AEI-Insights - AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ASIA-EUROPE RELATIONS

(ISSN: 2289-800X); JANUARY, 2015; Volume 1, Number 1

Ansgar H. Belkea and Ulrich Volzb

aUniversity of Duisburg-Essen & IZA Bonn

University of Duisburg-Essen,

Faculty of Economics and Business Administration,

Universitätsstraße 12, 45117 Essen,

Germany

Tel: +49 201 183 2277

E-mail: ansgar.belke@uni-due.de

bSOAS, University of London & German Development Institute

SOAS, University of London,

Department of Economics, Thornhaugh Street,

Russell Square, London WC1H 0XG,

United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0)207 898 4721

E-mail: uv1@soas.ac.uk

The exchange rate can have important effects on inflation, export performance and growth. Against the backdrop of a strong euro and calls for the European Central Bank (ECB) to lower the common currency’s external value, this article discusses the challenges for the ECB and the Eurozone stemming from a strong euro and weights the arguments for and against currency intervention by the ECB to weaken the euro. We argue that a devaluation strategy is no panacea to the Eurozone’s problems. Macroeconomic imbalances within the Eurozone need to be resolved primarily by structural adjustments. However, a modest euro devaluation and higher inflation in the core countries will facilitate adjustments in the periphery countries. Given that a resolution of the European debt problems and a sustained recovery of the Eurozone is also in the interest of the rest of the world, a modest euro devaluation should not trigger a competitive devaluation spiral.

Euro Exchange rate; European Central Bank; Monetary Policy; Foreign Exchange Intervention, Currency Wars.

Note: Paper prepared for the inaugural issue of AEI Insights. Parts of the paper draw liberally from a briefing paper written by the first author for the European Parliament’s Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs in June 2014 (Belke, 2014).

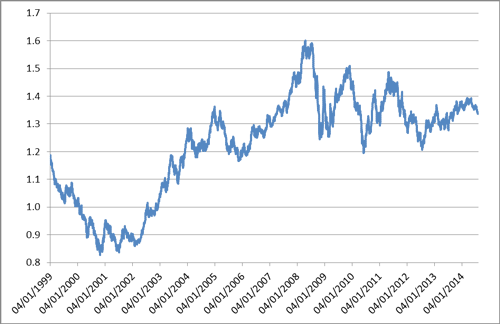

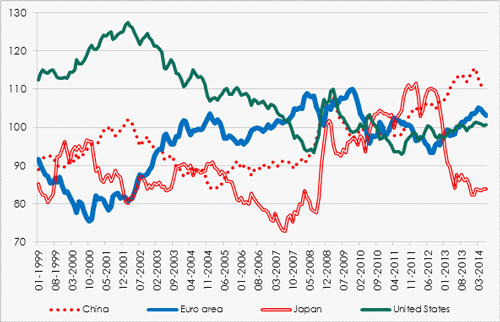

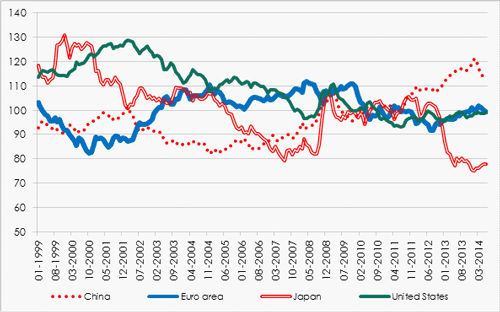

The euro-dollar exchange rate has seen large fluctuations over the past decades (Figure 1). After its creation on 1 January 1999, the euro (EUR) depreciated against the US dollar (USD) from its initial value of 1.9 USD/EUR to 0.83 USD/EUR in October 2001. It then rose to an all-time high of 1.6 USD/EUR in April 2008. Between July and October 2008, with the outbreak of the Global Financial Crisis, the euro dropped by 22°%. By October 2009, it had risen again to 1.5 USD/EUR due to its ‘safe haven’ status. With the outbreak of the European debt crisis and speculation on a break-up of the euro area, the euro slumped again below 1.2 USD/EUR by June 2010. After regaining its losses and rising to 1.49 USD/EUR in May 2011, the euro short selling started again so that the euro fell to 1.21 USD/EUR in July 2012. It was only after European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi uttered the now famous words “[w]ithin our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough”(Draghi, 2012) on 26 July 2012 that the euro regained trust and started rising again. By end-2013, the euro had reached a level of almost 1.4 USD/EUR again. The euro has not only appreciated against the dollar, but also in trade-weighted terms (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1: USD/EUR, January 1999-August 2014

Source: Compiled by authors with data from the ECB.

