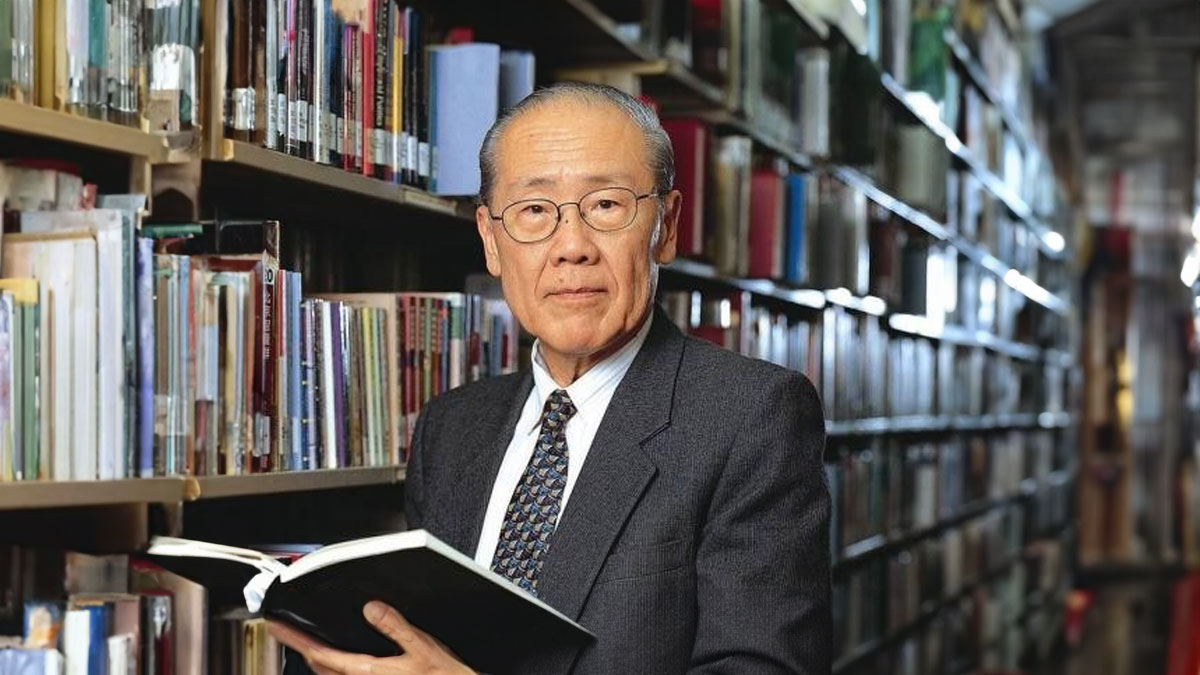

Today the discipline of International Relations (IR) has reached an impasse. Its neglect of cultural and historical knowledge can no longer be sustained. As the world moves beyond the American era, it is increasingly important to examine the behaviour of a range of influential countries – and in some cases this behaviour is perplexing. Thankfully, as will be discussed below, there is at last a dawning recognition in IR of the need for dialogue with ‘area studies’ (in particular, the study of history and political culture). Over a long period, Wang Gungwu has been prominent in expressing frustration about IR’s resistance to non-Western perspectives – and his own writing provides a model of how area knowledge can be harnessed to the analysis of inter-state relations.

One indication of the current crisis for IR is the complaints made by a number of practitioners – senior officials responsible for the practical management of foreign relations. Bilahari Kausikan, former Permanent Secretary at Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, has said that he found IR unhelpful in his career; as it is “too mechanical, gives insufficient weight to human agency, and is often based on premises that are irrelevant to Singapore’s specific circumstances”. For Bilahari, the “study of history, literature and philosophy” seemed to be “better preparation for understanding international affairs…” (Kausikan 2017). This view was supported recently by the Malaysian Ambassador to China, Raja Nushirwan, who described IR theory as “very much Western- oriented” and suggested it might be best to “study literature” if “you want to effectively manage relations between countries” (Nushirwan 2019).

