmar from global trade, leading to widespread poverty, economic stagnation, and diplomatic isolation.

Key policies under Ne Win’s rule included the nationalization of industries. For the lack of better word, the state took control of all major businesses, crippling private enterprise and reducing economic efficiency.

Aside the from above, General Ne Win also introduced a strict one-party rule. Political opposition was banned, and dissent was brutally suppressed. Meanwhile, xenophobia and expulsions in Myanmar became all the rage: Ne Win expelled Indian and Chinese business communities, dismantling the country's merchant class.

Ne Win’s policies led to economic collapse, culminating in mass protests in 1988, known as the 8888 Uprising (August 8, 1988). The military responded with brutal crackdowns, killing thousands of protesters. Facing mounting instability, Ne Win resigned but ensured that power remained with the military, paving the way for General Than Shwe’s rise.

After Ne Win’s resignation, a new military junta, the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), took control in 1988, later rebranded as the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) in 1997. Under General Than Shwe in 1992-2021, Myanmar remained one of the most repressive regimes in the world.

Than Shwe ruled with an iron fist, ignoring international condemnation of his human rights abuses. Key events of his tenure included the 1990 Elections. Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) won a landslide victory, but the military refused to cede power.

Continued suppression of dissent also gained in crescendo. Political opponents, including Suu Kyi, remained under house arrest. Meanwhile, during this reign of General Than Shwe, economic mismanagement and corruption reigned supreme. Evidently, the military elites enriched themselves while the economy stagnated.

At any rate, General Than Shwe drafted a constitution designed to cement military dominance, reserving 25% of parliamentary seats for the army and granting it emergency powers.

Despite his authoritarian rule, Than Shwe recognized that Myanmar needed some level of engagement with the global economy to survive.

In 2010, he unexpectedly initiated a transition to semi-civilian rule, paving the way for Thein Sein’s presidency in 2011. However, this transition was carefully controlled to ensure that the military retained ultimate power.

Former General Thein Sein took office in 2011 as Myanmar’s first civilian president under the military-drafted 2008 Constitution. His tenure marked the most significant period of political and economic liberalization Myanmar had seen in decades.

Thein Sein’s key reforms included:

1. Political Opening: He released thousands of political prisoners, including Aung San Suu Kyi, and allowed the NLD to participate in elections.

2. Economic Reforms: Myanmar moved away from a military-controlled economy, allowing foreign investment and lifting restrictions on private businesses.

3. Diplomatic Engagement: Thein Sein’s government reestablished relations with Western countries, leading to the lifting of U.S. and EU sanctions.

4. Media Freedoms: Press restrictions were eased, allowing greater freedom of expression.

These reforms led to Myanmar’s reintegration into the global community, and in 2015, the NLD won a landslide victory in the general elections. The military, however, remained wary of full democratization.

Despite Thein Sein’s reforms, Myanmar’s military continued to exert influence over the government. On February 1st 2021, General Min Aung Hlaing led a coup, overthrowing the civilian government just as the NLD was set to begin its second term. The military justified the coup by alleging election fraud, but the real motive was to maintain military dominance.

Key developments under Min Aung Hlaing’s rule included brutal crackdowns on protesters. The coup sparked nationwide protests, which were met with extreme violence. Thousands of civilians were killed, imprisoned, or tortured.

Economic collapse also became an endemic nature. Indeed, foreign investment fled the country, and Myanmar’s economy nosedived due to sanctions and instability.

Invariably, diplomatic isolation from ASEAN and the international community was self induced by Senior General Myint Aung Hlang. Just as ASEAN and the international community condemned the coup, with even China showing signs of unease, none of these displeasure caused Senior General Myint Aung Hlang to budge.

More importantly, ethnic conflicts also took a spike. Armed resistance groups, including the Karen National Union and Kachin Independence Army, intensified their battles against the junta.

As things stand, the 2025 earthquake in Myanmar further exposed the military regime’s incompetence. Unlike Thein Sein’s government, which sought international aid after Cyclone Nargis (2008), Min Aung Hlaing’s junta refused to allow humanitarian organizations full access to affected areas although he has asked for international help.

This decision will exacerbate the humanitarian crisis, as thousands will not be left without aid. But with soldiers will probably get the lion's share of what ever aid that trickles in.

Be that as it may, Myanmar’s military rulers have been reluctant to accept external help during natural disasters, fearing that foreign involvement could weaken their grip on power.

In contrast, ASEAN countries like Indonesia and Thailand have been more open to international aid during crises. This stark difference in disaster response underscores how Myanmar’s junta prioritizes its own survival over the well-being of its people.

Myanmar’s political trajectory remains trapped in a cycle where brief periods of liberalization are inevitably reversed by the military. Thein Sein’s reforms raised hopes for democratic transition, but the military’s entrenched power structure ultimately reasserted itself under Min Aung Hlaing.

The 2025 earthquake demonstrated the junta’s continued prioritization of control over humanitarian needs. One can only see the military or Tatmadaw in local parlance will change their cruel postures.

For Myanmar to break free from this cycle, structural changes must occur within both its military and civilian institutions. Until then, the country remains a case study of how military elites can manipulate liberalization efforts to maintain long-term dominance.

Last Update: 06/04/2025