Figure 2: BIS nominal effective exchange rates (monthly averages; 2010=100), January 1999-June 2014

Source: Compiled by authors with data from the BIS effective exchange rate indices (updated 15 July 2014), www.bis.org/statistics/eer/

Figure 3: BIS real effective exchange rates (monthly averages; 2010=100), January 1999–June 2014

Source: Compiled by authors with data from the BIS effective exchange rate indices (updated 15 July 2014), www.bis.org/statistics/eer/

While Draghi’s verbal intervention has been very successful in restoring trust in the euro’s survival and thereby ended speculation against the euro, the renewed strength of the euro has complicated the resolution of Europe’s sovereign debt and growth problems. It is hence no coincidence that the ECB has received numerous calls for intervening in the foreign exchange markets and drive down the euro’s external value. Draghi, like his predecessors, has repeatedly emphasised that the ECB takes into account the level of the euro’s exchange rate only to the extent that it affects the ECB achieving its inflation target of below but close to 2°%. During a press conference in Brussels on 8 May 2014 Draghi (2014b) stated:

“...over the last few days we received plenty of advice from political figures, from institutions and, almost every day now, on interest rates, on exchange rates but also, on the other side of the scale, on the excess liquidity. So we are certainly thankful for this advice and certainly respect the views of all these people. But we are, by the Treaty, we are independent. So people should be aware that if this might be seen as a threat to our independence, it could cause long-term damage to our credibility.”

Nonetheless, Draghi and other members of the ECB’s Executive Board have conceded that “[t]here is no doubt that the appreciation of the euro since the summer of 2012 has contributed to the current low level of inflation” (Coeuré, 2014) and that “the strengthening of the exchange rate in the context of low inflation is cause for serious concern in the view of the Governing Council” (Draghi, 2014b). ECB Governing Council member Josef Bonnici warned that “[i]f the exchange rate keeps behaving as it is, if it gets stronger, then it becomes an issue that one has to take into account” (Buell & Lawton, 2014).

When the ECB adopted forward guidance in July 2013,1 the expectation was that this would put downward pressure on the euro exchange rate. As Draghi (2014a) points out “the ECB’s forward guidance ... creates a de facto loosening of policy stance, and real interest rates are set to fall over the projection horizon. At the same time, the real interest rate spread between the euro area and the rest of the world will probably fall, thus putting downward pressure on the exchange rate, everything else being equal.” Against the expectations, the euro, however, continued to strengthen. This is in part due to capital inflows to the euro area reflecting improved fundamentals of the euro area including a growing current account surplus and more benign investor sentiments.

To the extent that “[t]he strengthening of the effective euro exchange over the past one and a half years has certainly had a significant impact on our low rate of inflation, and, given current levels of inflation”, Draghi (2014a) has pointed out that the exchange rate is “becoming increasingly relevant in [the ECB’s] assessment of price stability.”The exchange rate can also have important effects on export performance and thereby growth. Against this background, this article discusses the challenges for the ECB and the Eurozone stemming from a strong euro and weights the arguments for and against currency intervention by the ECB to weaken the euro and possible implications of such a policy for other economies. The next section discusses the challenges arising from a strong euro for the euro area and the ECB’s monetary policy. Section 3 discusses the potential pitfalls of exchange rate intervention. Section 4 concludes.

There are three channels through which a too-strong euro can harm the Eurozone’s economy. Firstly, an appreciation of the currency lowers the price of imports and puts downward pressure on the inflation rate, which is already too low in the Eurozone. Second, a too-strong exchange rate can hurt exports from the Eurozone and dampen much-needed growth, especially in the Eurozone’s periphery countries which are still struggling to regain competitiveness. Thirdly, through the inflation and growth effects, too strong a euro can hamper the reduction of debt across the Eurozone.

Effects on inflation and challenges for the ECB’s monetary policy

As pointed out by Belke (2014, p.7),”[t]he challenges posed by the strength of the euro for ECB’s monetary policy are to be assessed in a macroeconomic context characterised by overall low inflation levels—stemming from necessary competitive price adjustments in the euro-area periphery as well as a from widespread deleveraging processes still on-going—and improved growth projections in the euro-area.”