Culture and history – area knowledge – has certainly been neglected by IR specialists. Pinar Bilgin has complained that IR students ‘have not been socialised” to become “curious about the ‘non-West’”; rather they have been encouraged to “explain away ‘non-Western’ dynamics by superimposing ‘Western’ categories”. The non-West, she added, was likely to be represented as “part of an ostensibly ‘universal’ story told in and about the ‘West’” (Bilgin 2008: 11-12). The IR group which has probably taken historical context most seriously and might have been expected to take an interest in non-Western perspectives, is the so-called ‘English School’. Hedley Bull certainly expressed a degree of anxiety about the Western bias of IR scholarship and asked whether there was “a significant body of non-Western theory” that had been “overlooked because of our Western starting point” (Bull 1977: 55). In general, however, even English School analysts have tended (until recently) to give little attention to Asian and other non-Western cultures – assuming, in Hidemi Suganami’s words, that “western civilisation” offered what was necessary to “assess the progress of human history” (Suganami 2003: 265). To take a final example, the Oxford Handbook of International Theory – co-edited by the Constructivist IR specialist, Chris Reus-Smit – has only one reference to culture in its lengthy subject index (Reus-Smit & Snidal 2010).2

A strong view in IR – stated succinctly by Kenneth Waltz – is that “states similarly placed behave similarly despite their internal differences” (Waltz 1996: 54). That is to say, states behave as states and the role of culture and history, as a result, is not a significant consideration. Furthermore, the way states interact seems always to be understood as governed by their concern for sovereignty and the operations of power, including the quest for a balance of power (Alagappa 2003: 86; Chin & Suryadinata 2005: 141; Haacke 2006: chapter 4). Some states, of course, rise while others fall – and IR specialists have been developing the ‘Power Transition Theory’, identifying the causes of power shifts and the points at which the probability of war is highest. The rise of China, in this view, needs to be examined with reference to the rise of Germany (in the 19th century) or of Athens (in the period leading up to the 5th century BC Peloponnesian War) (Allison 2017: 80-82). It is not the ‘internal differences’ between these contending states that demand attention in this type of analysis, but the patterns of interaction that are likely to develop when any hegemon is declining in relative terms.

I will consider Wang Gungwu’s response to this point of view at a later point. What needs to be stressed here is the context in which cultural factors have been given little weight. The two decades from the 1990s into this century were a time when it seemed relatively easy to dismiss area knowledge – but the situation is now transformed. In the years immediately following the Cold War, many believed in a coming convergence of ideas as well as economies; no ideology in this era of apparent globalisation seemed capable of competing with Western liberal thought. Former Governor of Hong Kong, Chris Patten, believed that nothing could stop the progress of Western ideas. “You cannot compartmentalise freedom,” he argued, you “may build walls between economics and politics, but they are walls of sand” (Patten 1998: 181). Influential Australian Foreign Minister, Gareth Evans, predicted English would continue to spread as a lingua franca in the Asian region and that the coming cultural convergence would be based on liberal principles such as multiculturalism and democracy (Evans 1995: 106-107).

In these years, the concept of culture itself came under increasing attack. To stress the role of culture was often seen as essentialism and an attempt to deny change. Leading cultural anthropologist Clifford Geertz complained that questions “rained down” on the “very idea of a cultural scheme” – questions about the homogeneity of cultures, about the “possibility of specifying where one culture … leaves off and the next …begins”, about “continuity and change”, “determinism and relativism”, and so forth (Geertz 1995: 42-43). The tone in which ‘culture’ was dismissed is reminiscent of French Enlightenment thinking. The triumphant Western analyst – to paraphrase Louis Dumont – identified “his own particular culture with ‘civilisation’, or universal culture. At bottom, he [did] not acknowledge the existence of cultures different from his own” (Dumont 1994: 3). In the intellectual climate of the 1990s, it is not surprising, as Pinar Bilgin observed, that IR students were not encouraged to explore area studies.

Beyond America and Europe, this culture-blind IR was often met not with resistance but submission. In the Asian region, many academic analysts accepted Western methodology and epistemology in both IR and other branches of social science. To this day, university IR departments in Asian countries are likely to teach and endorse a structure of analysis developed in the West – particularly the United States and the United Kingdom. This said, there were indications even in the 1990s of discomfort with this Western hegemony. There were complaints about the “self-congratulatory” tone of much Western analysis and the “current triumphalism of Western values” (Bilahari Kausikan, quoted in Huntington 1993: 193). Political leaders (particularly Prime Ministers Mahathir of Malaysia and Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore) and think tank analysts dared to suggest that ‘Asian values’ might have had a role in promoting the economic development their countries were enjoying. They claimed that rather than merely accepting the dictates of Western liberal universalism, it was critical to take into account Asian social values. Even the definition of human rights – so participants at a 1993 conference in Bangkok argued – needed to acknowledge Asian perspectives, including the preferred primacy of economic rights over civil and political rights. Although many cases were advocated with passion, such ‘Asian’ advocacy often met with ridicule in the West – or with the accusation that ‘Asian values’ were deliberately enunciated only to justify illiberal forms of government (Milner 2000). When the Asian economic crisis struck in 1997, some Western commentators were triumphant, one (Francis Fukuyama) claiming that it had “puncture[d] the idea of Asian exceptionalism” (Milner 2000: 58). Today, following the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, and growing prosperity in Asia, the case against ‘Asian values’ is far weaker.