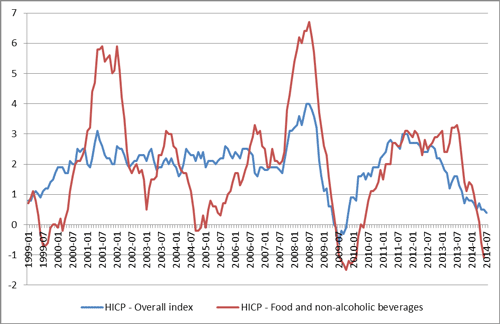

Since February 2013, Eurozone inflation has been constantly below 2°% and moving ever closer to zero (Figure 4). Inflation rates for food and non-alcoholic beverages have already entered negative territory. Three factors are of particular importance. First, a general fall in global commodity and oil prices has driven down inflation across all advanced economies. According to Draghi (2014d), “it was mostly the declines in the price of oil and food and perhaps some other commodities [since late 2011] that have accounted for something like 75%–80% of the difference between inflation then and inflation now [June 2014].”

Figure 4: Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) for the euro area (changing composition)–Overall HICP index and HICP for food and non-alcoholic beverages (annual rate of change)

Source: Compiled by authors with data from the ECB/Eurostat.

The two other factors are specific to the Eurozone (Draghi, 2014c). One is the necessary downward adjustment of prices and wages in the Eurozone’s crisis economies which drags down aggregate inflation.2 As Draghi (2014c) puts it:

“Several euro area countries are currently undergoing internal devaluation to regain price competitiveness, both internationally and within the currency union. The crucial adjustments vis-à-vis other euro area countries have to take place irrespective of changes in the external value of the euro. This process began hesitantly in the early years of the crisis, largely due to nominal rigidities in wages and prices. The result was that adjustment took place more through quantities – i.e. unemployment – than through prices. Stressed countries thus experienced a protracted period of declining disposable incomes and long-drawn-out price adjustment. In this context, several have seen domestic core inflation – that is, excluding the energy and food price effects ... – fall well below the euro area average. For example, the recent overall fall in services price inflation for the euro area is almost entirely accounted for by price declines in these components in stressed countries. Nevertheless, in the last few years relative price adjustment has accelerated in stressed countries. While this may also have initially weighed on disposable incomes, by creating a closer alignment between relative wage and productivity developments, it should increasingly support future incomes through the competitiveness channel. Export growth has been impressive in several stressed countries. And indeed, nominal income growth in stressed countries turned positive in the fourth quarter of 2013.”

The third factor, which is a “common factor” for all Eurozone countries, is the appreciation of the euro exchange rate since July 2012. While internationally traded commodity prices haven’t moved much in dollar terms over this period, the euro’s appreciation has driven down import prices which has fed into falling inflation. Draghi (2014c) emphasises the importance of the exchange rate effect for a relatively open economy like the Eurozone, especially in conjunction with falling global food and energy prices:

“The bulk of the imported downside pressures on euro area consumer prices are explained by the strengthening of the effective euro exchange rate, in particular vis-à-vis the dollar. In the past year or so, oil prices in US dollars have fluctuated – by historical standards – over a relatively narrow range. And they have exhibited no clear downward or upward trend. This creates a balance of forces that might affect future inflation. On the one hand, lower commodity prices driven by euro appreciation help compensate for the generally weak developments in disposable income in the euro area. Indeed, real disposable income declined at a slower pace throughout 2013, and turned slightly positive in the fourth quarter, increasing by 0.6% year-on-year. To the extent that this supports domestic demand in the euro area it will also create upward pressure on inflation. On the other hand, exchange rate appreciation affects external demand and reduces the competitiveness gains of price and cost adjustment in some euro area countries. This has a countervailing effect on real disposable incomes, while also making disinflation more broad-based. Indeed, if we look at prices of non-energy industrial goods, which are mainly tradable, we see a downward trend across all euro area countries.”

Given the ECB’s worries about deflationary effects of a rising euro, and hence the undershooting of the ECB’s inflation target of below but close to two percent, it is not surprising that the ECB has apparently intensified verbal interventions aiming at lowering the external value of the euro since spring 2014. In May 2014, Draghi (2014b) voiced that “the strengthening of the exchange rate in the context of low inflation is cause for serious concern in the view of the Governing Council”. At the August 2014 meeting of the Governing Council, Draghi (2014f) gave the clearest hint to date that he would like to see a euro devaluation when saying that “the fundamentals for a weaker exchange rate are today much better than they were two or three months ago.”