The dominant trend of the 1990s, therefore, was clear – but more needs to be said about the dissenting academic voices, including that of Wang Gungwu. The leading military historian and strategic analyst, Michael Howard, responded by insisting on a distinction between interstate and international relations. International relations, he wrote in 1991, meant “dealing with foreigners”. A problem with many textbooks on IR was that they treated states as ‘entities to be assessed in quantifiable or behavioural terms as economic potential, military power, technological development, internal political structure or geopolitical imperatives’. Such an approach, ironically, was ‘the product of a political culture’ – the product, that is, of ‘Anglo-Saxon political thought’. In Howard’s view, “the first duty of the theorist and of the practitioner of IR” ought to be “empathy: the capacity to enter into other minds and understand other ideologies formed by environment, history and education in a very different mould from our own”. To achieve this empathy, he argued, required the study of foreign languages “which both express and create these differences between nations”. A second way of understanding “other peoples and their ideologies”, Howard pointed out, was through the study of history – a pursuit that “enables us to understand ourselves as well as other cultures” (Howard 1991: 150-151).

In anthropology, where the focus on culture has been sharpest, the fact of cultural complexity and change in most societies was acknowledged (Ortner 1999) – but there were still in some quarters determined advocates of the analytic significance of culture. Clifford Geertz argued (in 1995) that “no one who comes to Morocco or Indonesia to find out what goes on there is likely to confuse them with each other or to be satisfied with elevated banalities about common humanity or a universal need for self-expression” (Geertz 1995: 23).3 These were challenging words, but what provoked most reaction from IR specialists was a surprising culturalist line of argument from one of America’s leading political scientists. Samuel Huntington suggested that far from being irrelevant in a coming globalised era, the “dominating source of conflict” in the years ahead was likely to “be cultural” (Huntington 1993: 22). Discussing the Islamic world, it was by no means inevitable that Muslims would eventually be Westernised. He noted, in fact, the “inhospitable nature of Islamic culture and society to Western liberal concepts” (Huntington 1996: 14). Turning to China, “contemporary Sinic civilisation” was becoming structured in China’s historic style, with an “Inner Asian Zone” and an “Outer Zone” – the latter being tribute-bearing “barbarians” who had to acknowledge China’s superiority (Huntington 1996: 168).

This view of a world structured into Islamic, Chinese and other clashing civilisations attracted widespread criticism. Huntington’s stress on “civilisation rallying” (Huntington 1996: 272, 285), it was said, ignored other loyalties – including state loyalty – in international tension. He was also accused of underestimating the divisions within his so-called civilisations. In Stephen Walt’s words, “being part of some larger ‘civilisation’ did not convince Abkhaz, Armenians, Azeris, Chechens, Croats, Eritreans, Georgians, Kurds” and others to “abandon the quest for their own state, just as being part of the West did not slow Germany’s rush to reunify” (Walt 1997: 187). A further problem was the extent to which civilisations change – and have also influenced one another in profound ways. Finally, Huntington was attacked for making religion the key defining characteristic of a civilisation, when individuals in fact claim many types of identity (Cannadine 2013: 251-254).

A good deal of this criticism was well-founded, but it concentrated on culture as the focus of identity and loyalty – on ‘civilisation rallying’. A second dimension of culture which received less attention in Huntington’s writing was culture as the “meaningful structures” or categories of understanding and experience which shape human behaviour. These are the elements of operational equipment which Clifford Geertz’s writing examined with such care (Geertz 1975: 364). There is likely to be continued discussion about whether the world faced a ‘clash of civilisations’, but what is of most importance to IR analysis today is Huntington’s discussion of these cultural specificities (as they might be termed).

When non-Western societies “felt weak in relation to the West”, so Huntington explained, they appropriated Western ways of thinking (Huntington 1996: 93). With the erosion of European and American power, however, “indigenous, historically rooted mores, languages, beliefs, and institutions reassert themselves” (Huntington 1996: 91). Some Islamic perspectives, of course, directly challenge dominant Western cultural perspectives in one area after another – resisting the secular world view, for instance, by highlighting religious motivation and refusing to accept man-made state sovereignty as an alternative to divine authority (Huntington 1996:109-120; see also, Shahrbanou Tadjbakhs 2010: 88). In China and some other East Asian societies, Huntington noted a “shared rejection of individualism and the prevalence of ‘soft’ authoritarianism or very limited forms of democracy” (Huntington 1996: 108). The Chinese leadership, he suggested, had an idiosyncratic view of the state – perceiving “mainland China as the core state of a Chinese civilisation toward which all other Chinese communities should orient themselves” (Huntington 1996: 169). To take another example, the heritage of hierarchical thinking in “Chinese civilisational identity” tended to make China unsympathetic to multipolar concepts of security; also, it helped to explain why the “functioning balance of power system” (which was ”typical of Europe historically” and fundamental in Western IR theory) was “foreign to Asia” (Huntington 1996: 231-234). Huntington was not a China specialist but he was raising profound questions about the type of assumptions which tended to underpin IR analysis.

One commentator who saw the analytic benefits for IR in Huntington’s stress on cultural specificities was Wang Gungwu. He was unusual in responding positively to Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations – and his review is a useful starting point for examining the contribution Wang himself has made to the struggle against a culture-blind IR.

Wang believed Huntington had focused on ‘civilisations’ because he wanted to emphasise “the increasing inadequacy of Eurocentric models of international politics in the contemporary world” (Wang 1996-1997: 69). Huntington’s intention, said Wang, was to bury the “Western utopian ideal” of a “single universal civilisation that would ultimately absorb all other civilisations” (70). Huntington, in fact, was “admirably frank about the decline of the West” and thus offered a “major corrective to the complacency and arrogance that have dominated Western self- perception for the past century and a half” (71). Huntington was arguing that the “globalised universalism in the Western way of thinking about global issues” had now to give way (69).

Wang suggested that if Western thinking is less than universal – as Huntington argued – then there would have to be a “revolution of attitudes”. A “new language and vocabulary” would need to be developed (71). The actions of the key protagonists in the international arena, said Wang, might now be analysed in terms of “a new logic and language of behaviour.” Like Machiavelli in the 16th century, Huntington was offering a “new paradigm” for understanding “the real world” (73).

It has been observed that Wang has “never made the case for a distinctively or exclusively Chinese theory of IR” (Evans 2010: 54). When we read what Wang Gungwu himself has written and said in various contexts, however, it is clear how strongly he has been yearning for a ‘new logic’. In an extended interview published in 2015, he complained that “the whole language of IR is such that anybody in Asia studying IR will attain an Anglo-American world view. There is no way you can get out of it” (Ooi 2015: 88).4 The English language itself “carries its own rationale” (Ooi 2015: 187). In the case of China, Wang noted that “when the Chinese situation does not fit the theory, the language somehow puts the Chinese either as the villain, or as the weak, the subordinate or whatever…” (189). He related the experience of the prominent Chinese scholar, Yan Xuetong, who studied at Berkeley but found what he learnt did not “match the reality that China faces”. The “language” did not “describe the situation” and was “actually framed for some other power situation” (187–188). Faced with this problem, explained Wang, Yan turned to Chinese history to find a more authentic language for explaining China’s behaviour (Yan 2013).

It is not just IR, but social science in general which has caused Wang’s concern. The “assumptions underlying the inquiries of social scientists in, say America, about the way society is or should be organised, how their people generalise their wants and desires” and so forth “are based on certain ways of doing things that are common in the West, and highly developed and particularised”. The problem is that the “kind of society” from which the social scientist “drew those results may never have existed in China.” When such a researcher insists on this methodology, the danger is that he or she will try to “force the results to conform by making adjustments, tweaking a little here and there” – and then the “social science professors can say, ‘Oh, good, it works’” (Wang 2010: 156-157). Whether dealing with China, Islamic societies or other parts of the non-Western world, Wang has drawn the conclusion that “the deep roots of political culture are very important problems for the social sciences” (153).

Wang has employed historical and cultural insights to suggest numerous ways in which – particularly in Western terms – Chinese approaches are distinctive. For the Chinese, for instance, the “idea that the individual is 324 sacred” (and even more important than the family and community) is “beyond comprehension”. In China, you are “a great individual because you have your family behind you”. Real individualism “only comes from monotheistic religions”– which set the family aside and focuses on the relation between the individual and God (Ooi 2015: 204–205). There is also a particular Chinese understanding of ‘soft power’. In the West, it is concerned essentially with “cultural values, ideas, principles, dreams; the humanistic side of things”. Reading Chinese writings on soft power, they “all talk about business” – about economic power (173–174). As to how law is understood, the Chinese “do not have this idea that the law is sacred … to them it is just an instrument” (154). They “find it very strange” when they are criticised with such words as “this is the rule, you’re not observing it”. The idea that “once you have an agreement, it is forever” has “never been a part of Chinese culture” (155).