Effects on growth

While reiterating that “[t]he exchange rate is not a policy target for the ECB”, Draghi (2014e) admitted his concerns in a hearing at the European Parliament in Strasbourg in July 2014 that “[i]n the present context, an appreciated exchange rate is a risk to the sustainability of the [Eurozone’s] recovery”. While the effects of exchange rate appreciation on growth are not straightforward and depend on the structural characteristics of an economy and export and import price elasticities in particular, the general understanding is that exchange rate appreciation will hamper exports and drag down growth. While Imbs and Méjea (2010) find low export elasticities for rich open economies, Bénassy-Quéré et al. (2014, p.7) estimate that for France, the Eurozone’s second largest economy, “a 10°% depreciation in the euro in relation to a partner country outside the eurozone increases the value of the average exporter’s sales to this country by around 5-6°%”, with most of this effect realised in the same year as the depreciation. Moreover, they estimate that a “10°% appreciation in the euro has a symmetrical impact, with the value of exports reduced by an average of 5-6°% for an exporting company” (ibid.). The aggregate effect of a 10°% euro depreciation may be even larger with 7-8°% because new firms may start to export. Overall, Bénassy-Quéré et al. (2014, p.7) estimate that “a 10°% depreciation in the euro would result in a 0.6°% increase in the French GDP after one year and a 1°% increase after two years.”Belke (2014, p.14), in contrast, is more sceptical and points out that “the relation between the long-run interest rate, the exchange rate and in turn, growth, is rather loose”.

Effects on debt

By contributing to low inflation (or even deflation) and lower growth rates in the Eurozone, a strong exchange rate can make the reduction of public and private debt overhang more painful and lengthy. Given that most debt is fixed in nominal terms, their real value gets eroded by higher inflation.3 To overcome the debt overhang and invigorate growth in both the US and Europe, Chinn and Frieden (2011, p.6) advocate to “use a tried-and-true tool to manage crippling systemic debt: inflation.” The argument for reflating the economy to fight a debt overhang was originally put forward by Bernanke (2003) in a speech in Tokyo in 2003:

“I think the [Bank of Japan] should consider a policy of reflation before re-stabilizing at a low inflation rate primarily because of the economic benefits of such a policy. One benefit of reflation would be to ease some of the intense pressure on debtors and on the financial system more generally. Since the early 1990s, borrowers in Japan have repeatedly found themselves squeezed by disinflation or deflation, which has required them to pay their debts in yen of greater value than they had expected. Borrower distress has affected the functioning of the whole economy, for example by weakening the banking system and depressing investment spending. Of course, declining asset values and the structural problems of Japanese firms have contributed greatly to debtors’ problems as well, but reflation would, nevertheless, provide some relief. A period of reflation would also likely provide a boost to profits and help to break the deflationary psychology among the public, which would be positive factors for asset prices as well. Reflation—that is, a period of inflation above the long-run preferred rate in order to restore the earlier price level--proved highly beneficial following the deflations of the 1930s in both Japan and the United States.”

In a similar vein, Chinn and Frieden (2011, p.6) argue that “as prices rise and wages follow, debtors (house-holds, businesses and governments) find it easier to service their debts and can more readily resume regular economic behavior.” Chinn and Frieden (2011, p.7) acknowledge that inflation would hurt creditors, but they maintain that, “as politically daunting as that might be, some redistribution from creditors to debtors would almost certainly be part of any durable settlement of the Eurozone debt crisis anyway, as it has been in the case of the Greek sovereign debt restructuring.” Likewise, Rogoff (2011) argues that “[i]f direct approaches to debt reduction are ruled out by political obstacles, there is still the option of trying to achieve some modest deleveraging through moderate inflation of, say, 4 to 6 per cent for several years. Any inflation above 2 per cent may seem anathema to those who still remember the anti-inflation wars of the 1970s and 1980s, but a once-in-75-year crisis calls for outside-the-box measures.”

Importantly, Chinn and Frieden (2011, p.11), argue that a slightly higher inflation rate in the Eurozone’s core countries would facilitate adjustment in the periphery:

“Consider the adjustment of labor markets to chronic unemployment. It is widely agreed that in order to create jobs, Spain and other relatively unproductive economies on the southern periphery of the Euro-zone need to reduce real wages. But it is very difficult to impose nominal wage cuts, especially in countries with strong organized labor. By contrast, a bit of inflation could erode real wages, without the perception that labor is being singled out to bear the adjustment burden. We’re not claiming that inflation is a painless way to speed deleveraging. We are claiming, though, that it is less painful than the realistic alternatives. At this juncture, the highest priority for monetary policy in the United States (and, for that matter, in Europe)ought to be getting the economy out of the long, deep recession that has cost trillions of dollars in lost output and disrupted tens of millions of lives. Unusual times call for unusual measures.”