Specific Chinese thinking about the character of the state has been a strong concern for Wang, including in his most recent book: China Reconnects (Wang 2019). The top-down, centralised structure of the Chinese state contrasts, for instance, with India’s long experience of a loosely structured state, where different parts of India “operate almost independent of each other”. India’s “whole cultural heritage is not susceptible to revolutionary change”. In China, suggests Wang, revolution was successful “because it was centrally-based”, allowing for “top-down revolutionary change” (132–133). The relationship between state and business in China, he has pointed out, is also revealing. Chinese economic growth has “always depended on the central government, and when the central government did not emphasise trade and treated traders badly instead, the economy became agrarian and stagnant” (130). Even today, a Chinese entrepreneur, “however private he may have started out being, knows that he has to work very closely with the high official (Guan)” (180). Finally, as to the relation between state and religion, Wang has suggested that the Chinese have never had the separation of the two – and he explains this in terms of the particular role of Confucianism (28–29).

In these and other areas China is distinctive and, contrary to Waltz’s downplaying of the relevance of ‘internal differences’ between states, this distinctiveness – in Wang’s analysis - is an issue in China’s international relations. China can worry people in the West, says Wang, because China offers “an alternative” – even India is an “extension of the Anglo-American world” (10-11). If it happens that “the Chinese become more successful in administering the state” it is possible that “people will begin to have doubts about the Anglo-American global system” (42).

With respect to IR, what Wang has been especially wary of is false historical analogies. He cites President Nixon’s determination to draw a parallel between Ho Chi Minh and Hitler – insisting in the case of Vietnam that “we’ve had this kind of experience before. We mustn’t allow any more ‘Munichs’” (189). The important misleading analogy today is the effort to treat China as if it is 20th century Germany or Japan – imposing a “universal rule” that a “rising power” is a “danger to the status quo” and “must be watched and stopped” (190). It is difficult for the Chinese to reply to this, Wang points out, because they “don’t have a theoretical field to counteract it” (190). Developing such a theoretical field, as Wang notes, is a task Yan Xuetong has set himself.

Time and again Wang has sought to add historical and cultural knowledge to IR analysis. Back in the 1970s he took the approach of insisting on the distinction between expansionism and the “fervent desire for independence” as a national objective (Wang 1977: 140). China , he argued, saw “most of the world as manipulated and dominated by a few strong and rich powers” – and not only sought “its own complete independence” but also wanted to set “an example to all others who [were] much less independent than it [was]” (140). The idea of becoming a “Super Power”, Wang suggested, was not attractive to China because it was “associated with dominance and ‘hegemonism’, with their echoes of traditional imperialism …” (138). In more recent years, Wang has harnessed pre-modern historical knowledge to counter accusations that China will be expansionist. In certain periods, he says, China has had “the power to dominate others” but was restrained. The contrast with some Western countries is striking – and, of course, has been noted by others in the Asian region in recent times. (Jalpragas 2017). The “Mediterranean political consciousness”, Wang notes, is “based on competition, rivalry and fighting each other to a standstill”. China, on the other hand, has been influenced by “Confucian ideology” which “insisted on not pushing beyond frontiers, on the very realistic and practical grounds that if you can’t control something, don’t take it”. In this Confucian view, you give “order and provide civilisation” but “don’t bother with people whom you can’t control and are not like you” (Wang 2010:100).

The Chinese, says Wang, do not have a record of imperial expansion. The “idea of setting out to colonise somebody else’s territories … never occurred to the Chinese” (95). The second Ming emperor sent immensely powerful naval expeditions into the wider world in the 15th century – led by Zheng He – but the expeditions were then cancelled “in favour of expenditure on continental defence instead” (Ooi 2015: 231, 66; Wang 2010: 174). This preference continues to be of importance today. Many commentators on the Asian region have pointed to China’s current naval build-up, particularly in the South China Sea, and history has shown the Chinese that they are vulnerable to attack from the sea. Nevertheless, Wang has argued that the Chinese are “essentially not a maritime force”. They “don’t think in maritime terms” and the navy “will always be a minor force in China” (Ooi 2015: 185, 163–167).