But there are, of course, also critics who maintain that “[t]he idea that inflation can be raised by a controlled amount for a fixed period then easily brought back down again is naive” (Redwood and Bootle as quoted by Buttonwood, 2011).

Having discussed potential negative side effects of a strong euro exchange rate that may justify further verbal intervention or even intervention in the foreign exchange markets, we now turn to potential drawbacks of such action.

What is the equilibrium level for the exchange rate?

Our starting point is the fundamental insight that the variable driving expenditure switching is not the nominal but the real exchange rate and that there is scarce evidence that central banks are able to affect the real exchange rate durably (Belke, 2014). As pointed out by Belke (2014, p.8-9),the statement “the euro is too strong” necessitates an exact well-founded benchmark, an estimate of the equilibrium exchange rate which corresponds with the ECB’s HICP inflation target. But one can hardly think of a more controversial issue in international macroeconomics than identifying equilibrium exchange rates (Krugman et al., 2012, p.350ff.).

Which factors are driving the euro appreciation? Some analysts try to determine the drivers of the euro’s appreciation by referring to the ECB balance sheets which have been shrinking vis-à-vis the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) and the Bank of England’s(BoE) balance sheet during the previous year. The significant current account surplus of the euro area as a whole, capital inflows into the euro area’s South, at times falling yields for dollar bonds and shrinking amounts of dollar traded euro-area monetary financial institutions may also have had an impact (Belke, 2014).

Currently, the euro appears too strong for some of the Southern euro-area countries and too weak for a set of Northern euro-area countries, among them Germany. If this can be corroborated, a further fall of the external value of the euro would create windfall gains for countries which are already now faring better in macroeconomic terms (Belke, 2014).

In this context, it is important to assess the extent to which the euro is too strong for a specific euro area member country. For this purpose, for instance Redeker (based on a simple unit labour cost calculus, see Eckert and Zschaepitz, 2014)estimates the USD/EUR exchange rate pain thresholds and ranks the euro area member countries accordingly. The USD/EUR threshold is estimated to be 1.54 for Germany, 1.29 for Spain, 1.28 for Finland, 1.23 for France, 1.19 for Italy, and a very low 1.04 for Greece. The point estimate for Germany turns out to be rather close to the pain threshold of USD/EUR 1.55 which has been calculated by Belke et al. (2013). Accordingly, these studies come up with the conclusion that there is no unique USD/EUR exchange rate to target which is able to “revive the euro-area economy, avoid deflation and preserve the ECB price stability target” (Belke, 2014).

Moreover, the economic literature has often detected destabilising effects from intervention. As highlighted by Belke et al. (2004): “Experience shows that intervention increases the probability of stability only when the rate is clearly misaligned. An additional, and perhaps more striking argument against intervention, is that the factors driving the direction and intensity of exchange rate moves— that is, for instance, expected growth and capital returns—are beyond the reach of monetary policy: apart from the price level it is hard to see how monetary policy can have a systematic impact on the variables which are usually held responsible for exchange rate levels”.

Additionally, the standard economic relation among the exchange rate and its fundamental drivers itself conveys the impression to be highly distorted by unconventional monetary policies undertaken by the world’s leading central banks. Hence, it is not at all surprising that the interest rate parity hypothesis does not have much explanatory value for the relatively high external value of the euro in the current macroeconomic scenario of low growth (Belke, 2014).

Finally, reiterated interventions are required to influence the exchange rate durably. However, direct foreign exchange interventions are politically costly. There is thus an incentive for central banks not to intervene in the foreign exchange market. However, the capital markets seem to have understood that the ECB’s unconventional monetary policies are targeted towards the exchange rate (Belke & Gros, 2014). In line with many others, Jolly et al. (2014) observe that “the biggest problem the E.C.B. really faces is the strength of the euro. The Federal Reserve, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan (BOJ) all set out deliberately to weaken their national currencies … and now the European Central Bank is catching up”.

ECB President Draghi has stressed on several occasions that the external value of the euro can definitely not be considered to represent an ECB policy target. When asked to comment whether the ECB “Governing Council has some kind of a trigger point where the euro exchange rate is too strong, prompting the bank to act in the future” he clearly responded “No, we don’t have a trigger. We just see that this is having the effect of basically depressing further the inflation rate. [....] And it’s actually the exchange rate that keeps the inflation rate low and depressed” (Draghi, 2014a).