Regarding expansionism, it is true that after the Chinese inherited the Manchu Qing empire in 1911, they proposed to protect it “as their own”. Some scholars, says Wang, want to call this imperialism, “but it was something quite different from what the West did when it sent people to the Americas, Australia and New Zealand, or when it seized territories in Asia and Africa” (Wang 2010: 97). The phrase ‘world order’, suggests Wang, can add to confusion. The concept “is a Western one”. The Chinese historically did “have an idea of order that was hierarchical, one in which they saw themselves as the most civilised and developed”. But the Chinese view “was not a concept of world order that led them to justify any kind of military intervention or the expansion of Chinese territory” (99). In his most recent book, Wang suggests that China today is not challenging the U.S. but merely wanting to safeguard China’s “development” - to ensure that China is not “dictated to in the name of a ‘final’ world order that all countries must always accept” (Wang 2019: 123). Here again is the ‘independence’ aspiration which Wang explained in the 1970s.

It is possible that the future China, says Wang, could be influenced by different, foreign models. Japan “got carried away by the power of the Western national model. It thought it could do the same and invaded China and Southeast Asia”. The Chinese, Wang predicts, are unlikely to follow this path: they are “studying all this and realising that it is not part of their tradition” (Wang 2010: 98). What causes Wang anxiety is the way some analysts “read back the kind of imperialist model that has come from the West into Chinese experience” (95). Not just in recent times but over many decades, he has insisted that knowledge of the Chinese heritage is critical when speculating on China’s future international role – and that the Chinese themselves will probe that heritage as they plan the way forward.5 This is not to be understood as insistence on an ‘unchanging China’. Indeed, he has stressed that the Chinese have a deep- rooted assumption about the “prevalence and inevitability of change” (quoted in Zheng 2014: 310; Wang 2019: xix, 24-25, 48, 61, 76, 121–122).

Wang, in his way, has been no less troubled by mainstream IR analysis than the two official diplomatic practitioners – Bilahari Kausikan and Raja Nushirwan – cited above. Time and again, he has probed Chinese history and political culture to warn commentators in IR against the assumption that ‘states similarly placed behave similarly’. When we take into account the specific character of the Chinese state – in addition to the heritage of its pre-modern approaches to foreign relations – it also seems unhelpful to define China merely as a ‘rising power’. Doing so obscures the specific ambitions and anxieties which make China different from other states (including within Asia) – and which are likely to determine the way in which China might rise. The tendency to attribute Western- style balance of power thinking to China is yet one more way in which IR analysis may be distorting, particularly by sidelining the long tradition of hierarchical diplomacy in the Asian region. ‘State’, ‘sovereignty’, ‘balance of power’, ‘rising power’ – these are all key IR terms which, following Wang’s analyses, require careful interrogation.

The comments above focus most on China, but Wang and others have also been drawing on area knowledge in their analyses of India and Southeast Asian foreign relations.6 To finish this essay on an optimistic note – as suggested in my opening paragraph, today there is finally growing support for cooperation between IR and area specialists. The developing interest in ‘non-Western IR theory’ (Acharya & Buzan 2010) is critical here. A small group within IR has been acknowledging the need to comprehend the “dynamics of power and ideas” that may be “fundamentally different” from those grounded in the familiar so-called Westphalian model (Acharya 2014: 652).7 It is admitted that “key IR concepts, including the state, self-help, power, and security” – concepts developed in Western contexts – may not “fit” non-Western realities (Waever & Tickner 2009, 1). A related development is that some members of the history-minded English School in IR are now investigating not just European, but non-Western narratives and perspectives (Buzan 2014: 169). Barry Buzan, for instance, has been working with Chinese scholars, examining (as Wang Gungwu and Yan Xuetong have done) concepts employed in pre-modern China’s international relations (Zhang & Buzan 2012; Wang & Buzan 2014).

As a leader in the study of non-Western IR, Amitav Acharya has called for a genuinely “global IR” that is “more authentically grounded in world history” – a new IR that will look beyond “national interest and distribution of power”, and so forth, and pay attention to “other sources of agency, including culture, ideas and norms” (Acharya 2014: 650). He writes of the necessity to investigate “distinct and diverse cultural and historical experiences that inform their conceptions of and approach to world order” (653) – and sees this as an interdisciplinary project. There must be “convergence and synergy” in particular between IR and “area studies”, the latter (in Acharya’s view) offering “empirical richness” and a “strong emphasis on field research” (655, 650).

These words are promising. With the global distribution of power moving away from the United States and Europe – and the relative prosperity of Asia vis-a-vis the West much enhanced – the damage done to IR by its neglect of area knowledge has become more and more obvious. In this essay, I have suggested ways in which Wang Gungwu over many years has been seeking the required ‘synergy’. He has provided a model in harnessing historical (and political culture) knowledge to the analysis of international dynamics. Some scholars will debate Wang’s assessments but if we wish to promote the interdisciplinary collaboration which Acharya seeks, the work of Wang Gungwu – and those following in his tradition – provides an ideal starting point.