It can be doubted that employing direct or indirect exchange rate policies to tackle bad growth performance in parts of the Eurozone will provide remedy. High (youth) unemployment and low GDP growth in some euro area member countries are structural phenomena. Besides significant fine-tuning problems, aplethora of studies has demonstrated that a too strong focus has been put on public budget and debt consolidation as compared to increasing international competitiveness of crisis countries (Belke, 2014, p.9-10;Gros et al., 2014). The biggest benefits of a weaker euro would relate to enhancing the euro area’s problem countries’ international competitiveness. If these benefits are later neutralised by higher wage growth, weakening the euro today does not appear to be a solution. If a spiral of devaluations and wage increases sets in, the ensuing unanticipated variability of uncertainty about the (equilibrium) euro exchange rate will have negative economic consequences. This type of macroeconomic environment often coincides “with periods of excessive speculation which have the potential to harm the economy because the speculation waves hamper a sound calculation by the export oriented firms” (Belke et al., 2004).

Taking this as a starting point, exchange rate policies backed by discretionary unconventional monetary policies could potentially trigger cumulative destabilising real effects and modify the dynamics of the economy permanently. It has to be added that most of the familiar standard asset price models for sovereign bonds or stocks cannot be used anymore since they do not properly incorporate the dynamic consequences of discretionary central bank interventions. Hence, it seems obvious that the recent appreciation of the euro was significantly driven by speculation about future ECB policy itself. Investors may be willing to test the bottom line of the ECB’s pain threshold for the USD/EUR exchange rate: is it located at 1.30, 1.40 or 1.50 (Belke, 2014; Belke et al., 2004). Overall the best way to calm down currency markets and stop the euro’s upward trend may be for the ECB to refrain from directly or indirectly targeting the exchange rate through its current and future unconventional monetary policy measures (Belke, 2014).

Belke (2014, p.10) maintains that a credible ignorance of the exchange rate level will put both entrepreneurs and politicians under pressure to undertake the necessary structural adjustments instead of hoping for central bank intervention. Moreover, he argues that”[e]specially in the case of negative supply shocks, one should refrain from accommodating devaluations which at best alleviate the short term symptoms of low growth in Europe. Proactive devaluations significantly lower the incentives to break open encrusted structures on labour and product markets and, thus, prospects for growth and employment” (Belke, 2014, p.10).

In the past it has nevertheless often been argued that low international competitiveness due to labour and product market sclerosis connected with low productivity can be counteracted much easier and quicker if the necessary macroeconomic adjustment is triggered through the exchange rate than if it would be conducted via wage cuts. The devaluation of the euro may thus work as a substitute for wage restraint and structural reforms (Belke et al., 2004, Belke et al., 2006). But the empirical evidence on this is mixed at best. For example, the positive employment effects that were claimed as a result of the UK’s and Italy’s exit of the European Monetary System (EMS) in 1992 should be ascribed to the policy reforms that were implemented in these countries at the time rather than the one-off devaluations of the British pound and the Italian lira after their exit from the EMS (Belke et al., 2004).Belke et al. (2004) therefore argue that:

“Hence, in empirical studies investigating the efficiency of exchange rate movements in terms of employment, the extent of reform has to be modelled as an explaining variable which is endogenous with regard to the choice of the exchange rate system. Then it will immediately become clear that structural reforms and not, as often maintained, proactive devaluations of the respective home currency are the most efficient way towards more growth and employment. Hence, the euro exchange rate cannot be regarded as an important short-term oriented instrument to pre vent path-dependence in unemployment in the presence of negative shocks.”

But the political pressures to weaken the euro are mounting currently. Above all, the French government is pushing for weakening the euro as the French economy is steadily losing competitiveness and the growth performance of the country is remaining rather poor. Dumping the external value of the home currency has been a policy tool frequently used already in the past to escape more painful structural reforms (Belke, 2014, p. 11). Draghi took a strong stance on this issue at a press conference earlier this year where he said: “We are hearing more and more complaints from Paris about the strength of the euro. Would you like to respond to them at all?”Likewise Coeuré (2014) responded in an interview with le Mode to French calls for euro devaluation: “There is a particular fascination with the exchange rate in France that is not shared by other euro area countries. No doubt this has something to do with the fact that France is one of the only countries in the euro area whose external accounts are in the red. However, the euro area as a whole is running a current account surplus: the solution for France, therefore, is to improve its competitiveness”.