1 Parts of this chapter draw upon Milner, 2017. I am grateful for advice from Astanah Abdul Aziz, Richard Higgott, Kwa Chong Guan, Peter Borschberg and Amitav Acharya – though I have not always taken their advice.

2 Reus-Smit, however, has now begun to focus on culture (Reus-Smit 2017). ‘Cultural Diversity and International Law’, International Organization, 71, Fall, 2017, 851-885

3 Geertz’s writing influenced the major project of the Academy of Social Sciences in Australia in the early 1990s – the Australia Asia Perceptions Project. Although running in the face of current theoretical fashion, the project examined the role of culture in strategic relations; see Milner and Quilty 1996: chapter 6.

4 Other writings by Wang on international relations include Wang and Zheng 2008; Wang 1999; and Wang 2019. For Wang’s writing in this area, see also Zheng 2014.

5 In 1968 Wang wrote an influential article on Ming dynasty relations with Southeast Asia, examining how those relations were structured. He concluded his essay with a discussion of modern China – arguing that as Communist China became more powerful, “it seems likely that the country will seek its future role by looking closely at its own history”: Wang 1981: 57.

6 For instance, Behera 2010; Saran 2017. With respect to Southeast Asia, see Raymond 2018; Chong 2012; Milner 2020; Milner and Munirah 2018. One influence on this writing is the Cornell (and later, Australian National University) emphasis on the study of political cultures – associated, for instance, with Oliver Wolters and Benedict Anderson. Amitav Acharya, in a wide range of publications, has focused over a long period on the heritage of foreign policy thinking in Southeast Asia.

7 See also, Higgott 2019, which includes essays by Amitav Acharya and Anthony Milner.

Acharya, Amitav and Barry Buzan. (eds.) (2010). Non-Western international relations theory. London, Routledge.

Acharya, Amitav. (2014). ”Global International Relations (IR) and Regional Worlds: A New Agenda for International Studies.” International Studies Quarterly, 58: 647–659

Alagappa, Muthiah. (ed.). (2003). Asian Security Order: Instrumental and Normative Features. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Allison, Graham. (2017). “The Thucydides Trap.” Foreign Policy, May/June.

Behera, Navnita Chaddha. (2010). “Reimagining IR in India.” In Amitav Acharya and Barry Buzan (eds) Non-Western International Relations Theory. London and New York: Routledge, 92-116.

Bilgin, P. (2008). “Thinking Past “Western” IR?” Third World Quarterly, 29 ,1: 5-23.

Bull, Hedley. (1977). The Anarchical Society. London: Macmillan, 1977.

Buzan, Barry. (2014). An introduction to the English School of international relations. Cambridge: Polity.

Cannadine, David (2013). The undivided past: History beyond our differences. London: Penguin.

Chin Kin Wah, and Leo Suryadinata. (eds.). (2005). Michael Leifer: Selected Works on Southeast Asia. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Chong, Alan. (2012). “Premodern Southeast Asia as a Guide to International Relations between Peoples: Prowess and Prestige in ‘Intersocietal Relations’’ in the Sejarah Melayu.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 37, 2: 87–105.

Dumont, Louis. (1994). German Ideology: from France to Germany and back. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Evans, Gareth. (1995). “Australia in East Asia and the Asia-Pacific: Beyond the Looking Glass.” Australian Journal of International Affairs, 49, 1: 99–113.

Evans, Paul. (2010). “Historians and Chinese World Order: Fairbank, Wang and the matter of ‘indeterminate relevance’.” In Zheng Yongnian (ed.). China and International Relations: the Chinese View and the Contribution of Wang Gungwu. London: Routledge: 62-77.

Geertz, Clifford. (1975). The interpretation of Cultures. London: Hutchinson.

Geertz, Clifford. (1995). After the Fact: Two Countries, Four Decades, One Anthropologist. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Haacke, Jurgen. (2006). “Michael Leifer, the balance of power and international relations theory.” In Joseph Chinyong Liow and Ralph Emmers (eds). Order and Security in Southeast Asia: Essays in memory of Michael Leifer. London and New York: Routledge: 68–82.

Higgott, Richard. (2019). Civilizations, States and World Order. Berlin: Dialogue of Civilizations Research Institute.

Huntington, Samuel P. (1993). “The Clash of Civilizations?” Foreign Affairs, 72: 63–70.

Huntington, Samuel P. (1996). The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Jalpragas, Bhavan. (2017). “Malaysia’s Mahathir Mohamad on why he’s not anti-China.” South China Morning Post, 1 April 2017: https://www.scmp. com/week-asia/politics/article/2083820/exclusive-malaysias-mahathir- mohamad-why-hes-not-anti-china

Kausikan, B. (2017). Dealing with an Ambiguous World. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2017.

Milner, Anthony. (2000). “What happened to ‘Asian Values’?” In Gerald Segal and David S. G. Goodman (eds.), Towards Recovery in Asia. London and New York: Routledge: 56–68.

Milner, Anthony. (2017). “Culture and the international relations of Asia.” The Pacific Review, 30, 6: 857–869.

Milner, Anthony. (2020). “Long-term themes in Malaysian Foreign Policy: Hierarchy diplomacy, non-interference and moral balance.” Asian Studies Review, 44: 1: 117–135.

Milner, Anthony and Mary Quilty. (eds.) (1996). Australia in Asia: Comparing Cultures. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Milner, Anthony and Munirah Kassim. (2018). “Beyond Sovereignty: Non-Western International Relations in Malaysia’s Foreign Relations.” Contemporary Southeast Asia, 40, 3: 371–396.

Nushirwan Zainal Abidin, Raja Dato. (2019). Keynote Speech, Asia Europe Conference, University of Malaya, 2019: https://aei.um.edu.my/keynote- speech-by-ym-raja-dato-rsquo-nushirwan-zainal-abidin-at-the-asia- europe-conference-2019.

Ooi Kee Beng. (2015). The Eurasian Core and its Edges: Dialogues with Wang Gungwu on the History of the World. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Ortner, Sherry S. (ed) (1999). The Fate of ‘Culture’: Geertz and Beyond. Berkeley: University of California Press).

Patten, Chris (1998). East and West. London: Macmillan.

Raymond, Gregory Vincent (2018). Thai Military Power: A Culture of Strategic Accommodation. Copenhagen: NIAS Press.

Reus-Smit, Chris and Duncan Snidal. (eds.). (2010). The Oxford Handbook of International Relations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Reus-Smit, Chris. (2017). “Cultural Diversity and International Law.” International Organization, 71, Fall: 851–885.

Saran, Shyam. (2017). How India sees the world: Kautilya to the 21st century. New Delhi: Juggernaut Books.

Suganami, Hidemi. (2003). “British Institutionalists, or the English School, 20 Years On.” International Relations, 17, 3: 253–272.

Tadjbakhs, Shahrbanou (2010). “International relations theory and the Islamic worldview.” In Amitav Acharya & Barry Buzan (eds.), Non-Western international relations theory. London: Routledge: 184–206.

Waever, Ole and Arlene B.Tickner. (eds.). (2009). International relations scholarship around the world. London: Routledge.

Walt, Stephen. (1997). “Building up new bogeymen.” Foreign Policy, 106: 177–189.

Waltz, Kenneth M. (1996). “International politics is not foreign policy.” Security Studies, 6,1: 54–57.

Wang Gungwu. (1981). “Early Ming relations with Southeast Asia – a background essay.” Reprinted in Wang Gungwu. Community and Nation: Essays on Southeast Asia and the Chinese. North Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Wang Gungwu. (1977). China and the World since 1949: The Impact of Independence, Modernity and Revolution. London and Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Wang Gungwu. (1999). China and Southeast Asia: Myths, threats and culture. Singapore and London: World Scientific and Singapore University Press.

Wang Gungwu. (1996-1997). “A Machiavelli for Our Times.” The National Interest, 46: 69–73.

Wang Gungwu and Zheng Yongnian. (2008). China and the new international order. London: Routledge.

Wang Gungwu. (2010). Junzi. Scholar-Gentleman. In Conversation with Asad-Ul Iqbal Latif. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Wang Gungwu. (2019). China Reconnects; Joining a Deep-rooted Past to a New World Order. Singapore: World Scientific.

Wang Jiangli and Barry Buzan. (2014). ‘’The English and Chinese Schools of International Relations: Comparisons and Lessons.” Chinese Journal of International Politics, 7: 1–46.

Yan Xuetong. (2013). Ancient Chinese Thought, Modern Chinese Power. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Zhang Yongjin and Barry Buzan. (2012). “The Tributary System as International Society in Theory and Practice.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics, 5: 3–36.

Zheng Yongnian. (2014). “Wang Gungwu and the Study of China’s International Relations.” In N. Horesh and E.Kavalski (eds.). Asian Thought on China’s Changing International Relations. London: Palgrave Macmillan: 54–75.

Last Update: 15/08/2024