This “case study” displaysonly a small part of a more general legitimacy and equal representation problem. As highlighted by Belke et al. (2004), “industry representatives ... often speak out in favour of a devaluation policy probably because they expect a group-specific net gain from this devaluation. By this, the determination of exchange rates and thus also, a significant part of the exchange rate variance comes under the influence of political-economic considerations”.

Global currency wars

The Fed, the BoE and the Bank of Japan have been the target of critics who have argued that the primary aim of their quantitative easing(QE) policies is the weakening of their respective exchange rates. In 2010, Stiglitz branded the Fed’s QE policy as a “beggar-thy-neighbour” strategy of currency devaluation: “President Obama has rightly said that the whole world will benefit if the U.S. grows, but what he forgot to mention is…that competitive devaluation is a form of growth that comes at the expense of others... So I think it is likely to present problems for the global economy going forward” (Frangos, 2010).Indeed, strong money outflows from advanced economies looking for higher yields in emerging markets have caused serious financial stability concerns in the latter, which were maybe articulated most prominently by Brazil’s president Dilma Rousseff, who in March 2012 complained about the “monetary tsunami” that was making its way to emerging economies (Volz, 2012).

As noted by Bénassy-Quéré et al. (2014), conflicts may arise when all countries seek to depreciate (or appreciate) their currency at the same time. While concerted efforts by the ECB to devalue the euro could indeed contribute to a “currency war” with competitive devaluations, it should be noted that the ECB has been the only among the major central banks that has thus far refrained from actively debasing its currency. Not only have the Fed, the BoE and the BOJ all openly tried to devalue their currencies, all major emerging market central banks have for long managed exchange rates in order for their economies to remain “competitive”. In East Asia in particular, China and other countries of the region have maintained “competitive” exchange rates under the “East Asian dollar standard”. Although East Asian economies have weathered the Global Financial

Crisis much better that the Eurozone, their willingness to appreciate their currencies even in when their economies were facing the danger of overheating was limited. Since a resolution of the European debt problems and a sustained recovery of the Eurozone is also in the interest of the rest of the world, as this would ultimately boost the Eurozone’s imports volume from the rest of the world again and reduce financial contagion risk, a modest euro devaluation should not lead to a competitive devaluation spiral.

Draghi (2014b) has brushed aside concerns that QE or other policies adopted by the ECB may cause irritation elsewhere:”You know that there is a G-20 statement that says that exchange rate matters are matters of common concern. And so we will have to reflect on this and see. But in our case, certainly, they have an impact on our objective of price stability, and especially, as I said, at this low level of inflation.”

A strong euro has been a worry for many. For the ECB, it is a concern to the extent that exchange rate appreciation has had a negative impact on import prices and thereby contributed to inflation rates much below the ECB’s target range. A strong exchange rate has also been a concern for policymakers, especially in the European crisis economies which have been suffering from a lack of competitiveness, as it has strained European exporters and dampened growth. Moreover, by contributing to lower inflation and suppressing (export) growth, a strong euro may impede and slow the resolution of European debt problems as low inflation keeps real interest rates high and slow growth lessens debtors’ repayment capacity.

For sure, a devaluation strategy is no panacea to the Eurozone’s problems. Macroeconomic imbalances within the Eurozone need to be resolved primarily by structural adjustments. However, a modest euro devaluation and higher inflation in the core countries will facilitate adjustments in the periphery countries. In conjunction with higher wage rises in Germany—as recently proposed by the Bundesbank (2014)—a weaker euro would diminish the need for nominal wage cuts in the periphery countries so that real adjustment there can process less painfully and more smoothly. At the same time, competitiveness of the German economy vis-à-vis the rest of the world would be unchanged as higher wage growth would be compensated by a weaker euro. Given that a recovery of the Eurozone is also in the interest of emerging economies, claims about ‘unfair devaluations’ are not apt.

Belke, A. H. (2014). The strength of the Euro – Challenges for ECB monetary policy.Directorate General for Internal Policies. Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy.

Belke, A. H., Göcke, M., & Günther, M. (2013). Exchange rate bands of inaction and play-hysteresis in German exports–Sectoral evidence for some OECD destinations.Metroeconomica, 64(1), 152–179.

Belke, A. H., & Gros, D. (2014, April 24). Kontraproduktive unkonventionelle Geldpolitik? oder: Wie das Gespenst der Deflation nicht zu vertreiben ist. Retrieved from the Ökonomenstimme website: http://www.oekonomenstimme.org/artikel/2014/04/kontraproduktive-unkonventionelle-geldpolitik-oder-wie-das-gespenst-der-deflation-nicht-zu-vertreiben-ist/

Belke, A. H., Herz, B., & Vogel, L. (2006). Beyond Trade – Is Reform Effort Affected by the Exchange Rate Regime? A Panel Analysis for the World versus OECD Countries.ÉconomieInternationale, 107, 29–58.

Belke, A. H., Kösters, W., Leschke, M., & Polleit, T. (2004). Liquidity on the rise - Too much money chasing too few goods. ECBObserver, 6, 9–15.

Bénassy-Quéré, A., Gourinchas, P. O., Martin, P., & Plantin, G. (2014).The Euro in the ‘Currency War.Les notes du conseild’analyseéconomique, 11.

Bernanke, B. S. (2003, May 31). Some Thoughts on Monetary Policy in Japan. Retrieved from the Federal Reserve website:www.federalreserve.gov/BoardDocs/Speeches/2003/20030531/

Buell, T., & Lawton, C. (2014, April 9). ECB’s Bonnici Says Bank Will Take Rising Euro Into Account. Wall Street Journal.

Bundesbank. (2014, July 31). President Weidmann puts the Bundesbank’s position in the wage debate into perspective. Retrieved from the Bundesbank website: www.bundesbank.de/Redaktion/EN/Topics/2014/2014_07_31_president_weidmann_puts_the_bundesbank_position_in_the_wage_debate_into_perspective.html

Buttonwood. (2011, June 14). Escaping the debt crisis. The inflation option. Retrieved from The Economist website:www.economist.com/blogs/buttonwood/2011/06/escaping-debt-crisis

Chinn, M., & Frieden, J. (2011).Better Living Through Inflation. The Milken Institute Review, Third Quarter 2012, 5–11.

Coeuré, B. (2014, April 17). Interview of Le Monde with Benoît Coeuré, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB. Retrieved from the European Central Bank website: www.ecb.europa.eu/press/inter/date/2014/html/sp140422.en.html

Draghi, M. (2012, July 26).Speech by Mario Draghi at the Global Investment Conference in London. Retrieved from the European Central Bank website:www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2012/html/sp120726.en.html

Draghi, M. (2013, July 4). Introductory statement to the press conference (with Q&A).Retrieved from the European Central Bank website: www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/2013/html/is130704.en.html

Draghi, M. (2014, March 13). Bank restructuring and the economic recovery. Retrieved from the European Central Bank website: www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2014/html/sp140313_1.en.html

Draghi, M. (2014, May 8). Introductory statement to the press conference (with Q&A). Retrieved from the European Central Bank website: www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/2014/html/is140508.en.html#qa

Draghi, M. (2014, May 26). Monetary policy in a prolonged period of low inflation. Retrieved from the European Central Bank website: www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2014/html/sp140526.en.html

Draghi, M. (2014, June 5). Introductory statement to the press conference (with Q&A).Retrieved from the European Central Bank website:www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/2014/html/is140605.en.html

Draghi, M. (2014, July 14). Introductory statement by Mario Draghi. Retrieved from the European Central Bank website:www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2014/html/sp140714.en.html

Draghi, M. (2014, August 7). Introductory statement to the press conference (with Q&A).Retrieved from the European Central Bank website: www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/2014/html/is140807.en.html

Frangos, A. (2010, November 11). Stiglitz to Obama: You’re Mistaken on Quantitative Easing. Retrieved from the Wall Street Journal website:http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2010/11/11/stiglitz-to-obama-youre-mistaken-on-quantitative-easing/

Gros, D., Alcidi, C., Belke, A. H., Coutinho, L., & Giovannini, A. (2014).State-of-play in implementing macroeconomic adjustment programmes in the Eurozone. Directorate General for Internal Policies. Economic Governance Support Unit.

Imbs, J., & Méjea, I. (2010).Trade Elasticities. A Final Report for the European Commission. Economic and Financial Affairs. Economic Paper No. 43.

Jolly, D., Alderman, L., & Bray, C. (2014, June 7). Five experts evaluate E.C.B.’s policy shift. New York Times.

Krugman, P. R., Obstfeld, M., & Melitz, J. (2012).International Economics – Theory & Policy. 9th ed. Boston et al.: Pearson.

Volz, U. (ed., 2012). Financial Stability in Emerging Markets – Dealing with Global Liquidity. Bonn: German Development Institute.

Volz, U. (2013). Lessons of the European Crisis for Regional Monetary and Financial Integration in East Asia. Asia Europe Journal, 11(4).355–376.

Last Update: 24/12/2021